problem

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution

stringlengths 3

10k

| answer

stringlengths 1

91

| problem_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | question_type

stringclasses 1

value | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 3

10k

| metadata

dict | uuid

stringlengths 36

36

| id

int64 22.6k

612k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

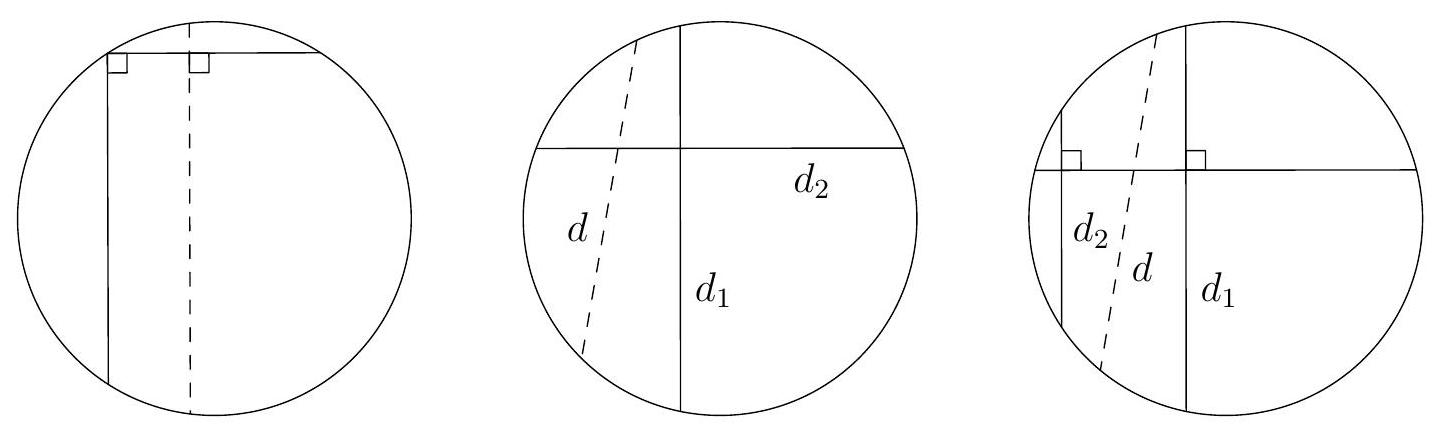

A regular 12-sided polygon is inscribed in a circle of radius 1. How many chords of the circle that join two of the vertices of the 12-gon have lengths whose squares are rational? (No proof is necessary.)

|

The chords joining vertices subtend minor arcs of $30^{\circ}, 60^{\circ}, 90^{\circ}, 120^{\circ}, 150^{\circ}$, or $180^{\circ}$. There are 12 chords of each of the first five kinds and 6 diameters. For a chord with central angle $\theta$, we can draw radii from the two endpoints of the chord to the center of the circle. By the law of cosines, the square of the length of the chord is $1+1-2 \cos \theta$, which is rational when $\theta$ is $60^{\circ}, 90^{\circ}, 120^{\circ}$, or $180^{\circ}$. The answer is thus $12+12+12+6=42$.

|

42

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A regular 12-sided polygon is inscribed in a circle of radius 1. How many chords of the circle that join two of the vertices of the 12-gon have lengths whose squares are rational? (No proof is necessary.)

|

The chords joining vertices subtend minor arcs of $30^{\circ}, 60^{\circ}, 90^{\circ}, 120^{\circ}, 150^{\circ}$, or $180^{\circ}$. There are 12 chords of each of the first five kinds and 6 diameters. For a chord with central angle $\theta$, we can draw radii from the two endpoints of the chord to the center of the circle. By the law of cosines, the square of the length of the chord is $1+1-2 \cos \theta$, which is rational when $\theta$ is $60^{\circ}, 90^{\circ}, 120^{\circ}$, or $180^{\circ}$. The answer is thus $12+12+12+6=42$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-92-2006-feb-team2-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n8. [25]",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

75c38285-e875-5238-b8be-6d16ff322e51

| 611,543

|

Find the largest positive integer $n$ such that $1!+2!+3!+\cdots+n$ ! is a perfect square. Prove that your answer is correct.

|

Clearly $1!+2!+3!=9$ works. For $n \geq 4$, we have

$$

1!+2!+3!+\cdots+n!\equiv 1!+2!+3!+4!\equiv 3 \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

but there are no squares congruent to 3 modulo 5 .

|

3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find the largest positive integer $n$ such that $1!+2!+3!+\cdots+n$ ! is a perfect square. Prove that your answer is correct.

|

Clearly $1!+2!+3!=9$ works. For $n \geq 4$, we have

$$

1!+2!+3!+\cdots+n!\equiv 1!+2!+3!+4!\equiv 3 \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

but there are no squares congruent to 3 modulo 5 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-92-2006-feb-team2-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n11. [15]",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

154c6346-7e13-5011-a284-1a849b0bb4fd

| 611,546

|

Four circles with radii $1,2,3$, and $r$ are externally tangent to one another. Compute $r$. (No proof is necessary.)

|

Let $A, B, C, P$ be the centers of the circles with radii $1,2,3$, and $r$, respectively. Then, $A B C$ is a 3-4-5 right triangle. Using the law of cosines in $\triangle P A B$ yields

$$

\cos \angle P A B=\frac{3^{2}+(1+r)^{2}-(2+r)^{2}}{2 \cdot 3 \cdot(1+r)}=\frac{3-r}{3(1+r)}

$$

Similarly,

$$

\cos \angle P A C=\frac{4^{2}+(1+r)^{2}-(3+r)^{2}}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot(1+r)}=\frac{2-r}{2(1+r)}

$$

We can now use the equation $(\cos \angle P A B)^{2}+(\cos \angle P A C)^{2}=1$, which yields $0=$ $23 r^{2}+132 r-36=(23 r-6)(r+6)$, or $r=6 / 23$.

|

\frac{6}{23}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Four circles with radii $1,2,3$, and $r$ are externally tangent to one another. Compute $r$. (No proof is necessary.)

|

Let $A, B, C, P$ be the centers of the circles with radii $1,2,3$, and $r$, respectively. Then, $A B C$ is a 3-4-5 right triangle. Using the law of cosines in $\triangle P A B$ yields

$$

\cos \angle P A B=\frac{3^{2}+(1+r)^{2}-(2+r)^{2}}{2 \cdot 3 \cdot(1+r)}=\frac{3-r}{3(1+r)}

$$

Similarly,

$$

\cos \angle P A C=\frac{4^{2}+(1+r)^{2}-(3+r)^{2}}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot(1+r)}=\frac{2-r}{2(1+r)}

$$

We can now use the equation $(\cos \angle P A B)^{2}+(\cos \angle P A C)^{2}=1$, which yields $0=$ $23 r^{2}+132 r-36=(23 r-6)(r+6)$, or $r=6 / 23$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-92-2006-feb-team2-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n13. [25]",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

576f643c-9e65-5481-aeeb-813251ca6922

| 611,548

|

Find the prime factorization of

$$

2006^{2} \cdot 2262-669^{2} \cdot 3599+1593^{2} \cdot 1337

$$

(No proof is necessary.)

|

Upon observing that $2262=669+1593,3599=1593+2006$, and $1337=$ $2006-669$, we are inspired to write $a=2006, b=669, c=-1593$. The expression in question then rewrites as $a^{2}(b-c)+b^{2}(c-a)+c^{2}(a-b)$. But, by experimenting in the general case (e.g. setting $a=b$ ), we find that this polynomial is zero when two of $a, b, c$ are equal. Immediately we see that it factors as $(b-a)(c-b)(a-c)$, so the original expression is a way of writing $(-1337) \cdot(-2262) \cdot(3599)$. Now, $1337=7 \cdot 191$, $2262=2 \cdot 3 \cdot 13 \cdot 29$, and $3599=60^{2}-1^{2}=59 \cdot 61$.

|

(-1337) \cdot(-2262) \cdot(3599)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find the prime factorization of

$$

2006^{2} \cdot 2262-669^{2} \cdot 3599+1593^{2} \cdot 1337

$$

(No proof is necessary.)

|

Upon observing that $2262=669+1593,3599=1593+2006$, and $1337=$ $2006-669$, we are inspired to write $a=2006, b=669, c=-1593$. The expression in question then rewrites as $a^{2}(b-c)+b^{2}(c-a)+c^{2}(a-b)$. But, by experimenting in the general case (e.g. setting $a=b$ ), we find that this polynomial is zero when two of $a, b, c$ are equal. Immediately we see that it factors as $(b-a)(c-b)(a-c)$, so the original expression is a way of writing $(-1337) \cdot(-2262) \cdot(3599)$. Now, $1337=7 \cdot 191$, $2262=2 \cdot 3 \cdot 13 \cdot 29$, and $3599=60^{2}-1^{2}=59 \cdot 61$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-92-2006-feb-team2-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n14. [40]",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

79f98328-6313-53b0-ac32-9c3a3e320303

| 611,549

|

Determine the smallest number $M$ such that the inequality $$ \left|a b\left(a^{2}-b^{2}\right)+b c\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)+c a\left(c^{2}-a^{2}\right)\right| \leq M\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{2} $$ holds for all real numbers $a, b, c$. (Ireland)

|

We first consider the cubic polynomial $$ P(t)=t b\left(t^{2}-b^{2}\right)+b c\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)+c t\left(c^{2}-t^{2}\right) . $$ It is easy to check that $P(b)=P(c)=P(-b-c)=0$, and therefore $$ P(t)=(b-c)(t-b)(t-c)(t+b+c), $$ since the cubic coefficient is $b-c$. The left-hand side of the proposed inequality can therefore be written in the form $$ \left|a b\left(a^{2}-b^{2}\right)+b c\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)+c a\left(c^{2}-a^{2}\right)\right|=|P(a)|=|(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| . $$ The problem comes down to finding the smallest number $M$ that satisfies the inequality $$ |(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| \leq M \cdot\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{2} \text {. } $$ Note that this expression is symmetric, and we can therefore assume $a \leq b \leq c$ without loss of generality. With this assumption, $$ |(a-b)(b-c)|=(b-a)(c-b) \leq\left(\frac{(b-a)+(c-b)}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{(c-a)^{2}}{4} $$ with equality if and only if $b-a=c-b$, i.e. $2 b=a+c$. Also $$ \left(\frac{(c-b)+(b-a)}{2}\right)^{2} \leq \frac{(c-b)^{2}+(b-a)^{2}}{2} $$ or equivalently, $$ 3(c-a)^{2} \leq 2 \cdot\left[(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}\right], $$ again with equality only for $2 b=a+c$. From (2) and (3) we get $$ \begin{aligned} & |(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| \\ \leq & \frac{1}{4} \cdot\left|(c-a)^{3}(a+b+c)\right| \\ = & \frac{1}{4} \cdot \sqrt{(c-a)^{6}(a+b+c)^{2}} \\ \leq & \frac{1}{4} \cdot \sqrt{\left(\frac{2 \cdot\left[(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}\right]}{3}\right)^{3} \cdot(a+b+c)^{2}} \\ = & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \cdot\left(\sqrt[4]{\left(\frac{(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}}{3}\right)^{3} \cdot(a+b+c)^{2}}\right)^{2} . \end{aligned} $$ By the weighted AM-GM inequality this estimate continues as follows: $$ \begin{aligned} & |(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| \\ \leq & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \cdot\left(\frac{(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}+(a+b+c)^{2}}{4}\right)^{2} \\ = & \frac{9 \sqrt{2}}{32} \cdot\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{2} . \end{aligned} $$ We see that the inequality (1) is satisfied for $M=\frac{9}{32} \sqrt{2}$, with equality if and only if $2 b=a+c$ and $$ \frac{(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}}{3}=(a+b+c)^{2} $$ Plugging $b=(a+c) / 2$ into the last equation, we bring it to the equivalent form $$ 2(c-a)^{2}=9(a+c)^{2} . $$ The conditions for equality can now be restated as $$ 2 b=a+c \quad \text { and } \quad(c-a)^{2}=18 b^{2} \text {. } $$ Setting $b=1$ yields $a=1-\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}$ and $c=1+\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}$. We see that $M=\frac{9}{32} \sqrt{2}$ is indeed the smallest constant satisfying the inequality, with equality for any triple $(a, b, c)$ proportional to $\left(1-\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}, 1,1+\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}\right)$, up to permutation. Comment. With the notation $x=b-a, y=c-b, z=a-c, s=a+b+c$ and $r^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}$, the inequality (1) becomes just $|s x y z| \leq M r^{4}$ (with suitable constraints on $s$ and $r$ ). The original asymmetric inequality turns into a standard symmetric one; from this point on the solution can be completed in many ways. One can e.g. use the fact that, for fixed values of $\sum x$ and $\sum x^{2}$, the product $x y z$ is a maximum/minimum only if some of $x, y, z$ are equal, thus reducing one degree of freedom, etc. As observed by the proposer, a specific attraction of the problem is that the maximum is attained at a point $(a, b, c)$ with all coordinates distinct.

|

\frac{9}{32} \sqrt{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Inequalities

|

Determine the smallest number $M$ such that the inequality $$ \left|a b\left(a^{2}-b^{2}\right)+b c\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)+c a\left(c^{2}-a^{2}\right)\right| \leq M\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{2} $$ holds for all real numbers $a, b, c$. (Ireland)

|

We first consider the cubic polynomial $$ P(t)=t b\left(t^{2}-b^{2}\right)+b c\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)+c t\left(c^{2}-t^{2}\right) . $$ It is easy to check that $P(b)=P(c)=P(-b-c)=0$, and therefore $$ P(t)=(b-c)(t-b)(t-c)(t+b+c), $$ since the cubic coefficient is $b-c$. The left-hand side of the proposed inequality can therefore be written in the form $$ \left|a b\left(a^{2}-b^{2}\right)+b c\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)+c a\left(c^{2}-a^{2}\right)\right|=|P(a)|=|(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| . $$ The problem comes down to finding the smallest number $M$ that satisfies the inequality $$ |(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| \leq M \cdot\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{2} \text {. } $$ Note that this expression is symmetric, and we can therefore assume $a \leq b \leq c$ without loss of generality. With this assumption, $$ |(a-b)(b-c)|=(b-a)(c-b) \leq\left(\frac{(b-a)+(c-b)}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{(c-a)^{2}}{4} $$ with equality if and only if $b-a=c-b$, i.e. $2 b=a+c$. Also $$ \left(\frac{(c-b)+(b-a)}{2}\right)^{2} \leq \frac{(c-b)^{2}+(b-a)^{2}}{2} $$ or equivalently, $$ 3(c-a)^{2} \leq 2 \cdot\left[(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}\right], $$ again with equality only for $2 b=a+c$. From (2) and (3) we get $$ \begin{aligned} & |(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| \\ \leq & \frac{1}{4} \cdot\left|(c-a)^{3}(a+b+c)\right| \\ = & \frac{1}{4} \cdot \sqrt{(c-a)^{6}(a+b+c)^{2}} \\ \leq & \frac{1}{4} \cdot \sqrt{\left(\frac{2 \cdot\left[(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}\right]}{3}\right)^{3} \cdot(a+b+c)^{2}} \\ = & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \cdot\left(\sqrt[4]{\left(\frac{(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}}{3}\right)^{3} \cdot(a+b+c)^{2}}\right)^{2} . \end{aligned} $$ By the weighted AM-GM inequality this estimate continues as follows: $$ \begin{aligned} & |(b-c)(a-b)(a-c)(a+b+c)| \\ \leq & \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \cdot\left(\frac{(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}+(a+b+c)^{2}}{4}\right)^{2} \\ = & \frac{9 \sqrt{2}}{32} \cdot\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{2} . \end{aligned} $$ We see that the inequality (1) is satisfied for $M=\frac{9}{32} \sqrt{2}$, with equality if and only if $2 b=a+c$ and $$ \frac{(b-a)^{2}+(c-b)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}}{3}=(a+b+c)^{2} $$ Plugging $b=(a+c) / 2$ into the last equation, we bring it to the equivalent form $$ 2(c-a)^{2}=9(a+c)^{2} . $$ The conditions for equality can now be restated as $$ 2 b=a+c \quad \text { and } \quad(c-a)^{2}=18 b^{2} \text {. } $$ Setting $b=1$ yields $a=1-\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}$ and $c=1+\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}$. We see that $M=\frac{9}{32} \sqrt{2}$ is indeed the smallest constant satisfying the inequality, with equality for any triple $(a, b, c)$ proportional to $\left(1-\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}, 1,1+\frac{3}{2} \sqrt{2}\right)$, up to permutation. Comment. With the notation $x=b-a, y=c-b, z=a-c, s=a+b+c$ and $r^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}$, the inequality (1) becomes just $|s x y z| \leq M r^{4}$ (with suitable constraints on $s$ and $r$ ). The original asymmetric inequality turns into a standard symmetric one; from this point on the solution can be completed in many ways. One can e.g. use the fact that, for fixed values of $\sum x$ and $\sum x^{2}$, the product $x y z$ is a maximum/minimum only if some of $x, y, z$ are equal, thus reducing one degree of freedom, etc. As observed by the proposer, a specific attraction of the problem is that the maximum is attained at a point $(a, b, c)$ with all coordinates distinct.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2006SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

ada6190f-c3c7-5d2c-b5e3-6a67a926cb07

| 23,542

|

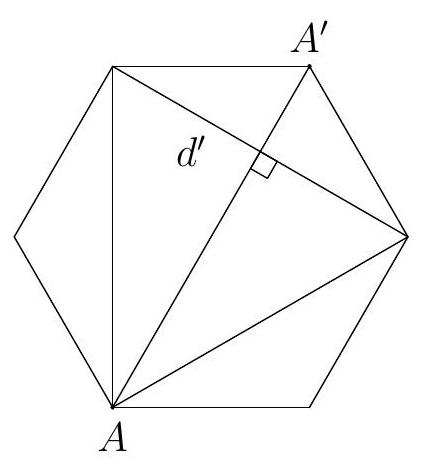

A diagonal of a regular 2006-gon is called odd if its endpoints divide the boundary into two parts, each composed of an odd number of sides. Sides are also regarded as odd diagonals. Suppose the 2006-gon has been dissected into triangles by 2003 nonintersecting diagonals. Find the maximum possible number of isosceles triangles with two odd sides. (Serbia)

|

Call an isosceles triangle odd if it has two odd sides. Suppose we are given a dissection as in the problem statement. A triangle in the dissection which is odd and isosceles will be called iso-odd for brevity. Lemma. Let $A B$ be one of dissecting diagonals and let $\mathcal{L}$ be the shorter part of the boundary of the 2006-gon with endpoints $A, B$. Suppose that $\mathcal{L}$ consists of $n$ segments. Then the number of iso-odd triangles with vertices on $\mathcal{L}$ does not exceed $n / 2$. Proof. This is obvious for $n=2$. Take $n$ with $2<n \leq 1003$ and assume the claim to be true for every $\mathcal{L}$ of length less than $n$. Let now $\mathcal{L}$ (endpoints $A, B$ ) consist of $n$ segments. Let $P Q$ be the longest diagonal which is a side of an iso-odd triangle $P Q S$ with all vertices on $\mathcal{L}$ (if there is no such triangle, there is nothing to prove). Every triangle whose vertices lie on $\mathcal{L}$ is obtuse or right-angled; thus $S$ is the summit of $P Q S$. We may assume that the five points $A, P, S, Q, B$ lie on $\mathcal{L}$ in this order and partition $\mathcal{L}$ into four pieces $\mathcal{L}_{A P}, \mathcal{L}_{P S}, \mathcal{L}_{S Q}, \mathcal{L}_{Q B}$ (the outer ones possibly reducing to a point). By the definition of $P Q$, an iso-odd triangle cannot have vertices on both $\mathcal{L}_{A P}$ and $\mathcal{L}_{Q B}$. Therefore every iso-odd triangle within $\mathcal{L}$ has all its vertices on just one of the four pieces. Applying to each of these pieces the induction hypothesis and adding the four inequalities we get that the number of iso-odd triangles within $\mathcal{L}$ other than $P Q S$ does not exceed $n / 2$. And since each of $\mathcal{L}_{P S}, \mathcal{L}_{S Q}$ consists of an odd number of sides, the inequalities for these two pieces are actually strict, leaving a $1 / 2+1 / 2$ in excess. Hence the triangle $P S Q$ is also covered by the estimate $n / 2$. This concludes the induction step and proves the lemma. The remaining part of the solution in fact repeats the argument from the above proof. Consider the longest dissecting diagonal $X Y$. Let $\mathcal{L}_{X Y}$ be the shorter of the two parts of the boundary with endpoints $X, Y$ and let $X Y Z$ be the triangle in the dissection with vertex $Z$ not on $\mathcal{L}_{X Y}$. Notice that $X Y Z$ is acute or right-angled, otherwise one of the segments $X Z, Y Z$ would be longer than $X Y$. Denoting by $\mathcal{L}_{X Z}, \mathcal{L}_{Y Z}$ the two pieces defined by $Z$ and applying the lemma to each of $\mathcal{L}_{X Y}, \mathcal{L}_{X Z}, \mathcal{L}_{Y Z}$ we infer that there are no more than 2006/2 iso-odd triangles in all, unless $X Y Z$ is one of them. But in that case $X Z$ and $Y Z$ are odd diagonals and the corresponding inequalities are strict. This shows that also in this case the total number of iso-odd triangles in the dissection, including $X Y Z$, is not greater than 1003 . This bound can be achieved. For this to happen, it just suffices to select a vertex of the 2006-gon and draw a broken line joining every second vertex, starting from the selected one. Since 2006 is even, the line closes. This already gives us the required 1003 iso-odd triangles. Then we can complete the triangulation in an arbitrary fashion.

|

1003

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A diagonal of a regular 2006-gon is called odd if its endpoints divide the boundary into two parts, each composed of an odd number of sides. Sides are also regarded as odd diagonals. Suppose the 2006-gon has been dissected into triangles by 2003 nonintersecting diagonals. Find the maximum possible number of isosceles triangles with two odd sides. (Serbia)

|

Call an isosceles triangle odd if it has two odd sides. Suppose we are given a dissection as in the problem statement. A triangle in the dissection which is odd and isosceles will be called iso-odd for brevity. Lemma. Let $A B$ be one of dissecting diagonals and let $\mathcal{L}$ be the shorter part of the boundary of the 2006-gon with endpoints $A, B$. Suppose that $\mathcal{L}$ consists of $n$ segments. Then the number of iso-odd triangles with vertices on $\mathcal{L}$ does not exceed $n / 2$. Proof. This is obvious for $n=2$. Take $n$ with $2<n \leq 1003$ and assume the claim to be true for every $\mathcal{L}$ of length less than $n$. Let now $\mathcal{L}$ (endpoints $A, B$ ) consist of $n$ segments. Let $P Q$ be the longest diagonal which is a side of an iso-odd triangle $P Q S$ with all vertices on $\mathcal{L}$ (if there is no such triangle, there is nothing to prove). Every triangle whose vertices lie on $\mathcal{L}$ is obtuse or right-angled; thus $S$ is the summit of $P Q S$. We may assume that the five points $A, P, S, Q, B$ lie on $\mathcal{L}$ in this order and partition $\mathcal{L}$ into four pieces $\mathcal{L}_{A P}, \mathcal{L}_{P S}, \mathcal{L}_{S Q}, \mathcal{L}_{Q B}$ (the outer ones possibly reducing to a point). By the definition of $P Q$, an iso-odd triangle cannot have vertices on both $\mathcal{L}_{A P}$ and $\mathcal{L}_{Q B}$. Therefore every iso-odd triangle within $\mathcal{L}$ has all its vertices on just one of the four pieces. Applying to each of these pieces the induction hypothesis and adding the four inequalities we get that the number of iso-odd triangles within $\mathcal{L}$ other than $P Q S$ does not exceed $n / 2$. And since each of $\mathcal{L}_{P S}, \mathcal{L}_{S Q}$ consists of an odd number of sides, the inequalities for these two pieces are actually strict, leaving a $1 / 2+1 / 2$ in excess. Hence the triangle $P S Q$ is also covered by the estimate $n / 2$. This concludes the induction step and proves the lemma. The remaining part of the solution in fact repeats the argument from the above proof. Consider the longest dissecting diagonal $X Y$. Let $\mathcal{L}_{X Y}$ be the shorter of the two parts of the boundary with endpoints $X, Y$ and let $X Y Z$ be the triangle in the dissection with vertex $Z$ not on $\mathcal{L}_{X Y}$. Notice that $X Y Z$ is acute or right-angled, otherwise one of the segments $X Z, Y Z$ would be longer than $X Y$. Denoting by $\mathcal{L}_{X Z}, \mathcal{L}_{Y Z}$ the two pieces defined by $Z$ and applying the lemma to each of $\mathcal{L}_{X Y}, \mathcal{L}_{X Z}, \mathcal{L}_{Y Z}$ we infer that there are no more than 2006/2 iso-odd triangles in all, unless $X Y Z$ is one of them. But in that case $X Z$ and $Y Z$ are odd diagonals and the corresponding inequalities are strict. This shows that also in this case the total number of iso-odd triangles in the dissection, including $X Y Z$, is not greater than 1003 . This bound can be achieved. For this to happen, it just suffices to select a vertex of the 2006-gon and draw a broken line joining every second vertex, starting from the selected one. Since 2006 is even, the line closes. This already gives us the required 1003 iso-odd triangles. Then we can complete the triangulation in an arbitrary fashion.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2006SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

5816615c-7dd4-5732-80bf-344ac953b604

| 23,548

|

Let $n>1$ be an integer. In the space, consider the set $$ S=\{(x, y, z) \mid x, y, z \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}, x+y+z>0\} $$ Find the smallest number of planes that jointly contain all $(n+1)^{3}-1$ points of $S$ but none of them passes through the origin. (Netherlands) Answer. $3 n$ planes.

|

It is easy to find $3 n$ such planes. For example, planes $x=i, y=i$ or $z=i$ $(i=1,2, \ldots, n)$ cover the set $S$ but none of them contains the origin. Another such collection consists of all planes $x+y+z=k$ for $k=1,2, \ldots, 3 n$. We show that $3 n$ is the smallest possible number. Lemma 1. Consider a nonzero polynomial $P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k}\right)$ in $k$ variables. Suppose that $P$ vanishes at all points $\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k}\right)$ such that $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k} \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ and $x_{1}+\cdots+x_{k}>0$, while $P(0,0, \ldots, 0) \neq 0$. Then $\operatorname{deg} P \geq k n$. Proof. We use induction on $k$. The base case $k=0$ is clear since $P \neq 0$. Denote for clarity $y=x_{k}$. Let $R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)$ be the residue of $P$ modulo $Q(y)=y(y-1) \ldots(y-n)$. Polynomial $Q(y)$ vanishes at each $y=0,1, \ldots, n$, hence $P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)=R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)$ for all $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$. Therefore, $R$ also satisfies the condition of the Lemma; moreover, $\operatorname{deg}_{y} R \leq n$. Clearly, $\operatorname{deg} R \leq \operatorname{deg} P$, so it suffices to prove that $\operatorname{deg} R \geq n k$. Now, expand polynomial $R$ in the powers of $y$ : $$ R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)=R_{n}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right) y^{n}+R_{n-1}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right) y^{n-1}+\cdots+R_{0}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right) $$ We show that polynomial $R_{n}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right)$ satisfies the condition of the induction hypothesis. Consider the polynomial $T(y)=R(0, \ldots, 0, y)$ of degree $\leq n$. This polynomial has $n$ roots $y=1, \ldots, n$; on the other hand, $T(y) \not \equiv 0$ since $T(0) \neq 0$. Hence $\operatorname{deg} T=n$, and its leading coefficient is $R_{n}(0,0, \ldots, 0) \neq 0$. In particular, in the case $k=1$ we obtain that coefficient $R_{n}$ is nonzero. Similarly, take any numbers $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k-1} \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ with $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k-1}>0$. Substituting $x_{i}=a_{i}$ into $R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)$, we get a polynomial in $y$ which vanishes at all points $y=0, \ldots, n$ and has degree $\leq n$. Therefore, this polynomial is null, hence $R_{i}\left(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k-1}\right)=0$ for all $i=0,1, \ldots, n$. In particular, $R_{n}\left(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k-1}\right)=0$. Thus, the polynomial $R_{n}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right)$ satisfies the condition of the induction hypothesis. So, we have $\operatorname{deg} R_{n} \geq(k-1) n$ and $\operatorname{deg} P \geq \operatorname{deg} R \geq \operatorname{deg} R_{n}+n \geq k n$. Now we can finish the solution. Suppose that there are $N$ planes covering all the points of $S$ but not containing the origin. Let their equations be $a_{i} x+b_{i} y+c_{i} z+d_{i}=0$. Consider the polynomial $$ P(x, y, z)=\prod_{i=1}^{N}\left(a_{i} x+b_{i} y+c_{i} z+d_{i}\right) $$ It has total degree $N$. This polynomial has the property that $P\left(x_{0}, y_{0}, z_{0}\right)=0$ for any $\left(x_{0}, y_{0}, z_{0}\right) \in S$, while $P(0,0,0) \neq 0$. Hence by Lemma 1 we get $N=\operatorname{deg} P \geq 3 n$, as desired. Comment 1. There are many other collections of $3 n$ planes covering the set $S$ but not covering the origin.

|

3 n

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $n>1$ be an integer. In the space, consider the set $$ S=\{(x, y, z) \mid x, y, z \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}, x+y+z>0\} $$ Find the smallest number of planes that jointly contain all $(n+1)^{3}-1$ points of $S$ but none of them passes through the origin. (Netherlands) Answer. $3 n$ planes.

|

It is easy to find $3 n$ such planes. For example, planes $x=i, y=i$ or $z=i$ $(i=1,2, \ldots, n)$ cover the set $S$ but none of them contains the origin. Another such collection consists of all planes $x+y+z=k$ for $k=1,2, \ldots, 3 n$. We show that $3 n$ is the smallest possible number. Lemma 1. Consider a nonzero polynomial $P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k}\right)$ in $k$ variables. Suppose that $P$ vanishes at all points $\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k}\right)$ such that $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k} \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ and $x_{1}+\cdots+x_{k}>0$, while $P(0,0, \ldots, 0) \neq 0$. Then $\operatorname{deg} P \geq k n$. Proof. We use induction on $k$. The base case $k=0$ is clear since $P \neq 0$. Denote for clarity $y=x_{k}$. Let $R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)$ be the residue of $P$ modulo $Q(y)=y(y-1) \ldots(y-n)$. Polynomial $Q(y)$ vanishes at each $y=0,1, \ldots, n$, hence $P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)=R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)$ for all $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$. Therefore, $R$ also satisfies the condition of the Lemma; moreover, $\operatorname{deg}_{y} R \leq n$. Clearly, $\operatorname{deg} R \leq \operatorname{deg} P$, so it suffices to prove that $\operatorname{deg} R \geq n k$. Now, expand polynomial $R$ in the powers of $y$ : $$ R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)=R_{n}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right) y^{n}+R_{n-1}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right) y^{n-1}+\cdots+R_{0}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right) $$ We show that polynomial $R_{n}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right)$ satisfies the condition of the induction hypothesis. Consider the polynomial $T(y)=R(0, \ldots, 0, y)$ of degree $\leq n$. This polynomial has $n$ roots $y=1, \ldots, n$; on the other hand, $T(y) \not \equiv 0$ since $T(0) \neq 0$. Hence $\operatorname{deg} T=n$, and its leading coefficient is $R_{n}(0,0, \ldots, 0) \neq 0$. In particular, in the case $k=1$ we obtain that coefficient $R_{n}$ is nonzero. Similarly, take any numbers $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k-1} \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ with $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k-1}>0$. Substituting $x_{i}=a_{i}$ into $R\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y\right)$, we get a polynomial in $y$ which vanishes at all points $y=0, \ldots, n$ and has degree $\leq n$. Therefore, this polynomial is null, hence $R_{i}\left(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k-1}\right)=0$ for all $i=0,1, \ldots, n$. In particular, $R_{n}\left(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k-1}\right)=0$. Thus, the polynomial $R_{n}\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{k-1}\right)$ satisfies the condition of the induction hypothesis. So, we have $\operatorname{deg} R_{n} \geq(k-1) n$ and $\operatorname{deg} P \geq \operatorname{deg} R \geq \operatorname{deg} R_{n}+n \geq k n$. Now we can finish the solution. Suppose that there are $N$ planes covering all the points of $S$ but not containing the origin. Let their equations be $a_{i} x+b_{i} y+c_{i} z+d_{i}=0$. Consider the polynomial $$ P(x, y, z)=\prod_{i=1}^{N}\left(a_{i} x+b_{i} y+c_{i} z+d_{i}\right) $$ It has total degree $N$. This polynomial has the property that $P\left(x_{0}, y_{0}, z_{0}\right)=0$ for any $\left(x_{0}, y_{0}, z_{0}\right) \in S$, while $P(0,0,0) \neq 0$. Hence by Lemma 1 we get $N=\operatorname{deg} P \geq 3 n$, as desired. Comment 1. There are many other collections of $3 n$ planes covering the set $S$ but not covering the origin.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2007SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

13039424-17f8-5aea-a6ab-71ae796ea0c1

| 23,642

|

In the coordinate plane consider the set $S$ of all points with integer coordinates. For a positive integer $k$, two distinct points $A, B \in S$ will be called $k$-friends if there is a point $C \in S$ such that the area of the triangle $A B C$ is equal to $k$. A set $T \subset S$ will be called a $k$-clique if every two points in $T$ are $k$-friends. Find the least positive integer $k$ for which there exists a $k$-clique with more than 200 elements.

|

To begin, let us describe those points $B \in S$ which are $k$-friends of the point $(0,0)$. By definition, $B=(u, v)$ satisfies this condition if and only if there is a point $C=(x, y) \in S$ such that $\frac{1}{2}|u y-v x|=k$. (This is a well-known formula expressing the area of triangle $A B C$ when $A$ is the origin.) To say that there exist integers $x, y$ for which $|u y-v x|=2 k$, is equivalent to saying that the greatest common divisor of $u$ and $v$ is also a divisor of $2 k$. Summing up, a point $B=(u, v) \in S$ is a $k$-friend of $(0,0)$ if and only if $\operatorname{gcd}(u, v)$ divides $2 k$. Translation by a vector with integer coordinates does not affect $k$-friendship; if two points are $k$-friends, so are their translates. It follows that two points $A, B \in S, A=(s, t), B=(u, v)$, are $k$-friends if and only if the point $(u-s, v-t)$ is a $k$-friend of $(0,0)$; i.e., if $\operatorname{gcd}(u-s, v-t) \mid 2 k$. Let $n$ be a positive integer which does not divide $2 k$. We claim that a $k$-clique cannot have more than $n^{2}$ elements. Indeed, all points $(x, y) \in S$ can be divided into $n^{2}$ classes determined by the remainders that $x$ and $y$ leave in division by $n$. If a set $T$ has more than $n^{2}$ elements, some two points $A, B \in T, A=(s, t), B=(u, v)$, necessarily fall into the same class. This means that $n \mid u-s$ and $n \mid v-t$. Hence $n \mid d$ where $d=\operatorname{gcd}(u-s, v-t)$. And since $n$ does not divide $2 k$, also $d$ does not divide $2 k$. Thus $A$ and $B$ are not $k$-friends and the set $T$ is not a $k$-clique. Now let $M(k)$ be the least positive integer which does not divide $2 k$. Write $M(k)=m$ for the moment and consider the set $T$ of all points $(x, y)$ with $0 \leq x, y<m$. There are $m^{2}$ of them. If $A=(s, t), B=(u, v)$ are two distinct points in $T$ then both differences $|u-s|,|v-t|$ are integers less than $m$ and at least one of them is positive. By the definition of $m$, every positive integer less than $m$ divides $2 k$. Therefore $u-s$ (if nonzero) divides $2 k$, and the same is true of $v-t$. So $2 k$ is divisible by $\operatorname{gcd}(u-s, v-t)$, meaning that $A, B$ are $k$-friends. Thus $T$ is a $k$-clique. It follows that the maximum size of a $k$-clique is $M(k)^{2}$, with $M(k)$ defined as above. We are looking for the minimum $k$ such that $M(k)^{2}>200$. By the definition of $M(k), 2 k$ is divisible by the numbers $1,2, \ldots, M(k)-1$, but not by $M(k)$ itself. If $M(k)^{2}>200$ then $M(k) \geq 15$. Trying to hit $M(k)=15$ we get a contradiction immediately ( $2 k$ would have to be divisible by 3 and 5 , but not by 15 ). So let us try $M(k)=16$. Then $2 k$ is divisible by the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 15$, hence also by their least common multiple $L$, but not by 16 . And since $L$ is not a multiple of 16 , we infer that $k=L / 2$ is the least $k$ with $M(k)=16$. Finally, observe that if $M(k) \geq 17$ then $2 k$ must be divisible by the least common multiple of $1,2, \ldots, 16$, which is equal to $2 L$. Then $2 k \geq 2 L$, yielding $k>L / 2$. In conclusion, the least $k$ with the required property is equal to $L / 2=180180$.

|

180180

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In the coordinate plane consider the set $S$ of all points with integer coordinates. For a positive integer $k$, two distinct points $A, B \in S$ will be called $k$-friends if there is a point $C \in S$ such that the area of the triangle $A B C$ is equal to $k$. A set $T \subset S$ will be called a $k$-clique if every two points in $T$ are $k$-friends. Find the least positive integer $k$ for which there exists a $k$-clique with more than 200 elements.

|

To begin, let us describe those points $B \in S$ which are $k$-friends of the point $(0,0)$. By definition, $B=(u, v)$ satisfies this condition if and only if there is a point $C=(x, y) \in S$ such that $\frac{1}{2}|u y-v x|=k$. (This is a well-known formula expressing the area of triangle $A B C$ when $A$ is the origin.) To say that there exist integers $x, y$ for which $|u y-v x|=2 k$, is equivalent to saying that the greatest common divisor of $u$ and $v$ is also a divisor of $2 k$. Summing up, a point $B=(u, v) \in S$ is a $k$-friend of $(0,0)$ if and only if $\operatorname{gcd}(u, v)$ divides $2 k$. Translation by a vector with integer coordinates does not affect $k$-friendship; if two points are $k$-friends, so are their translates. It follows that two points $A, B \in S, A=(s, t), B=(u, v)$, are $k$-friends if and only if the point $(u-s, v-t)$ is a $k$-friend of $(0,0)$; i.e., if $\operatorname{gcd}(u-s, v-t) \mid 2 k$. Let $n$ be a positive integer which does not divide $2 k$. We claim that a $k$-clique cannot have more than $n^{2}$ elements. Indeed, all points $(x, y) \in S$ can be divided into $n^{2}$ classes determined by the remainders that $x$ and $y$ leave in division by $n$. If a set $T$ has more than $n^{2}$ elements, some two points $A, B \in T, A=(s, t), B=(u, v)$, necessarily fall into the same class. This means that $n \mid u-s$ and $n \mid v-t$. Hence $n \mid d$ where $d=\operatorname{gcd}(u-s, v-t)$. And since $n$ does not divide $2 k$, also $d$ does not divide $2 k$. Thus $A$ and $B$ are not $k$-friends and the set $T$ is not a $k$-clique. Now let $M(k)$ be the least positive integer which does not divide $2 k$. Write $M(k)=m$ for the moment and consider the set $T$ of all points $(x, y)$ with $0 \leq x, y<m$. There are $m^{2}$ of them. If $A=(s, t), B=(u, v)$ are two distinct points in $T$ then both differences $|u-s|,|v-t|$ are integers less than $m$ and at least one of them is positive. By the definition of $m$, every positive integer less than $m$ divides $2 k$. Therefore $u-s$ (if nonzero) divides $2 k$, and the same is true of $v-t$. So $2 k$ is divisible by $\operatorname{gcd}(u-s, v-t)$, meaning that $A, B$ are $k$-friends. Thus $T$ is a $k$-clique. It follows that the maximum size of a $k$-clique is $M(k)^{2}$, with $M(k)$ defined as above. We are looking for the minimum $k$ such that $M(k)^{2}>200$. By the definition of $M(k), 2 k$ is divisible by the numbers $1,2, \ldots, M(k)-1$, but not by $M(k)$ itself. If $M(k)^{2}>200$ then $M(k) \geq 15$. Trying to hit $M(k)=15$ we get a contradiction immediately ( $2 k$ would have to be divisible by 3 and 5 , but not by 15 ). So let us try $M(k)=16$. Then $2 k$ is divisible by the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 15$, hence also by their least common multiple $L$, but not by 16 . And since $L$ is not a multiple of 16 , we infer that $k=L / 2$ is the least $k$ with $M(k)=16$. Finally, observe that if $M(k) \geq 17$ then $2 k$ must be divisible by the least common multiple of $1,2, \ldots, 16$, which is equal to $2 L$. Then $2 k \geq 2 L$, yielding $k>L / 2$. In conclusion, the least $k$ with the required property is equal to $L / 2=180180$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2008SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

1fc0e9b7-0711-5be2-aff5-b6aae982cf62

| 23,740

|

Let $n$ and $k$ be fixed positive integers of the same parity, $k \geq n$. We are given $2 n$ lamps numbered 1 through $2 n$; each of them can be on or off. At the beginning all lamps are off. We consider sequences of $k$ steps. At each step one of the lamps is switched (from off to on or from on to off). Let $N$ be the number of $k$-step sequences ending in the state: lamps $1, \ldots, n$ on, lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ off. Let $M$ be the number of $k$-step sequences leading to the same state and not touching lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ at all. Find the ratio $N / M$.

|

A sequence of $k$ switches ending in the state as described in the problem statement (lamps $1, \ldots, n$ on, lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ off) will be called an admissible process. If, moreover, the process does not touch the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$, it will be called restricted. So there are $N$ admissible processes, among which $M$ are restricted. In every admissible process, restricted or not, each one of the lamps $1, \ldots, n$ goes from off to on, so it is switched an odd number of times; and each one of the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ goes from off to off, so it is switched an even number of times. Notice that $M>0$; i.e., restricted admissible processes do exist (it suffices to switch each one of the lamps $1, \ldots, n$ just once and then choose one of them and switch it $k-n$ times, which by hypothesis is an even number). Consider any restricted admissible process $\mathbf{p}$. Take any lamp $\ell, 1 \leq \ell \leq n$, and suppose that it was switched $k_{\ell}$ times. As noticed, $k_{\ell}$ must be odd. Select arbitrarily an even number of these $k_{\ell}$ switches and replace each of them by the switch of lamp $n+\ell$. This can be done in $2^{k_{\ell}-1}$ ways (because a $k_{\ell}$-element set has $2^{k_{\ell}-1}$ subsets of even cardinality). Notice that $k_{1}+\cdots+k_{n}=k$. These actions are independent, in the sense that the action involving lamp $\ell$ does not affect the action involving any other lamp. So there are $2^{k_{1}-1} \cdot 2^{k_{2}-1} \cdots 2^{k_{n}-1}=2^{k-n}$ ways of combining these actions. In any of these combinations, each one of the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ gets switched an even number of times and each one of the lamps $1, \ldots, n$ remains switched an odd number of times, so the final state is the same as that resulting from the original process $\mathbf{p}$. This shows that every restricted admissible process $\mathbf{p}$ can be modified in $2^{k-n}$ ways, giving rise to $2^{k-n}$ distinct admissible processes (with all lamps allowed). Now we show that every admissible process $\mathbf{q}$ can be achieved in that way. Indeed, it is enough to replace every switch of a lamp with a label $\ell>n$ that occurs in $\mathbf{q}$ by the switch of the corresponding lamp $\ell-n$; in the resulting process $\mathbf{p}$ the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ are not involved. Switches of each lamp with a label $\ell>n$ had occurred in $\mathbf{q}$ an even number of times. So the performed replacements have affected each lamp with a label $\ell \leq n$ also an even number of times; hence in the overall effect the final state of each lamp has remained the same. This means that the resulting process $\mathbf{p}$ is admissible - and clearly restricted, as the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ are not involved in it any more. If we now take process $\mathbf{p}$ and reverse all these replacements, then we obtain process $\mathbf{q}$. These reversed replacements are nothing else than the modifications described in the foregoing paragraphs. Thus there is a one-to $-\left(2^{k-n}\right)$ correspondence between the $M$ restricted admissible processes and the total of $N$ admissible processes. Therefore $N / M=2^{k-n}$.

|

2^{k-n}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $n$ and $k$ be fixed positive integers of the same parity, $k \geq n$. We are given $2 n$ lamps numbered 1 through $2 n$; each of them can be on or off. At the beginning all lamps are off. We consider sequences of $k$ steps. At each step one of the lamps is switched (from off to on or from on to off). Let $N$ be the number of $k$-step sequences ending in the state: lamps $1, \ldots, n$ on, lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ off. Let $M$ be the number of $k$-step sequences leading to the same state and not touching lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ at all. Find the ratio $N / M$.

|

A sequence of $k$ switches ending in the state as described in the problem statement (lamps $1, \ldots, n$ on, lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ off) will be called an admissible process. If, moreover, the process does not touch the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$, it will be called restricted. So there are $N$ admissible processes, among which $M$ are restricted. In every admissible process, restricted or not, each one of the lamps $1, \ldots, n$ goes from off to on, so it is switched an odd number of times; and each one of the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ goes from off to off, so it is switched an even number of times. Notice that $M>0$; i.e., restricted admissible processes do exist (it suffices to switch each one of the lamps $1, \ldots, n$ just once and then choose one of them and switch it $k-n$ times, which by hypothesis is an even number). Consider any restricted admissible process $\mathbf{p}$. Take any lamp $\ell, 1 \leq \ell \leq n$, and suppose that it was switched $k_{\ell}$ times. As noticed, $k_{\ell}$ must be odd. Select arbitrarily an even number of these $k_{\ell}$ switches and replace each of them by the switch of lamp $n+\ell$. This can be done in $2^{k_{\ell}-1}$ ways (because a $k_{\ell}$-element set has $2^{k_{\ell}-1}$ subsets of even cardinality). Notice that $k_{1}+\cdots+k_{n}=k$. These actions are independent, in the sense that the action involving lamp $\ell$ does not affect the action involving any other lamp. So there are $2^{k_{1}-1} \cdot 2^{k_{2}-1} \cdots 2^{k_{n}-1}=2^{k-n}$ ways of combining these actions. In any of these combinations, each one of the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ gets switched an even number of times and each one of the lamps $1, \ldots, n$ remains switched an odd number of times, so the final state is the same as that resulting from the original process $\mathbf{p}$. This shows that every restricted admissible process $\mathbf{p}$ can be modified in $2^{k-n}$ ways, giving rise to $2^{k-n}$ distinct admissible processes (with all lamps allowed). Now we show that every admissible process $\mathbf{q}$ can be achieved in that way. Indeed, it is enough to replace every switch of a lamp with a label $\ell>n$ that occurs in $\mathbf{q}$ by the switch of the corresponding lamp $\ell-n$; in the resulting process $\mathbf{p}$ the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ are not involved. Switches of each lamp with a label $\ell>n$ had occurred in $\mathbf{q}$ an even number of times. So the performed replacements have affected each lamp with a label $\ell \leq n$ also an even number of times; hence in the overall effect the final state of each lamp has remained the same. This means that the resulting process $\mathbf{p}$ is admissible - and clearly restricted, as the lamps $n+1, \ldots, 2 n$ are not involved in it any more. If we now take process $\mathbf{p}$ and reverse all these replacements, then we obtain process $\mathbf{q}$. These reversed replacements are nothing else than the modifications described in the foregoing paragraphs. Thus there is a one-to $-\left(2^{k-n}\right)$ correspondence between the $M$ restricted admissible processes and the total of $N$ admissible processes. Therefore $N / M=2^{k-n}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2008SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

15a757e1-f1f1-500e-a2da-abe81a5109df

| 23,742

|

CZE Find the largest possible integer $k$, such that the following statement is true: Let 2009 arbitrary non-degenerated triangles be given. In every triangle the three sides are colored, such that one is blue, one is red and one is white. Now, for every color separately, let us sort the lengths of the sides. We obtain $$ \begin{aligned} & b_{1} \leq b_{2} \\ & \leq \ldots \leq b_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the blue sides, } \\ r_{1} & \leq r_{2} \leq \ldots \leq r_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the red sides, } \\ \text { and } \quad w_{1} & \leq w_{2} \leq \ldots \leq w_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the white sides. } \end{aligned} $$ Then there exist $k$ indices $j$ such that we can form a non-degenerated triangle with side lengths $b_{j}, r_{j}, w_{j}$ 。

|

We will prove that the largest possible number $k$ of indices satisfying the given condition is one. Firstly we prove that $b_{2009}, r_{2009}, w_{2009}$ are always lengths of the sides of a triangle. Without loss of generality we may assume that $w_{2009} \geq r_{2009} \geq b_{2009}$. We show that the inequality $b_{2009}+r_{2009}>w_{2009}$ holds. Evidently, there exists a triangle with side lengths $w, b, r$ for the white, blue and red side, respectively, such that $w_{2009}=w$. By the conditions of the problem we have $b+r>w, b_{2009} \geq b$ and $r_{2009} \geq r$. From these inequalities it follows $$ b_{2009}+r_{2009} \geq b+r>w=w_{2009} $$ Secondly we will describe a sequence of triangles for which $w_{j}, b_{j}, r_{j}$ with $j<2009$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle. Let us define the sequence $\Delta_{j}, j=1,2, \ldots, 2009$, of triangles, where $\Delta_{j}$ has a blue side of length $2 j$, a red side of length $j$ for all $j \leq 2008$ and 4018 for $j=2009$, and a white side of length $j+1$ for all $j \leq 2007$, 4018 for $j=2008$ and 1 for $j=2009$. Since $$ \begin{array}{rrrl} (j+1)+j>2 j & \geq j+1>j, & \text { if } & j \leq 2007 \\ 2 j+j>4018>2 j \quad>j, & \text { if } & j=2008 \\ 4018+1>2 j & =4018>1, & \text { if } & j=2009 \end{array} $$ such a sequence of triangles exists. Moreover, $w_{j}=j, r_{j}=j$ and $b_{j}=2 j$ for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$. Then $$ w_{j}+r_{j}=j+j=2 j=b_{j} $$ i.e., $b_{j}, r_{j}$ and $w_{j}$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$.

|

1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

CZE Find the largest possible integer $k$, such that the following statement is true: Let 2009 arbitrary non-degenerated triangles be given. In every triangle the three sides are colored, such that one is blue, one is red and one is white. Now, for every color separately, let us sort the lengths of the sides. We obtain $$ \begin{aligned} & b_{1} \leq b_{2} \\ & \leq \ldots \leq b_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the blue sides, } \\ r_{1} & \leq r_{2} \leq \ldots \leq r_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the red sides, } \\ \text { and } \quad w_{1} & \leq w_{2} \leq \ldots \leq w_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the white sides. } \end{aligned} $$ Then there exist $k$ indices $j$ such that we can form a non-degenerated triangle with side lengths $b_{j}, r_{j}, w_{j}$ 。

|

We will prove that the largest possible number $k$ of indices satisfying the given condition is one. Firstly we prove that $b_{2009}, r_{2009}, w_{2009}$ are always lengths of the sides of a triangle. Without loss of generality we may assume that $w_{2009} \geq r_{2009} \geq b_{2009}$. We show that the inequality $b_{2009}+r_{2009}>w_{2009}$ holds. Evidently, there exists a triangle with side lengths $w, b, r$ for the white, blue and red side, respectively, such that $w_{2009}=w$. By the conditions of the problem we have $b+r>w, b_{2009} \geq b$ and $r_{2009} \geq r$. From these inequalities it follows $$ b_{2009}+r_{2009} \geq b+r>w=w_{2009} $$ Secondly we will describe a sequence of triangles for which $w_{j}, b_{j}, r_{j}$ with $j<2009$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle. Let us define the sequence $\Delta_{j}, j=1,2, \ldots, 2009$, of triangles, where $\Delta_{j}$ has a blue side of length $2 j$, a red side of length $j$ for all $j \leq 2008$ and 4018 for $j=2009$, and a white side of length $j+1$ for all $j \leq 2007$, 4018 for $j=2008$ and 1 for $j=2009$. Since $$ \begin{array}{rrrl} (j+1)+j>2 j & \geq j+1>j, & \text { if } & j \leq 2007 \\ 2 j+j>4018>2 j \quad>j, & \text { if } & j=2008 \\ 4018+1>2 j & =4018>1, & \text { if } & j=2009 \end{array} $$ such a sequence of triangles exists. Moreover, $w_{j}=j, r_{j}=j$ and $b_{j}=2 j$ for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$. Then $$ w_{j}+r_{j}=j+j=2 j=b_{j} $$ i.e., $b_{j}, r_{j}$ and $w_{j}$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2009SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

67a9b319-ee7d-5944-9b7a-abb8e49053cc

| 23,794

|

CZE Find the largest possible integer $k$, such that the following statement is true: Let 2009 arbitrary non-degenerated triangles be given. In every triangle the three sides are colored, such that one is blue, one is red and one is white. Now, for every color separately, let us sort the lengths of the sides. We obtain $$ \begin{array}{rlrl} b_{1} & \leq b_{2} & \leq \ldots \leq b_{2009} \quad & \\ & & \text { the lengths of the blue sides, } \\ r_{1} & \leq r_{2} & \leq \ldots \leq r_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the red sides, } \\ w_{1} & \leq w_{2} & \leq \ldots \leq w_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the white sides. } \end{array} $$ Then there exist $k$ indices $j$ such that we can form a non-degenerated triangle with side lengths $b_{j}, r_{j}, w_{j}$ 。

|

We will prove that the largest possible number $k$ of indices satisfying the given condition is one. Firstly we prove that $b_{2009}, r_{2009}, w_{2009}$ are always lengths of the sides of a triangle. Without loss of generality we may assume that $w_{2009} \geq r_{2009} \geq b_{2009}$. We show that the inequality $b_{2009}+r_{2009}>w_{2009}$ holds. Evidently, there exists a triangle with side lengths $w, b, r$ for the white, blue and red side, respectively, such that $w_{2009}=w$. By the conditions of the problem we have $b+r>w, b_{2009} \geq b$ and $r_{2009} \geq r$. From these inequalities it follows $$ b_{2009}+r_{2009} \geq b+r>w=w_{2009} $$ Secondly we will describe a sequence of triangles for which $w_{j}, b_{j}, r_{j}$ with $j<2009$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle. Let us define the sequence $\Delta_{j}, j=1,2, \ldots, 2009$, of triangles, where $\Delta_{j}$ has a blue side of length $2 j$, a red side of length $j$ for all $j \leq 2008$ and 4018 for $j=2009$, and a white side of length $j+1$ for all $j \leq 2007$, 4018 for $j=2008$ and 1 for $j=2009$. Since $$ \begin{array}{rrrl} (j+1)+j>2 j & \geq j+1>j, & \text { if } & j \leq 2007 \\ 2 j+j>4018>2 j \quad>j, & \text { if } & j=2008 \\ 4018+1>2 j & =4018>1, & \text { if } & j=2009 \end{array} $$ such a sequence of triangles exists. Moreover, $w_{j}=j, r_{j}=j$ and $b_{j}=2 j$ for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$. Then $$ w_{j}+r_{j}=j+j=2 j=b_{j} $$ i.e., $b_{j}, r_{j}$ and $w_{j}$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$.

|

1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

CZE Find the largest possible integer $k$, such that the following statement is true: Let 2009 arbitrary non-degenerated triangles be given. In every triangle the three sides are colored, such that one is blue, one is red and one is white. Now, for every color separately, let us sort the lengths of the sides. We obtain $$ \begin{array}{rlrl} b_{1} & \leq b_{2} & \leq \ldots \leq b_{2009} \quad & \\ & & \text { the lengths of the blue sides, } \\ r_{1} & \leq r_{2} & \leq \ldots \leq r_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the red sides, } \\ w_{1} & \leq w_{2} & \leq \ldots \leq w_{2009} \quad \text { the lengths of the white sides. } \end{array} $$ Then there exist $k$ indices $j$ such that we can form a non-degenerated triangle with side lengths $b_{j}, r_{j}, w_{j}$ 。

|

We will prove that the largest possible number $k$ of indices satisfying the given condition is one. Firstly we prove that $b_{2009}, r_{2009}, w_{2009}$ are always lengths of the sides of a triangle. Without loss of generality we may assume that $w_{2009} \geq r_{2009} \geq b_{2009}$. We show that the inequality $b_{2009}+r_{2009}>w_{2009}$ holds. Evidently, there exists a triangle with side lengths $w, b, r$ for the white, blue and red side, respectively, such that $w_{2009}=w$. By the conditions of the problem we have $b+r>w, b_{2009} \geq b$ and $r_{2009} \geq r$. From these inequalities it follows $$ b_{2009}+r_{2009} \geq b+r>w=w_{2009} $$ Secondly we will describe a sequence of triangles for which $w_{j}, b_{j}, r_{j}$ with $j<2009$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle. Let us define the sequence $\Delta_{j}, j=1,2, \ldots, 2009$, of triangles, where $\Delta_{j}$ has a blue side of length $2 j$, a red side of length $j$ for all $j \leq 2008$ and 4018 for $j=2009$, and a white side of length $j+1$ for all $j \leq 2007$, 4018 for $j=2008$ and 1 for $j=2009$. Since $$ \begin{array}{rrrl} (j+1)+j>2 j & \geq j+1>j, & \text { if } & j \leq 2007 \\ 2 j+j>4018>2 j \quad>j, & \text { if } & j=2008 \\ 4018+1>2 j & =4018>1, & \text { if } & j=2009 \end{array} $$ such a sequence of triangles exists. Moreover, $w_{j}=j, r_{j}=j$ and $b_{j}=2 j$ for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$. Then $$ w_{j}+r_{j}=j+j=2 j=b_{j} $$ i.e., $b_{j}, r_{j}$ and $w_{j}$ are not the lengths of the sides of a triangle for $1 \leq j \leq 2008$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2009SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

3d17de47-6887-57fa-be6d-e92e699106e4

| 23,897

|

Let $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{100}$ be nonnegative real numbers such that $x_{i}+x_{i+1}+x_{i+2} \leq 1$ for all $i=1, \ldots, 100$ (we put $x_{101}=x_{1}, x_{102}=x_{2}$ ). Find the maximal possible value of the sum $$ S=\sum_{i=1}^{100} x_{i} x_{i+2} $$ (Russia) Answer. $\frac{25}{2}$.

|

Let $x_{2 i}=0, x_{2 i-1}=\frac{1}{2}$ for all $i=1, \ldots, 50$. Then we have $S=50 \cdot\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{25}{2}$. So, we are left to show that $S \leq \frac{25}{2}$ for all values of $x_{i}$ 's satisfying the problem conditions. Consider any $1 \leq i \leq 50$. By the problem condition, we get $x_{2 i-1} \leq 1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}$ and $x_{2 i+2} \leq 1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}$. Hence by the AM-GM inequality we get $$ \begin{aligned} x_{2 i-1} x_{2 i+1} & +x_{2 i} x_{2 i+2} \leq\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right) x_{2 i+1}+x_{2 i}\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right) \\ & =\left(x_{2 i}+x_{2 i+1}\right)\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right) \leq\left(\frac{\left(x_{2 i}+x_{2 i+1}\right)+\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right)}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{1}{4} \end{aligned} $$ Summing up these inequalities for $i=1,2, \ldots, 50$, we get the desired inequality $$ \sum_{i=1}^{50}\left(x_{2 i-1} x_{2 i+1}+x_{2 i} x_{2 i+2}\right) \leq 50 \cdot \frac{1}{4}=\frac{25}{2} $$ Comment. This solution shows that a bit more general fact holds. Namely, consider $2 n$ nonnegative numbers $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{2 n}$ in a row (with no cyclic notation) and suppose that $x_{i}+x_{i+1}+x_{i+2} \leq 1$ for all $i=1,2, \ldots, 2 n-2$. Then $\sum_{i=1}^{2 n-2} x_{i} x_{i+2} \leq \frac{n-1}{4}$. The proof is the same as above, though if might be easier to find it (for instance, applying induction). The original estimate can be obtained from this version by considering the sequence $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{100}, x_{1}, x_{2}$.

|

\frac{25}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Inequalities

|

Let $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{100}$ be nonnegative real numbers such that $x_{i}+x_{i+1}+x_{i+2} \leq 1$ for all $i=1, \ldots, 100$ (we put $x_{101}=x_{1}, x_{102}=x_{2}$ ). Find the maximal possible value of the sum $$ S=\sum_{i=1}^{100} x_{i} x_{i+2} $$ (Russia) Answer. $\frac{25}{2}$.

|

Let $x_{2 i}=0, x_{2 i-1}=\frac{1}{2}$ for all $i=1, \ldots, 50$. Then we have $S=50 \cdot\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{25}{2}$. So, we are left to show that $S \leq \frac{25}{2}$ for all values of $x_{i}$ 's satisfying the problem conditions. Consider any $1 \leq i \leq 50$. By the problem condition, we get $x_{2 i-1} \leq 1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}$ and $x_{2 i+2} \leq 1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}$. Hence by the AM-GM inequality we get $$ \begin{aligned} x_{2 i-1} x_{2 i+1} & +x_{2 i} x_{2 i+2} \leq\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right) x_{2 i+1}+x_{2 i}\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right) \\ & =\left(x_{2 i}+x_{2 i+1}\right)\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right) \leq\left(\frac{\left(x_{2 i}+x_{2 i+1}\right)+\left(1-x_{2 i}-x_{2 i+1}\right)}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{1}{4} \end{aligned} $$ Summing up these inequalities for $i=1,2, \ldots, 50$, we get the desired inequality $$ \sum_{i=1}^{50}\left(x_{2 i-1} x_{2 i+1}+x_{2 i} x_{2 i+2}\right) \leq 50 \cdot \frac{1}{4}=\frac{25}{2} $$ Comment. This solution shows that a bit more general fact holds. Namely, consider $2 n$ nonnegative numbers $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{2 n}$ in a row (with no cyclic notation) and suppose that $x_{i}+x_{i+1}+x_{i+2} \leq 1$ for all $i=1,2, \ldots, 2 n-2$. Then $\sum_{i=1}^{2 n-2} x_{i} x_{i+2} \leq \frac{n-1}{4}$. The proof is the same as above, though if might be easier to find it (for instance, applying induction). The original estimate can be obtained from this version by considering the sequence $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{100}, x_{1}, x_{2}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2010SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

a52d081b-c67d-5acf-80bd-9a0c6f9f6fdc

| 23,913

|

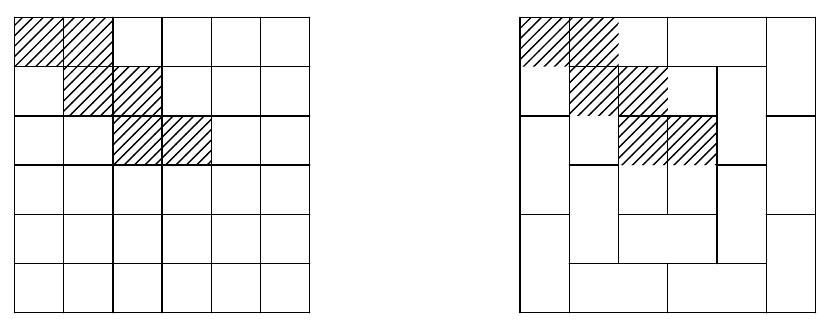

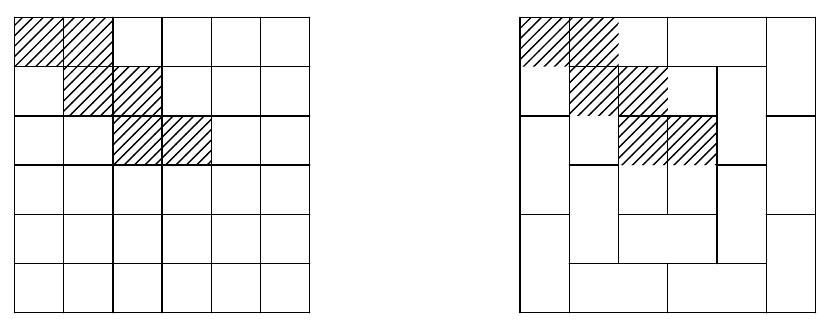

In a concert, 20 singers will perform. For each singer, there is a (possibly empty) set of other singers such that he wishes to perform later than all the singers from that set. Can it happen that there are exactly 2010 orders of the singers such that all their wishes are satisfied? (Austria) Answer. Yes, such an example exists.

|

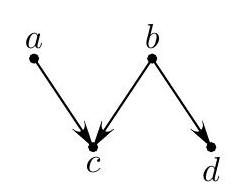

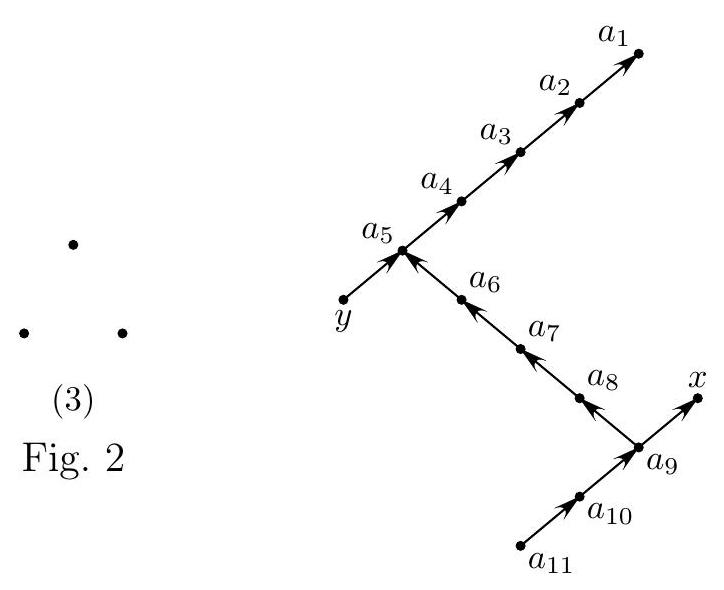

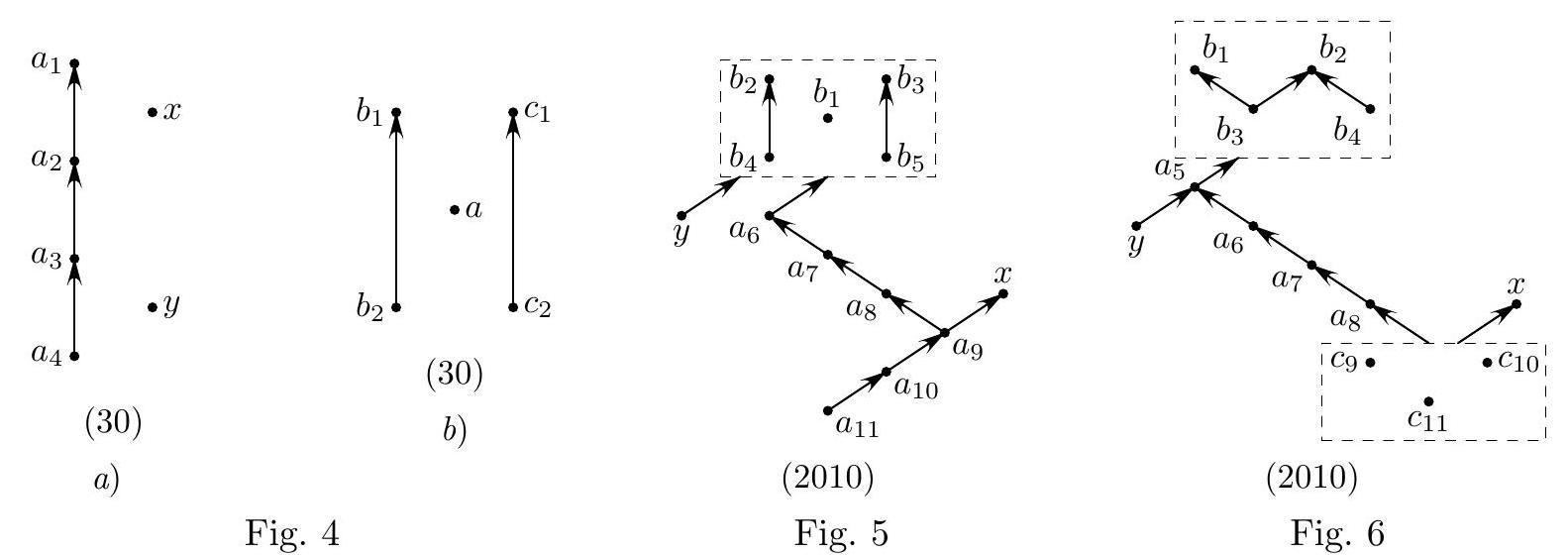

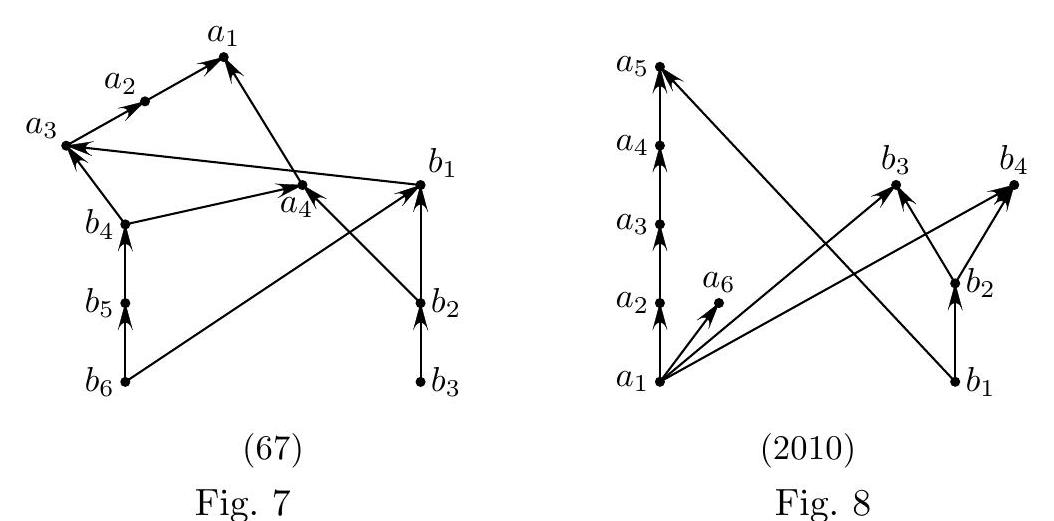

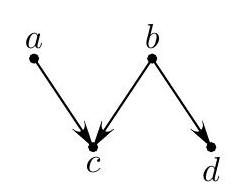

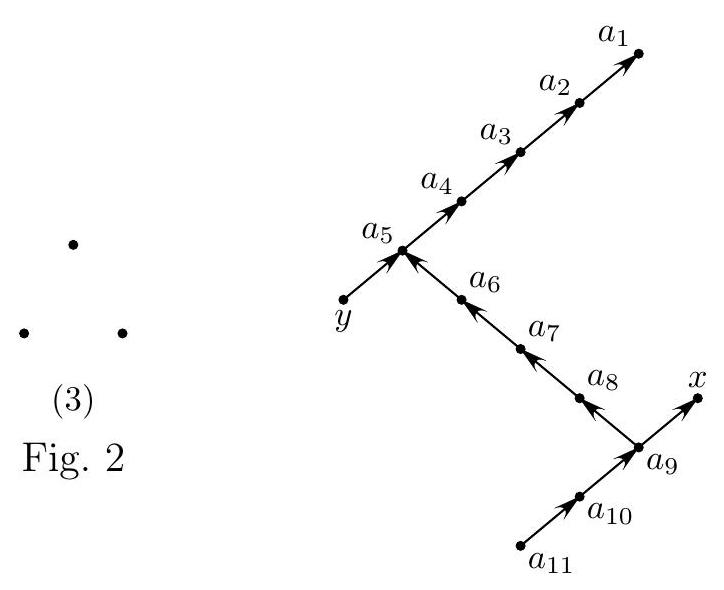

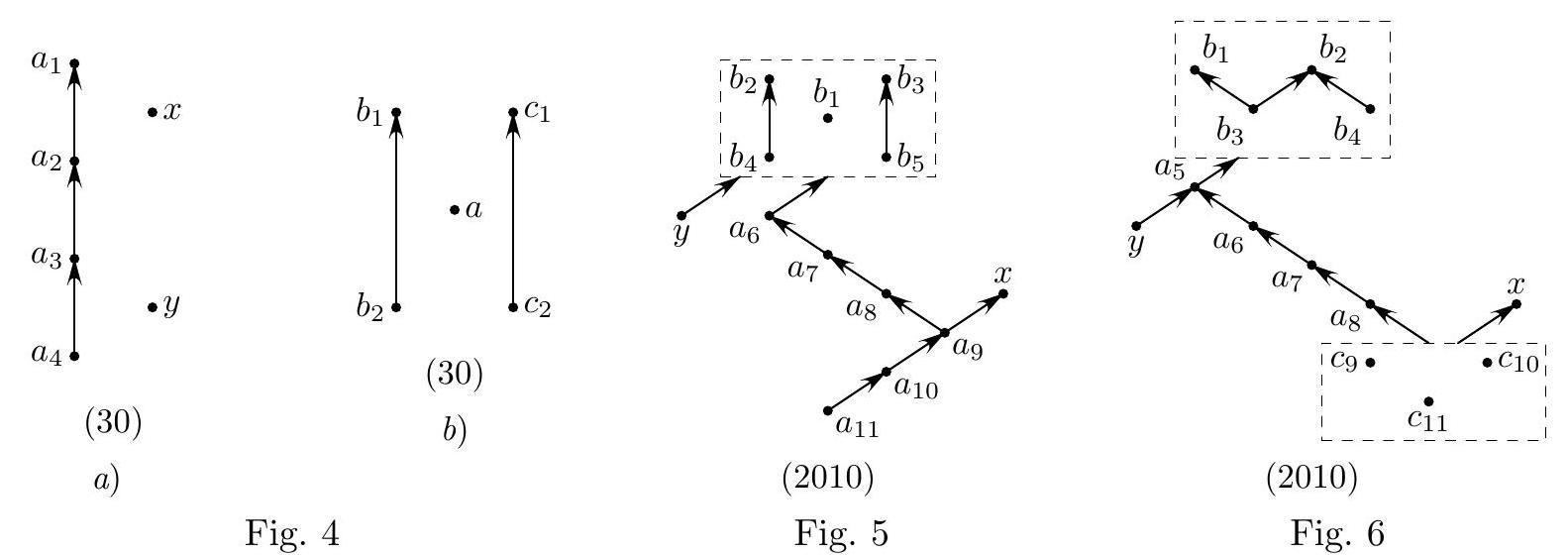

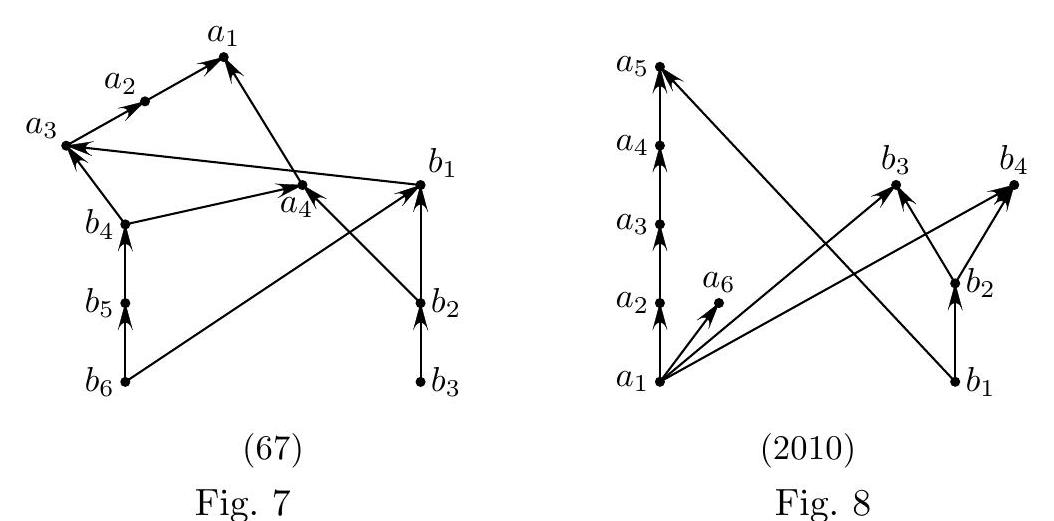

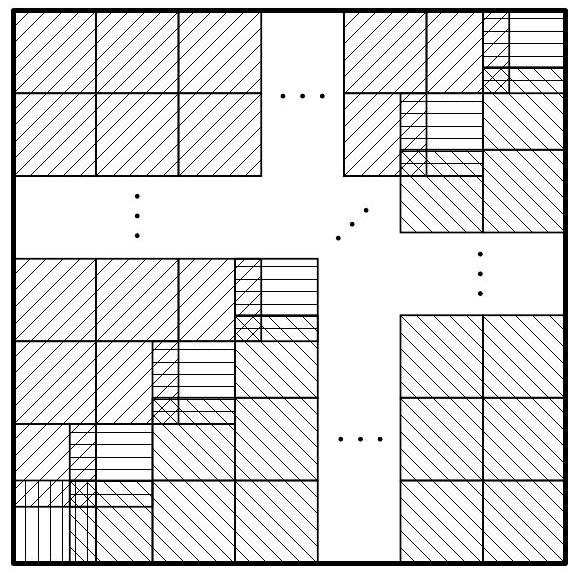

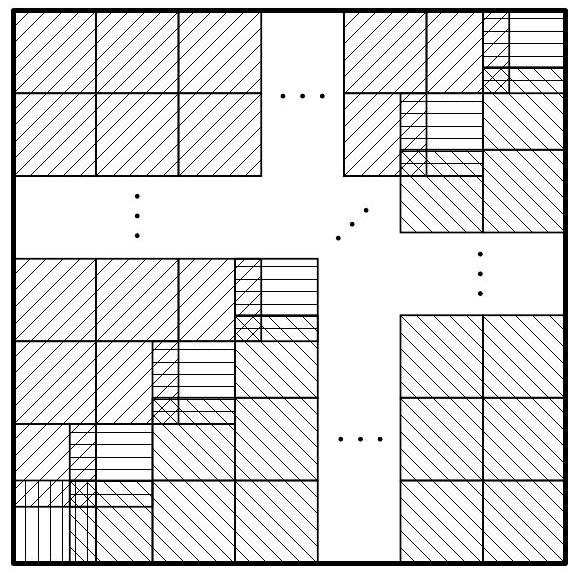

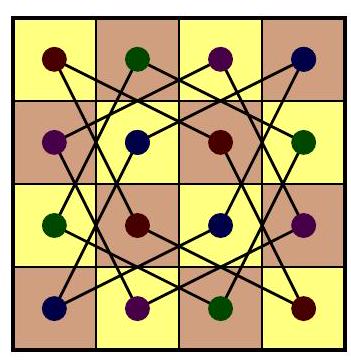

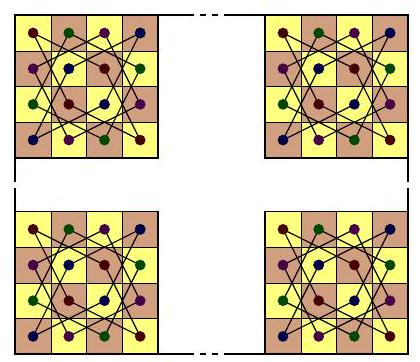

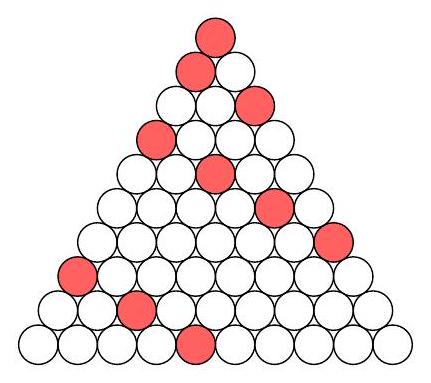

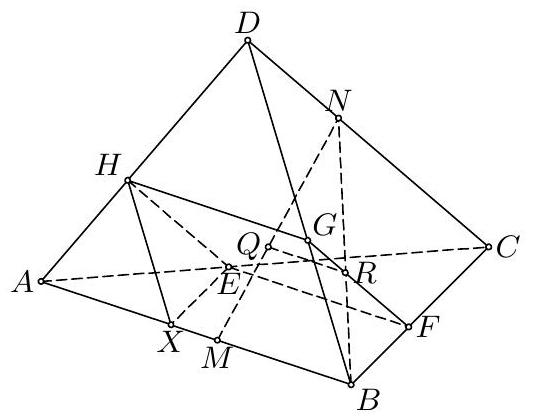

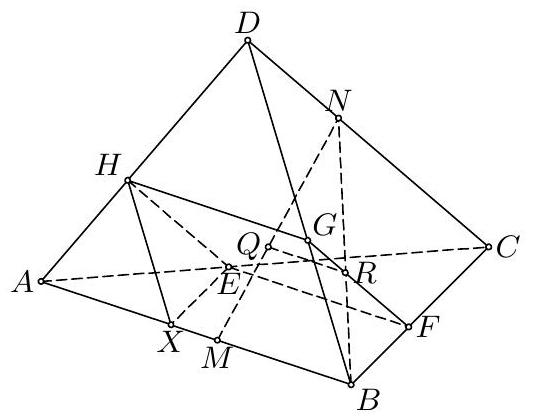

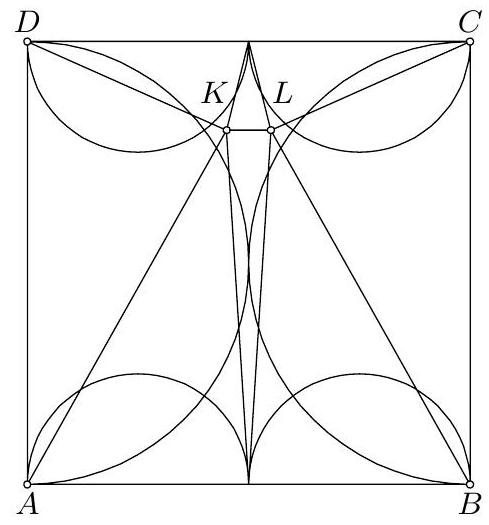

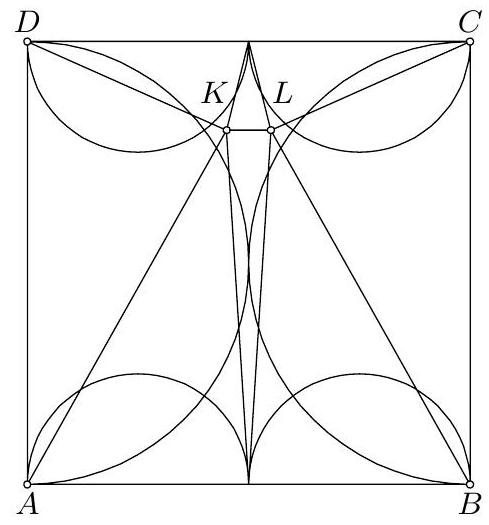

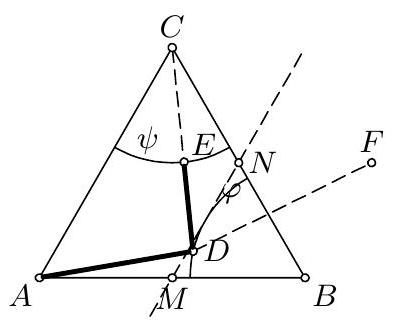

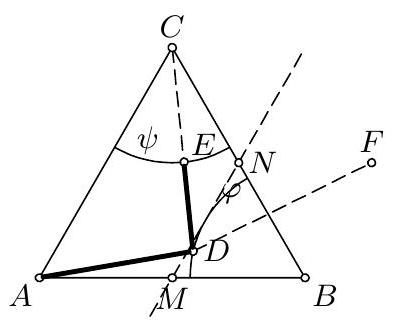

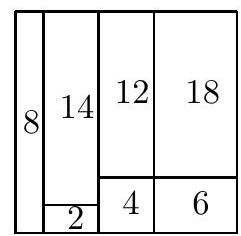

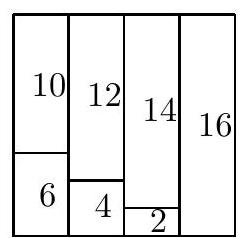

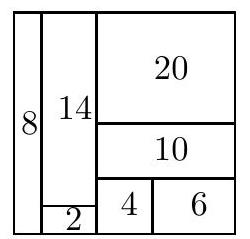

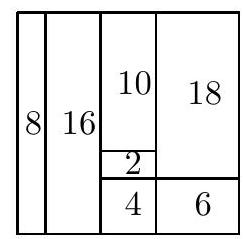

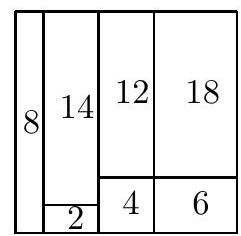

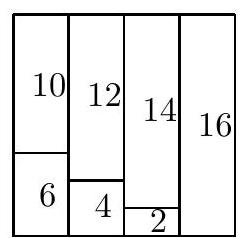

We say that an order of singers is good if it satisfied all their wishes. Next, we say that a number $N$ is realizable by $k$ singers (or $k$-realizable) if for some set of wishes of these singers there are exactly $N$ good orders. Thus, we have to prove that a number 2010 is 20-realizable. We start with the following simple Lemma. Suppose that numbers $n_{1}, n_{2}$ are realizable by respectively $k_{1}$ and $k_{2}$ singers. Then the number $n_{1} n_{2}$ is $\left(k_{1}+k_{2}\right)$-realizable. Proof. Let the singers $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{k_{1}}$ (with some wishes among them) realize $n_{1}$, and the singers $B_{1}$, $\ldots, B_{k_{2}}$ (with some wishes among them) realize $n_{2}$. Add to each singer $B_{i}$ the wish to perform later than all the singers $A_{j}$. Then, each good order of the obtained set of singers has the form $\left(A_{i_{1}}, \ldots, A_{i_{k_{1}}}, B_{j_{1}}, \ldots, B_{j_{k_{2}}}\right)$, where $\left(A_{i_{1}}, \ldots, A_{i_{k_{1}}}\right)$ is a good order for $A_{i}$ 's and $\left(B_{j_{1}}, \ldots, B_{j_{k_{2}}}\right)$ is a good order for $B_{j}$ 's. Conversely, each order of this form is obviously good. Hence, the number of good orders is $n_{1} n_{2}$. In view of Lemma, we show how to construct sets of singers containing 4, 3 and 13 singers and realizing the numbers 5, 6 and 67 , respectively. Thus the number $2010=6 \cdot 5 \cdot 67$ will be realizable by $4+3+13=20$ singers. These companies of singers are shown in Figs. 1-3; the wishes are denoted by arrows, and the number of good orders for each Figure stands below in the brackets.  (5) Fig. 1  (67) Fig. 3 For Fig. 1, there are exactly 5 good orders $(a, b, c, d),(a, b, d, c),(b, a, c, d),(b, a, d, c)$, $(b, d, a, c)$. For Fig. 2, each of 6 orders is good since there are no wishes. Finally, for Fig. 3, the order of $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{11}$ is fixed; in this line, singer $x$ can stand before each of $a_{i}(i \leq 9)$, and singer $y$ can stand after each of $a_{j}(j \geq 5)$, thus resulting in $9 \cdot 7=63$ cases. Further, the positions of $x$ and $y$ in this line determine the whole order uniquely unless both of them come between the same pair $\left(a_{i}, a_{i+1}\right)$ (thus $5 \leq i \leq 8$ ); in the latter cases, there are two orders instead of 1 due to the order of $x$ and $y$. Hence, the total number of good orders is $63+4=67$, as desired. Comment. The number 20 in the problem statement is not sharp and is put there to respect the original formulation. So, if necessary, the difficulty level of this problem may be adjusted by replacing 20 by a smaller number. Here we present some improvements of the example leading to a smaller number of singers. Surely, each example with $<20$ singers can be filled with some "super-stars" who should perform at the very end in a fixed order. Hence each of these improvements provides a different solution for the problem. Moreover, the large variety of ideas standing behind these examples allows to suggest that there are many other examples. 1. Instead of building the examples realizing 5 and 6 , it is more economic to make an example realizing 30; it may seem even simpler. Two possible examples consisting of 5 and 6 singers are shown in Fig. 4; hence the number 20 can be decreased to 19 or 18 . For Fig. 4a, the order of $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{4}$ is fixed, there are 5 ways to add $x$ into this order, and there are 6 ways to add $y$ into the resulting order of $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{4}, x$. Hence there are $5 \cdot 6=30$ good orders. On Fig. 4b, for 5 singers $a, b_{1}, b_{2}, c_{1}, c_{2}$ there are $5!=120$ orders at all. Obviously, exactly one half of them satisfies the wish $b_{1} \leftarrow b_{2}$, and exactly one half of these orders satisfies another wish $c_{1} \leftarrow c_{2}$; hence, there are exactly $5!/ 4=30$ good orders.  2. One can merge the examples for 30 and 67 shown in Figs. 4 b and 3 in a smarter way, obtaining a set of 13 singers representing 2010. This example is shown in Fig. 5; an arrow from/to group $\left\{b_{1}, \ldots, b_{5}\right\}$ means that there exists such arrow from each member of this group. Here, as in Fig. 4b, one can see that there are exactly 30 orders of $b_{1}, \ldots, b_{5}, a_{6}, \ldots, a_{11}$ satisfying all their wishes among themselves. Moreover, one can prove in the same way as for Fig. 3 that each of these orders can be complemented by $x$ and $y$ in exactly 67 ways, hence obtaining $30 \cdot 67=2010$ good orders at all. Analogously, one can merge the examples in Figs. 1-3 to represent 2010 by 13 singers as is shown in Fig. 6.  3. Finally, we will present two other improvements; the proofs are left to the reader. The graph in Fig. 7 shows how 10 singers can represent 67 . Moreover, even a company of 10 singers representing 2010 can be found; this company is shown in Fig. 8.

|

2010

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In a concert, 20 singers will perform. For each singer, there is a (possibly empty) set of other singers such that he wishes to perform later than all the singers from that set. Can it happen that there are exactly 2010 orders of the singers such that all their wishes are satisfied? (Austria) Answer. Yes, such an example exists.

|

We say that an order of singers is good if it satisfied all their wishes. Next, we say that a number $N$ is realizable by $k$ singers (or $k$-realizable) if for some set of wishes of these singers there are exactly $N$ good orders. Thus, we have to prove that a number 2010 is 20-realizable. We start with the following simple Lemma. Suppose that numbers $n_{1}, n_{2}$ are realizable by respectively $k_{1}$ and $k_{2}$ singers. Then the number $n_{1} n_{2}$ is $\left(k_{1}+k_{2}\right)$-realizable. Proof. Let the singers $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{k_{1}}$ (with some wishes among them) realize $n_{1}$, and the singers $B_{1}$, $\ldots, B_{k_{2}}$ (with some wishes among them) realize $n_{2}$. Add to each singer $B_{i}$ the wish to perform later than all the singers $A_{j}$. Then, each good order of the obtained set of singers has the form $\left(A_{i_{1}}, \ldots, A_{i_{k_{1}}}, B_{j_{1}}, \ldots, B_{j_{k_{2}}}\right)$, where $\left(A_{i_{1}}, \ldots, A_{i_{k_{1}}}\right)$ is a good order for $A_{i}$ 's and $\left(B_{j_{1}}, \ldots, B_{j_{k_{2}}}\right)$ is a good order for $B_{j}$ 's. Conversely, each order of this form is obviously good. Hence, the number of good orders is $n_{1} n_{2}$. In view of Lemma, we show how to construct sets of singers containing 4, 3 and 13 singers and realizing the numbers 5, 6 and 67 , respectively. Thus the number $2010=6 \cdot 5 \cdot 67$ will be realizable by $4+3+13=20$ singers. These companies of singers are shown in Figs. 1-3; the wishes are denoted by arrows, and the number of good orders for each Figure stands below in the brackets.  (5) Fig. 1  (67) Fig. 3 For Fig. 1, there are exactly 5 good orders $(a, b, c, d),(a, b, d, c),(b, a, c, d),(b, a, d, c)$, $(b, d, a, c)$. For Fig. 2, each of 6 orders is good since there are no wishes. Finally, for Fig. 3, the order of $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{11}$ is fixed; in this line, singer $x$ can stand before each of $a_{i}(i \leq 9)$, and singer $y$ can stand after each of $a_{j}(j \geq 5)$, thus resulting in $9 \cdot 7=63$ cases. Further, the positions of $x$ and $y$ in this line determine the whole order uniquely unless both of them come between the same pair $\left(a_{i}, a_{i+1}\right)$ (thus $5 \leq i \leq 8$ ); in the latter cases, there are two orders instead of 1 due to the order of $x$ and $y$. Hence, the total number of good orders is $63+4=67$, as desired. Comment. The number 20 in the problem statement is not sharp and is put there to respect the original formulation. So, if necessary, the difficulty level of this problem may be adjusted by replacing 20 by a smaller number. Here we present some improvements of the example leading to a smaller number of singers. Surely, each example with $<20$ singers can be filled with some "super-stars" who should perform at the very end in a fixed order. Hence each of these improvements provides a different solution for the problem. Moreover, the large variety of ideas standing behind these examples allows to suggest that there are many other examples. 1. Instead of building the examples realizing 5 and 6 , it is more economic to make an example realizing 30; it may seem even simpler. Two possible examples consisting of 5 and 6 singers are shown in Fig. 4; hence the number 20 can be decreased to 19 or 18 . For Fig. 4a, the order of $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{4}$ is fixed, there are 5 ways to add $x$ into this order, and there are 6 ways to add $y$ into the resulting order of $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{4}, x$. Hence there are $5 \cdot 6=30$ good orders. On Fig. 4b, for 5 singers $a, b_{1}, b_{2}, c_{1}, c_{2}$ there are $5!=120$ orders at all. Obviously, exactly one half of them satisfies the wish $b_{1} \leftarrow b_{2}$, and exactly one half of these orders satisfies another wish $c_{1} \leftarrow c_{2}$; hence, there are exactly $5!/ 4=30$ good orders.  2. One can merge the examples for 30 and 67 shown in Figs. 4 b and 3 in a smarter way, obtaining a set of 13 singers representing 2010. This example is shown in Fig. 5; an arrow from/to group $\left\{b_{1}, \ldots, b_{5}\right\}$ means that there exists such arrow from each member of this group. Here, as in Fig. 4b, one can see that there are exactly 30 orders of $b_{1}, \ldots, b_{5}, a_{6}, \ldots, a_{11}$ satisfying all their wishes among themselves. Moreover, one can prove in the same way as for Fig. 3 that each of these orders can be complemented by $x$ and $y$ in exactly 67 ways, hence obtaining $30 \cdot 67=2010$ good orders at all. Analogously, one can merge the examples in Figs. 1-3 to represent 2010 by 13 singers as is shown in Fig. 6.  3. Finally, we will present two other improvements; the proofs are left to the reader. The graph in Fig. 7 shows how 10 singers can represent 67 . Moreover, even a company of 10 singers representing 2010 can be found; this company is shown in Fig. 8.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2010SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

8448cec8-e96e-564c-b232-7b7d3b121cfa

| 23,936

|

On some planet, there are $2^{N}$ countries $(N \geq 4)$. Each country has a flag $N$ units wide and one unit high composed of $N$ fields of size $1 \times 1$, each field being either yellow or blue. No two countries have the same flag. We say that a set of $N$ flags is diverse if these flags can be arranged into an $N \times N$ square so that all $N$ fields on its main diagonal will have the same color. Determine the smallest positive integer $M$ such that among any $M$ distinct flags, there exist $N$ flags forming a diverse set. (Croatia) Answer. $M=2^{N-2}+1$.

|

When speaking about the diagonal of a square, we will always mean the main diagonal. Let $M_{N}$ be the smallest positive integer satisfying the problem condition. First, we show that $M_{N}>2^{N-2}$. Consider the collection of all $2^{N-2}$ flags having yellow first squares and blue second ones. Obviously, both colors appear on the diagonal of each $N \times N$ square formed by these flags. We are left to show that $M_{N} \leq 2^{N-2}+1$, thus obtaining the desired answer. We start with establishing this statement for $N=4$. Suppose that we have 5 flags of length 4 . We decompose each flag into two parts of 2 squares each; thereby, we denote each flag as $L R$, where the $2 \times 1$ flags $L, R \in \mathcal{S}=\{\mathrm{BB}, \mathrm{BY}, \mathrm{YB}, \mathrm{YY}\}$ are its left and right parts, respectively. First, we make two easy observations on the flags $2 \times 1$ which can be checked manually. (i) For each $A \in \mathcal{S}$, there exists only one $2 \times 1$ flag $C \in \mathcal{S}$ (possibly $C=A$ ) such that $A$ and $C$ cannot form a $2 \times 2$ square with monochrome diagonal (for part BB, that is YY, and for BY that is YB). (ii) Let $A_{1}, A_{2}, A_{3} \in \mathcal{S}$ be three distinct elements; then two of them can form a $2 \times 2$ square with yellow diagonal, and two of them can form a $2 \times 2$ square with blue diagonal (for all parts but BB , a pair $(\mathrm{BY}, \mathrm{YB})$ fits for both statements, while for all parts but BY, these pairs are $(\mathrm{YB}, \mathrm{YY})$ and (BB, YB)). Now, let $\ell$ and $r$ be the numbers of distinct left and right parts of our 5 flags, respectively. The total number of flags is $5 \leq r \ell$, hence one of the factors (say, $r$ ) should be at least 3 . On the other hand, $\ell, r \leq 4$, so there are two flags with coinciding right part; let them be $L_{1} R_{1}$ and $L_{2} R_{1}\left(L_{1} \neq L_{2}\right)$. Next, since $r \geq 3$, there exist some flags $L_{3} R_{3}$ and $L_{4} R_{4}$ such that $R_{1}, R_{3}, R_{4}$ are distinct. Let $L^{\prime} R^{\prime}$ be the remaining flag. By (i), one of the pairs $\left(L^{\prime}, L_{1}\right)$ and $\left(L^{\prime}, L_{2}\right)$ can form a $2 \times 2$ square with monochrome diagonal; we can assume that $L^{\prime}, L_{2}$ form a square with a blue diagonal. Finally, the right parts of two of the flags $L_{1} R_{1}, L_{3} R_{3}, L_{4} R_{4}$ can also form a $2 \times 2$ square with a blue diagonal by (ii). Putting these $2 \times 2$ squares on the diagonal of a $4 \times 4$ square, we find a desired arrangement of four flags. We are ready to prove the problem statement by induction on $N$; actually, above we have proved the base case $N=4$. For the induction step, assume that $N>4$, consider any $2^{N-2}+1$ flags of length $N$, and arrange them into a large flag of size $\left(2^{N-2}+1\right) \times N$. This flag contains a non-monochrome column since the flags are distinct; we may assume that this column is the first one. By the pigeonhole principle, this column contains at least $\left\lceil\frac{2^{N-2}+1}{2}\right\rceil=2^{N-3}+1$ squares of one color (say, blue). We call the flags with a blue first square good. Consider all the good flags and remove the first square from each of them. We obtain at least $2^{N-3}+1 \geq M_{N-1}$ flags of length $N-1$; by the induction hypothesis, $N-1$ of them can form a square $Q$ with the monochrome diagonal. Now, returning the removed squares, we obtain a rectangle $(N-1) \times N$, and our aim is to supplement it on the top by one more flag. If $Q$ has a yellow diagonal, then we can take each flag with a yellow first square (it exists by a choice of the first column; moreover, it is not used in $Q$ ). Conversely, if the diagonal of $Q$ is blue then we can take any of the $\geq 2^{N-3}+1-(N-1)>0$ remaining good flags. So, in both cases we get a desired $N \times N$ square.

|

2^{N-2}+1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

On some planet, there are $2^{N}$ countries $(N \geq 4)$. Each country has a flag $N$ units wide and one unit high composed of $N$ fields of size $1 \times 1$, each field being either yellow or blue. No two countries have the same flag. We say that a set of $N$ flags is diverse if these flags can be arranged into an $N \times N$ square so that all $N$ fields on its main diagonal will have the same color. Determine the smallest positive integer $M$ such that among any $M$ distinct flags, there exist $N$ flags forming a diverse set. (Croatia) Answer. $M=2^{N-2}+1$.

|

When speaking about the diagonal of a square, we will always mean the main diagonal. Let $M_{N}$ be the smallest positive integer satisfying the problem condition. First, we show that $M_{N}>2^{N-2}$. Consider the collection of all $2^{N-2}$ flags having yellow first squares and blue second ones. Obviously, both colors appear on the diagonal of each $N \times N$ square formed by these flags. We are left to show that $M_{N} \leq 2^{N-2}+1$, thus obtaining the desired answer. We start with establishing this statement for $N=4$. Suppose that we have 5 flags of length 4 . We decompose each flag into two parts of 2 squares each; thereby, we denote each flag as $L R$, where the $2 \times 1$ flags $L, R \in \mathcal{S}=\{\mathrm{BB}, \mathrm{BY}, \mathrm{YB}, \mathrm{YY}\}$ are its left and right parts, respectively. First, we make two easy observations on the flags $2 \times 1$ which can be checked manually. (i) For each $A \in \mathcal{S}$, there exists only one $2 \times 1$ flag $C \in \mathcal{S}$ (possibly $C=A$ ) such that $A$ and $C$ cannot form a $2 \times 2$ square with monochrome diagonal (for part BB, that is YY, and for BY that is YB). (ii) Let $A_{1}, A_{2}, A_{3} \in \mathcal{S}$ be three distinct elements; then two of them can form a $2 \times 2$ square with yellow diagonal, and two of them can form a $2 \times 2$ square with blue diagonal (for all parts but BB , a pair $(\mathrm{BY}, \mathrm{YB})$ fits for both statements, while for all parts but BY, these pairs are $(\mathrm{YB}, \mathrm{YY})$ and (BB, YB)). Now, let $\ell$ and $r$ be the numbers of distinct left and right parts of our 5 flags, respectively. The total number of flags is $5 \leq r \ell$, hence one of the factors (say, $r$ ) should be at least 3 . On the other hand, $\ell, r \leq 4$, so there are two flags with coinciding right part; let them be $L_{1} R_{1}$ and $L_{2} R_{1}\left(L_{1} \neq L_{2}\right)$. Next, since $r \geq 3$, there exist some flags $L_{3} R_{3}$ and $L_{4} R_{4}$ such that $R_{1}, R_{3}, R_{4}$ are distinct. Let $L^{\prime} R^{\prime}$ be the remaining flag. By (i), one of the pairs $\left(L^{\prime}, L_{1}\right)$ and $\left(L^{\prime}, L_{2}\right)$ can form a $2 \times 2$ square with monochrome diagonal; we can assume that $L^{\prime}, L_{2}$ form a square with a blue diagonal. Finally, the right parts of two of the flags $L_{1} R_{1}, L_{3} R_{3}, L_{4} R_{4}$ can also form a $2 \times 2$ square with a blue diagonal by (ii). Putting these $2 \times 2$ squares on the diagonal of a $4 \times 4$ square, we find a desired arrangement of four flags. We are ready to prove the problem statement by induction on $N$; actually, above we have proved the base case $N=4$. For the induction step, assume that $N>4$, consider any $2^{N-2}+1$ flags of length $N$, and arrange them into a large flag of size $\left(2^{N-2}+1\right) \times N$. This flag contains a non-monochrome column since the flags are distinct; we may assume that this column is the first one. By the pigeonhole principle, this column contains at least $\left\lceil\frac{2^{N-2}+1}{2}\right\rceil=2^{N-3}+1$ squares of one color (say, blue). We call the flags with a blue first square good. Consider all the good flags and remove the first square from each of them. We obtain at least $2^{N-3}+1 \geq M_{N-1}$ flags of length $N-1$; by the induction hypothesis, $N-1$ of them can form a square $Q$ with the monochrome diagonal. Now, returning the removed squares, we obtain a rectangle $(N-1) \times N$, and our aim is to supplement it on the top by one more flag. If $Q$ has a yellow diagonal, then we can take each flag with a yellow first square (it exists by a choice of the first column; moreover, it is not used in $Q$ ). Conversely, if the diagonal of $Q$ is blue then we can take any of the $\geq 2^{N-3}+1-(N-1)>0$ remaining good flags. So, in both cases we get a desired $N \times N$ square.

|

{

"resource_path": "IMO/segmented/en-IMO2010SL.jsonl",

"problem_match": null,

"solution_match": null

}

|

9520af31-fa45-50de-b7a3-43a6338f847e

| 23,939

|