problem

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution

stringlengths 3

10k

| answer

stringlengths 1

91

| problem_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | question_type

stringclasses 1

value | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 3

10k

| metadata

dict | uuid

stringlengths 36

36

| id

int64 22.6k

612k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

All the squares of a $2024 \times 2024$ board are coloured white. In one move, Mohit can select one row or column whose every square is white, choose exactly 1000 squares in this row or column, and colour all of them red. Find the maximum number of squares that Mohit can colour red in a finite number of moves.

|

Let $n=2024$ and $k=1000$. We claim that the maximum number of squares that can be coloured in this way is $k(2 n-k)$, which evaluates to 3048000 .

Indeed, call a row/column bad if it has at least one red square. After the first move, there are exactly $k+1$ bad rows and columns: if a row was picked, then that row and the $k$ columns corresponding to the chosen squares are all bad. Any subsequent move increases the number of bad rows/columns by at least 1 . Since there are only $2 n$ rows and columns, we can make at most $2 n-(k+1)$ moves after the first one, and so at most $2 n-k$ moves can be made in total. Thus we can have at most $k(2 n-k)$ red squares.

To prove this is achievable, let's choose each of the $n$ columns in the first $n$ moves, and colour the top $k$ cells in these columns. Then, the bottom $n-k$ rows are still uncoloured, so we can make $n-k$ more moves, colouring $k(n+n-k)$ cells in total.

|

3048000

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

All the squares of a $2024 \times 2024$ board are coloured white. In one move, Mohit can select one row or column whose every square is white, choose exactly 1000 squares in this row or column, and colour all of them red. Find the maximum number of squares that Mohit can colour red in a finite number of moves.

|

Let $n=2024$ and $k=1000$. We claim that the maximum number of squares that can be coloured in this way is $k(2 n-k)$, which evaluates to 3048000 .

Indeed, call a row/column bad if it has at least one red square. After the first move, there are exactly $k+1$ bad rows and columns: if a row was picked, then that row and the $k$ columns corresponding to the chosen squares are all bad. Any subsequent move increases the number of bad rows/columns by at least 1 . Since there are only $2 n$ rows and columns, we can make at most $2 n-(k+1)$ moves after the first one, and so at most $2 n-k$ moves can be made in total. Thus we can have at most $k(2 n-k)$ red squares.

To prove this is achievable, let's choose each of the $n$ columns in the first $n$ moves, and colour the top $k$ cells in these columns. Then, the bottom $n-k$ rows are still uncoloured, so we can make $n-k$ more moves, colouring $k(n+n-k)$ cells in total.

|

{

"resource_path": "INMO/segmented/en-INMO_2024_final_solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

|

76b55b7c-d06c-5556-9e24-7c48fbffd38a

| 607,873

|

There are four basket-ball players $A, B, C, D$. Initially, the ball is with $A$. The ball is always passed from one person to a different person. In how many ways can the ball come back to $A$ after seven passes? (For example $A \rightarrow C \rightarrow B \rightarrow D \rightarrow A \rightarrow B \rightarrow C \rightarrow A$ and

$A \rightarrow D \rightarrow A \rightarrow D \rightarrow C \rightarrow A \rightarrow B \rightarrow A$ are two ways in which the ball can come back to $A$ after seven passes.)

|

Let $x_{n}$ be the number of ways in which $A$ can get back the ball after $n$ passes. Let $y_{n}$ be the number of ways in which the ball goes back to a fixed person other than $A$ after $n$ passes. Then

$$

x_{n}=3 y_{n-1} \text {, }

$$

and

$$

y_{n}=x_{n-1}+2 y_{n-1}

$$

We also have $x_{1}=0, x_{2}=3, y_{1}=1$ and $y_{2}=2$.

Eliminating $y_{n}$ and $y_{n-1}$, we get $x_{n+1}=3 x_{n-1}+2 x_{n}$. Thus

$$

\begin{aligned}

& x_{3}=3 x_{1}+2 x_{2}=2 \times 3=6 \\

& x_{4}=3 x_{2}+2 x_{3}=(3 \times 3)+(2 \times 6)=9+12=21 \\

& x_{5}=3 x_{3}+2 x_{4}=(3 \times 6)+(2 \times 21)=18+42=60 \\

& x_{6}=3 x_{4}+2 x_{5}=(3 \times 21)+(2 \times 60)=63+120=183 \\

& x_{7}=3 x_{5}+2 x_{6}=(3 \times 60)+(2 \times 183)=180+366=546

\end{aligned}

$$

Alternate solution: Since the ball goes back to one of the other 3 persons, we have

$$

x_{n}+3 y_{n}=3^{n}

$$

since there are $3^{n}$ ways of passing the ball in $n$ passes. Using $x_{n}=$ $3 y_{n-1}$, we obtain

$$

x_{n-1}+x_{n}=3^{n-1}

$$

with $x_{1}=0$. Thus

$$

\begin{array}{r}

x_{7}=3^{6}-x_{6}=3^{6}-3^{5}+x_{5}=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-x_{4}=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-3^{3}+x_{3} \\

=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-3^{3}+3^{2}-x_{2}=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-3^{3}+3^{2}-3 \\

=\left(2 \times 3^{5}\right)+\left(2 \times 3^{3}\right)+(2 \times 3)=486+54+6=546

\end{array}

$$

|

546

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

There are four basket-ball players $A, B, C, D$. Initially, the ball is with $A$. The ball is always passed from one person to a different person. In how many ways can the ball come back to $A$ after seven passes? (For example $A \rightarrow C \rightarrow B \rightarrow D \rightarrow A \rightarrow B \rightarrow C \rightarrow A$ and

$A \rightarrow D \rightarrow A \rightarrow D \rightarrow C \rightarrow A \rightarrow B \rightarrow A$ are two ways in which the ball can come back to $A$ after seven passes.)

|

Let $x_{n}$ be the number of ways in which $A$ can get back the ball after $n$ passes. Let $y_{n}$ be the number of ways in which the ball goes back to a fixed person other than $A$ after $n$ passes. Then

$$

x_{n}=3 y_{n-1} \text {, }

$$

and

$$

y_{n}=x_{n-1}+2 y_{n-1}

$$

We also have $x_{1}=0, x_{2}=3, y_{1}=1$ and $y_{2}=2$.

Eliminating $y_{n}$ and $y_{n-1}$, we get $x_{n+1}=3 x_{n-1}+2 x_{n}$. Thus

$$

\begin{aligned}

& x_{3}=3 x_{1}+2 x_{2}=2 \times 3=6 \\

& x_{4}=3 x_{2}+2 x_{3}=(3 \times 3)+(2 \times 6)=9+12=21 \\

& x_{5}=3 x_{3}+2 x_{4}=(3 \times 6)+(2 \times 21)=18+42=60 \\

& x_{6}=3 x_{4}+2 x_{5}=(3 \times 21)+(2 \times 60)=63+120=183 \\

& x_{7}=3 x_{5}+2 x_{6}=(3 \times 60)+(2 \times 183)=180+366=546

\end{aligned}

$$

Alternate solution: Since the ball goes back to one of the other 3 persons, we have

$$

x_{n}+3 y_{n}=3^{n}

$$

since there are $3^{n}$ ways of passing the ball in $n$ passes. Using $x_{n}=$ $3 y_{n-1}$, we obtain

$$

x_{n-1}+x_{n}=3^{n-1}

$$

with $x_{1}=0$. Thus

$$

\begin{array}{r}

x_{7}=3^{6}-x_{6}=3^{6}-3^{5}+x_{5}=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-x_{4}=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-3^{3}+x_{3} \\

=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-3^{3}+3^{2}-x_{2}=3^{6}-3^{5}+3^{4}-3^{3}+3^{2}-3 \\

=\left(2 \times 3^{5}\right)+\left(2 \times 3^{3}\right)+(2 \times 3)=486+54+6=546

\end{array}

$$

|

{

"resource_path": "INMO/segmented/en-inmosol-15.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:"

}

|

e5360540-52f5-5320-bad2-e8c0ac460da2

| 607,899

|

Let $X=\{0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}$. Let $S \subseteq X$ be such that any nonnegative integer $n$ can be written as $p+q$ where the nonnegative integers $p, q$ have all their digits in $S$. Find the smallest possible number of elements in $S$.

|

We show that 5 numbers will suffice. Take $S=\{0,1,3,4,6\}$. Observe the following splitting:

| $n$ | $a$ | $b$ |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | 1 | 4 |

| 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | 4 | 4 |

| 9 | 3 | 6 |

Thus each digit in a given nonnegative integer is split according to the above and can be written as a sum of two numbers each having digits in $S$.

We show that $|S|>4$. Suppose $|S| \leq 4$. We may take $|S|=4$ as adding extra numbers to $S$ does not alter our argument. Let $S=\{a, b, c, d\}$. Since the last digit can be any one of the numbers $0,1,2, \ldots, 9$, we must be able to write this as a sum of digits from $S$, modulo 10. Thus the collection

$$

A=\{x+y \quad(\bmod 10) \mid x, y \in S\}

$$

must contain $\{0,1,2, \ldots, 9\}$ as a subset. But $A$ has at most 10 elements $\left(\binom{4}{2}+4\right)$. Thus each element of the form $x+y(\bmod 10)$, as $x, y$ vary over $S$, must give different numbers from $\{0,1,2, \ldots, 9\}$.

Consider $a+a, b+b, c+c, d+d$ modulo 10. They must give 4 even numbers. Hence the remaining even number must be from the remaining 6 elements obtained by adding two distinct members of $S$. We may assume that even number is $a+b(\bmod 10)$. Then $a, b$ must have same parity. If any one of $c, d$ has same parity as that of $a$, then its sum with $a$ gives an even number, which is impossible. Hence $c, d$ must have same parity, in which case $c+d(\bmod 10)$ is even, which leads to a contradiction. We conclude that $|S| \geq 5$.

|

5

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $X=\{0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}$. Let $S \subseteq X$ be such that any nonnegative integer $n$ can be written as $p+q$ where the nonnegative integers $p, q$ have all their digits in $S$. Find the smallest possible number of elements in $S$.

|

We show that 5 numbers will suffice. Take $S=\{0,1,3,4,6\}$. Observe the following splitting:

| $n$ | $a$ | $b$ |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | 1 | 4 |

| 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | 4 | 4 |

| 9 | 3 | 6 |

Thus each digit in a given nonnegative integer is split according to the above and can be written as a sum of two numbers each having digits in $S$.

We show that $|S|>4$. Suppose $|S| \leq 4$. We may take $|S|=4$ as adding extra numbers to $S$ does not alter our argument. Let $S=\{a, b, c, d\}$. Since the last digit can be any one of the numbers $0,1,2, \ldots, 9$, we must be able to write this as a sum of digits from $S$, modulo 10. Thus the collection

$$

A=\{x+y \quad(\bmod 10) \mid x, y \in S\}

$$

must contain $\{0,1,2, \ldots, 9\}$ as a subset. But $A$ has at most 10 elements $\left(\binom{4}{2}+4\right)$. Thus each element of the form $x+y(\bmod 10)$, as $x, y$ vary over $S$, must give different numbers from $\{0,1,2, \ldots, 9\}$.

Consider $a+a, b+b, c+c, d+d$ modulo 10. They must give 4 even numbers. Hence the remaining even number must be from the remaining 6 elements obtained by adding two distinct members of $S$. We may assume that even number is $a+b(\bmod 10)$. Then $a, b$ must have same parity. If any one of $c, d$ has same parity as that of $a$, then its sum with $a$ gives an even number, which is impossible. Hence $c, d$ must have same parity, in which case $c+d(\bmod 10)$ is even, which leads to a contradiction. We conclude that $|S| \geq 5$.

|

{

"resource_path": "INMO/segmented/en-sol-inmo-20.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:"

}

|

5b35f95a-e104-54a8-a6ed-6dbfbf25a349

| 607,904

|

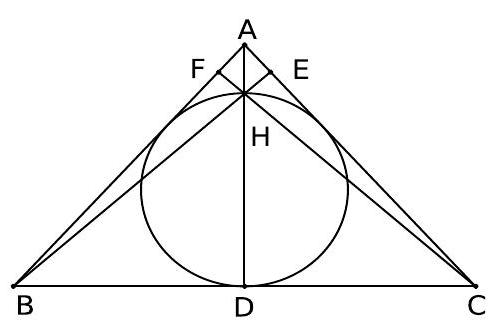

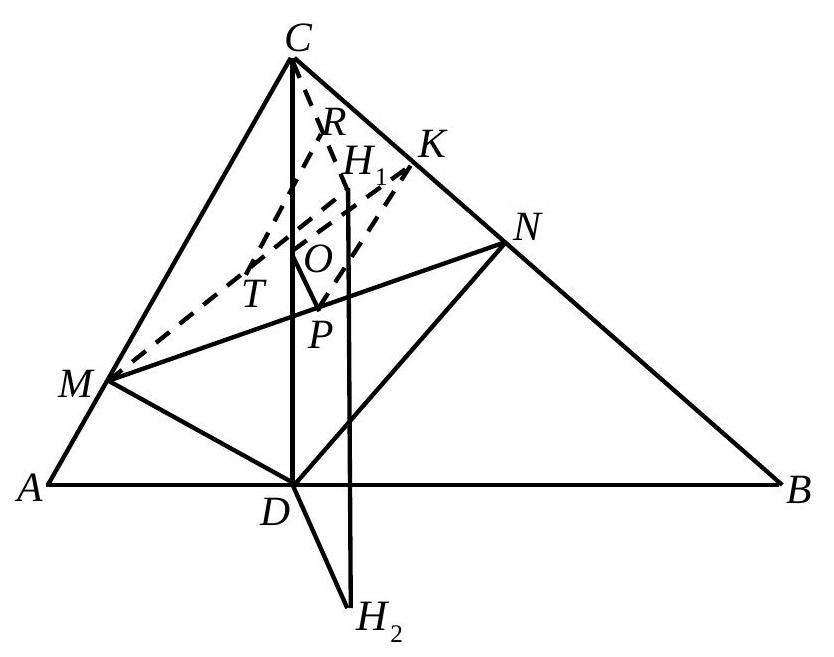

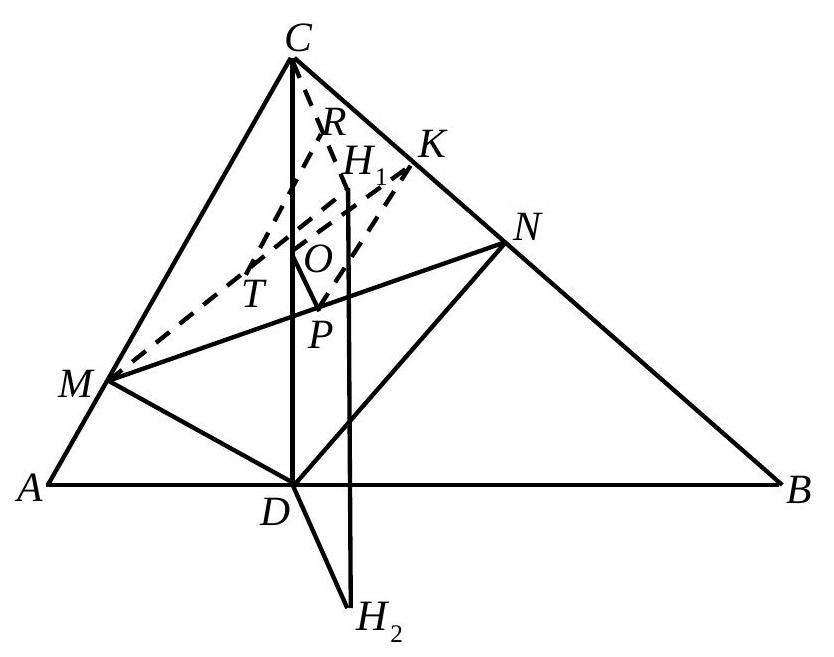

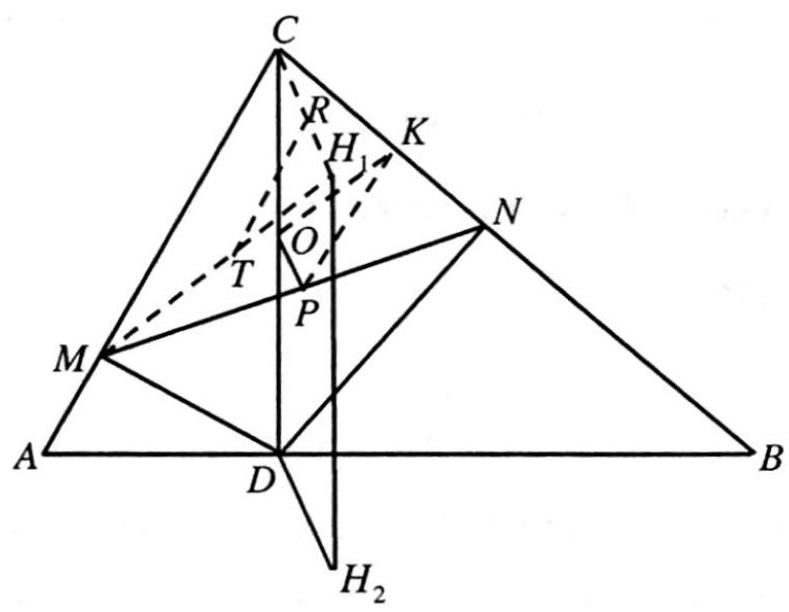

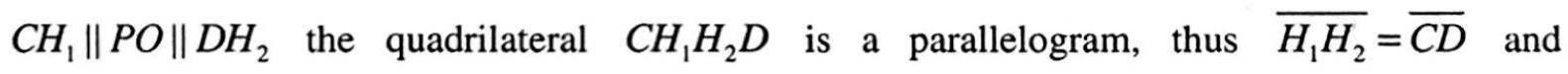

Let $A B C$ be triangle in which $A B=A C$. Suppose the orthocentre of the triangle lies on the in-circle. Find the ratio $A B / B C$.

|

Since the triangle is isosceles, the orthocentre lies on the perpendicular $A D$ from $A$ on to $B C$. Let it cut the in-circle at $H$. Now we are given that $H$ is the orthocentre of the triangle. Let $A B=A C=b$ and $B C=2 a$. Then $B D=a$. Observe that $b>a$ since $b$ is the hypotenuse and $a$ is a leg of a right-angled triangle. Let $B H$ meet $A C$ in $E$ and $C H$ meet $A B$ in $F$. By Pythagoras theorem applied to $\triangle B D H$, we get

$$

B H^{2}=H D^{2}+B D^{2}=4 r^{2}+a^{2}

$$

where $r$ is the in-radius of $A B C$. We want to compute $B H$ in another way. Since $A, F, H, E$ are con-cyclic, we have

$$

B H \cdot B E=B F \cdot B A

$$

But $B F \cdot B A=B D \cdot B C=2 a^{2}$, since $A, F, D, C$ are con-cyclic. Hence $B H^{2}=4 a^{4} / B E^{2}$. But

$$

B E^{2}=4 a^{2}-C E^{2}=4 a^{2}-B F^{2}=4 a^{2}-\left(\frac{2 a^{2}}{b}\right)^{2}=\frac{4 a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)}{b^{2}}

$$

This leads to

$$

B H^{2}=\frac{a^{2} b^{2}}{b^{2}-a^{2}}

$$

Thus we get

$$

\frac{a^{2} b^{2}}{b^{2}-a^{2}}=a^{2}+4 r^{2}

$$

This simplifies to $\left(a^{4} /\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)\right)=4 r^{2}$. Now we relate $a, b, r$ in another way using area. We know that $[A B C]=r s$, where $s$ is the semi-perimeter of $A B C$. We have $s=(b+b+2 a) / 2=b+a$. On the other hand area can be calculated using Heron's formula::

$$

[A B C]^{2}=s(s-2 a)(s-b)(s-b)=(b+a)(b-a) a^{2}=a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)

$$

Hence

$$

r^{2}=\frac{[A B C]^{2}}{s^{2}}=\frac{a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)}{(b+a)^{2}}

$$

Using this we get

$$

\frac{a^{4}}{b^{2}-a^{2}}=4\left(\frac{a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)}{(b+a)^{2}}\right)

$$

Therefore $a^{2}=4(b-a)^{2}$, which gives $a=2(b-a)$ or $2 b=3 a$. Finally,

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{b}{2 a}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

## Alternate Solution 1:

We use the known facts $B H=2 R \cos B$ and $r=4 R \sin (A / 2) \sin (B / 2) \sin (C / 2)$, where $R$ is the circumradius of $\triangle A B C$ and $r$ its in-radius. Therefore

$$

H D=B H \sin \angle H B D=2 R \cos B \sin \left(\frac{\pi}{2}-C\right)=2 R \cos ^{2} B

$$

since $\angle C=\angle B$. But $\angle B=(\pi-\angle A) / 2$, since $A B C$ is isosceles. Thus we obtain

$$

H D=2 R \cos ^{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{A}{2}\right)

$$

However $H D$ is also the diameter of the in circle. Therefore $H D=2 r$. Thus we get

$$

2 R \cos ^{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{A}{2}\right)=2 r=8 R \sin (A / 2) \sin ^{2}((\pi-A) / 4)

$$

This reduces to

$$

\sin (A / 2)=2(1-\sin (A / 2))

$$

Therefore $\sin (A / 2)=2 / 3$. We also observe that $\sin (A / 2)=B D / A B$. Finally

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{A B}{2 B D}=\frac{1}{2 \sin (A / 2)}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

## Alternate Solution 2:

Let $D$ be the mid-point of $B C$. Extend $A D$ to meet the circumcircle in $L$. Then we know that $H D=D L$. But $H D=2 r$. Thus $D L=2 r$. Therefore $I L=I D+D L=r+2 r=3 r$. We also know that $L B=L I$. Therefore $L B=3 r$. This gives

$$

\frac{B L}{L D}=\frac{3 r}{2 r}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

But $\triangle B L D$ is similar to $\triangle A B D$. So

$$

\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{B L}{L D}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

Finally,

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{A B}{2 B D}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

## Alternate Solution 3:

Let $D$ be the mid-point of $B C$ and $E$ be the mid-point of $D C$. Since $D I=I H(=r)$ and $D E=E C$, the mid-point theorem implies that $I E \| C H$. But $C H \perp A B$. Therefore $E I \perp A B$. Let $E I$ meet $A B$ in $F$. Then $F$ is the point of tangency of the incircle of $\triangle A B C$ with $A B$. Since the incircle is also tangent to $B C$ at $D$, we have $B F=B D$. Observe that $\triangle B F E$ is similar to $\triangle B D A$. Hence

$$

\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{B E}{B F}=\frac{B E}{B D}=\frac{B D+D E}{B D}=1+\frac{D E}{B D}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

This gives

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

|

\frac{3}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be triangle in which $A B=A C$. Suppose the orthocentre of the triangle lies on the in-circle. Find the ratio $A B / B C$.

|

Since the triangle is isosceles, the orthocentre lies on the perpendicular $A D$ from $A$ on to $B C$. Let it cut the in-circle at $H$. Now we are given that $H$ is the orthocentre of the triangle. Let $A B=A C=b$ and $B C=2 a$. Then $B D=a$. Observe that $b>a$ since $b$ is the hypotenuse and $a$ is a leg of a right-angled triangle. Let $B H$ meet $A C$ in $E$ and $C H$ meet $A B$ in $F$. By Pythagoras theorem applied to $\triangle B D H$, we get

$$

B H^{2}=H D^{2}+B D^{2}=4 r^{2}+a^{2}

$$

where $r$ is the in-radius of $A B C$. We want to compute $B H$ in another way. Since $A, F, H, E$ are con-cyclic, we have

$$

B H \cdot B E=B F \cdot B A

$$

But $B F \cdot B A=B D \cdot B C=2 a^{2}$, since $A, F, D, C$ are con-cyclic. Hence $B H^{2}=4 a^{4} / B E^{2}$. But

$$

B E^{2}=4 a^{2}-C E^{2}=4 a^{2}-B F^{2}=4 a^{2}-\left(\frac{2 a^{2}}{b}\right)^{2}=\frac{4 a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)}{b^{2}}

$$

This leads to

$$

B H^{2}=\frac{a^{2} b^{2}}{b^{2}-a^{2}}

$$

Thus we get

$$

\frac{a^{2} b^{2}}{b^{2}-a^{2}}=a^{2}+4 r^{2}

$$

This simplifies to $\left(a^{4} /\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)\right)=4 r^{2}$. Now we relate $a, b, r$ in another way using area. We know that $[A B C]=r s$, where $s$ is the semi-perimeter of $A B C$. We have $s=(b+b+2 a) / 2=b+a$. On the other hand area can be calculated using Heron's formula::

$$

[A B C]^{2}=s(s-2 a)(s-b)(s-b)=(b+a)(b-a) a^{2}=a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)

$$

Hence

$$

r^{2}=\frac{[A B C]^{2}}{s^{2}}=\frac{a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)}{(b+a)^{2}}

$$

Using this we get

$$

\frac{a^{4}}{b^{2}-a^{2}}=4\left(\frac{a^{2}\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)}{(b+a)^{2}}\right)

$$

Therefore $a^{2}=4(b-a)^{2}$, which gives $a=2(b-a)$ or $2 b=3 a$. Finally,

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{b}{2 a}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

## Alternate Solution 1:

We use the known facts $B H=2 R \cos B$ and $r=4 R \sin (A / 2) \sin (B / 2) \sin (C / 2)$, where $R$ is the circumradius of $\triangle A B C$ and $r$ its in-radius. Therefore

$$

H D=B H \sin \angle H B D=2 R \cos B \sin \left(\frac{\pi}{2}-C\right)=2 R \cos ^{2} B

$$

since $\angle C=\angle B$. But $\angle B=(\pi-\angle A) / 2$, since $A B C$ is isosceles. Thus we obtain

$$

H D=2 R \cos ^{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{A}{2}\right)

$$

However $H D$ is also the diameter of the in circle. Therefore $H D=2 r$. Thus we get

$$

2 R \cos ^{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{A}{2}\right)=2 r=8 R \sin (A / 2) \sin ^{2}((\pi-A) / 4)

$$

This reduces to

$$

\sin (A / 2)=2(1-\sin (A / 2))

$$

Therefore $\sin (A / 2)=2 / 3$. We also observe that $\sin (A / 2)=B D / A B$. Finally

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{A B}{2 B D}=\frac{1}{2 \sin (A / 2)}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

## Alternate Solution 2:

Let $D$ be the mid-point of $B C$. Extend $A D$ to meet the circumcircle in $L$. Then we know that $H D=D L$. But $H D=2 r$. Thus $D L=2 r$. Therefore $I L=I D+D L=r+2 r=3 r$. We also know that $L B=L I$. Therefore $L B=3 r$. This gives

$$

\frac{B L}{L D}=\frac{3 r}{2 r}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

But $\triangle B L D$ is similar to $\triangle A B D$. So

$$

\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{B L}{L D}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

Finally,

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{A B}{2 B D}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

## Alternate Solution 3:

Let $D$ be the mid-point of $B C$ and $E$ be the mid-point of $D C$. Since $D I=I H(=r)$ and $D E=E C$, the mid-point theorem implies that $I E \| C H$. But $C H \perp A B$. Therefore $E I \perp A B$. Let $E I$ meet $A B$ in $F$. Then $F$ is the point of tangency of the incircle of $\triangle A B C$ with $A B$. Since the incircle is also tangent to $B C$ at $D$, we have $B F=B D$. Observe that $\triangle B F E$ is similar to $\triangle B D A$. Hence

$$

\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{B E}{B F}=\frac{B E}{B D}=\frac{B D+D E}{B D}=1+\frac{D E}{B D}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

This gives

$$

\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{3}{4}

$$

|

{

"resource_path": "INMO/segmented/en-sol-inmo16.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:"

}

|

1dae100a-b4dc-5363-adfa-08d97515f883

| 607,908

|

Find the number of triples $(x, a, b)$ where $x$ is a real number and $a, b$ belong to the set $\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}$ such that

$$

x^{2}-a\{x\}+b=0

$$

where $\{x\}$ denotes the fractional part of the real number $x$. (For example $\{1.1\}=0.1=$ $\{-0.9\}$.

|

Let us write $x=n+f$ where $n=[x]$ and $f=\{x\}$. Then

$$

f^{2}+(2 n-a) f+n^{2}+b=0

$$

Observe that the product of the roots of (1) is $n^{2}+b \geq 1$. If this equation has to have a solution $0 \leq f<1$, the larger root of (1) is greater 1 . We conclude that the equation (1) has a real root less than 1 only if $P(1)<0$ where $P(y)=y^{2}+(2 n-a) y+n^{2}+2 b$. This gives

$$

1+2 n-a+n^{2}+2 b<0

$$

Therefore we have $(n+1)^{2}+b<a$. If $n \geq 2$, then $(n+1)^{2}+b \geq 10>a$. Hence $n \leq 1$. If $n \leq-4$, then again $(n+1)^{2}+b \geq 10>a$. Thus we have the range for $n:-3,-2,-1,0,1$. If $n=-3$ or $n=1$, we have $(n+1)^{2}=4$. Thus we must have $4+b<a$. If $a=9$, we must have $b=4,3,2,1$ giving 4 values. For $a=8$, we must have $b=3,2,1$ giving 3 values. Similarly, for $a=7$ we get 2 values of $b$ and $a=6$ leads to 1 value of $b$. In each case we get a real value of $f<1$ and this leads to a solution for $x$. Thus we get totally $2(4+3+2+1)=20$ values of the triple $(x, a, b)$.

For $n=-2$ and $n=0$, we have $(n+1)^{2}=1$. Hence we require $1+b<a$. We again count pairs $(a, b)$ such that $a-b>1$. For $a=9$, we get 7 values of $b$; for $a=8$ we get 6 values of $b$ and so on. Thus we get $2(7+6+5+4+3+2+1)=56$ values for the triple $(x, a, b)$.

Suppose $n=-1$ so that $(n+1)^{2}=0$. In this case we require $b<a$. We get $8+7+6+5+$ $4+3+2+1=36$ values for the triple $(x, a, b)$.

Thus the total number of triples $(x, a, b)$ is $20+56+36=112$.

|

112

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Find the number of triples $(x, a, b)$ where $x$ is a real number and $a, b$ belong to the set $\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}$ such that

$$

x^{2}-a\{x\}+b=0

$$

where $\{x\}$ denotes the fractional part of the real number $x$. (For example $\{1.1\}=0.1=$ $\{-0.9\}$.

|

Let us write $x=n+f$ where $n=[x]$ and $f=\{x\}$. Then

$$

f^{2}+(2 n-a) f+n^{2}+b=0

$$

Observe that the product of the roots of (1) is $n^{2}+b \geq 1$. If this equation has to have a solution $0 \leq f<1$, the larger root of (1) is greater 1 . We conclude that the equation (1) has a real root less than 1 only if $P(1)<0$ where $P(y)=y^{2}+(2 n-a) y+n^{2}+2 b$. This gives

$$

1+2 n-a+n^{2}+2 b<0

$$

Therefore we have $(n+1)^{2}+b<a$. If $n \geq 2$, then $(n+1)^{2}+b \geq 10>a$. Hence $n \leq 1$. If $n \leq-4$, then again $(n+1)^{2}+b \geq 10>a$. Thus we have the range for $n:-3,-2,-1,0,1$. If $n=-3$ or $n=1$, we have $(n+1)^{2}=4$. Thus we must have $4+b<a$. If $a=9$, we must have $b=4,3,2,1$ giving 4 values. For $a=8$, we must have $b=3,2,1$ giving 3 values. Similarly, for $a=7$ we get 2 values of $b$ and $a=6$ leads to 1 value of $b$. In each case we get a real value of $f<1$ and this leads to a solution for $x$. Thus we get totally $2(4+3+2+1)=20$ values of the triple $(x, a, b)$.

For $n=-2$ and $n=0$, we have $(n+1)^{2}=1$. Hence we require $1+b<a$. We again count pairs $(a, b)$ such that $a-b>1$. For $a=9$, we get 7 values of $b$; for $a=8$ we get 6 values of $b$ and so on. Thus we get $2(7+6+5+4+3+2+1)=56$ values for the triple $(x, a, b)$.

Suppose $n=-1$ so that $(n+1)^{2}=0$. In this case we require $b<a$. We get $8+7+6+5+$ $4+3+2+1=36$ values for the triple $(x, a, b)$.

Thus the total number of triples $(x, a, b)$ is $20+56+36=112$.

|

{

"resource_path": "INMO/segmented/en-sol-inmo_17.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:"

}

|

584c287f-af14-58ab-9d16-9b8690b56364

| 607,916

|

There are given 100 distinct positive integers. We call a pair of integers among them good if the ratio of its elements is either 2 or 3 . What is the maximum number $g$ of good pairs that these 100 numbers can form? (A same number can be used in several pairs.)

|

Like so often in Russian problems, numbers are used instead of generic symbols. Let us therefore denote $10=n>1,2=k>1,3=\ell>1$, with the extra condition both $k$ and $\ell$ aren't powers of a same number. Consider the digraph $G$ whose set of vertices $V(G)$ is made of $v=n^{2}$ distinct positive integers, and whose set of edges $E(G)$ is made by the pairs $(a, b) \in V(G) \times V(G)$ with $a \mid b$. For each positive integer $m$ consider now the (not induced) spanning subdigraph $G_{m}$ of $G$ (with $V\left(G_{m}\right)=V(G)$ and so $v_{m}=v=n^{2}$ vertices), and whose edges are the pairs $(a, b) \in G \times G$ with $b=m a$. Moreover, it is clear that $E\left(G_{m^{\prime}}\right) \cap E\left(G_{m^{\prime \prime}}\right)=\emptyset$ for $m^{\prime} \neq m^{\prime \prime}$ (since if $(a, b) \in E(G)$ then $(a, b) \in E\left(G_{b / a}\right)$ only), and also $\bigcup_{m \geq 1} E\left(G_{m}\right)=E(G)$ (but that is irrelevant). Since the good pairs are precisely the edges of $G_{k}$ and $G_{\ell}$ together, we need to maximize their number $g$.

A digraph $G_{m}$ is clearly a union of some $n_{m}$ disjoint (directed) paths $P_{m, i}$, with lengths $\lambda\left(P_{m, i}\right)=\lambda_{m, i}, 0 \leq \lambda_{m, i} \leq n^{2}-1$, such that $\sum_{i=1}^{n_{m}}\left(\lambda_{m, i}+1\right)=n^{2}$, and containing $e_{m}=\sum_{i=1}^{n_{m}} \lambda_{m, i}$ edges (zero-length paths, i.e. isolated vertices, are possible, allowed, and duly considered). The defect of the graph $G_{m}$ is taken to be $v-e_{m}=n_{m}$. We therefore need to maximize $g=e_{k}+e_{\ell}$, or equivalently, to minimize the defect $\delta=n_{k}+n_{\ell}$.

Using the model $V(G)=V_{x}=\left\{k^{i-1} \ell^{j-1} x \mid 1 \leq i, j \leq n\right\}$, we have $n_{k}=n_{\ell}=n$, therefore $\delta=2 n$, so $g=2 n(n-1)$. To prove value $2 n$ is a minimum for $\delta$ is almost obvious. We have $\lambda_{k, i} \leq n_{\ell}-1$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n_{k}$ (by the condition on $k$ and $\ell$, we have $\left|P_{k, i} \cap P_{\ell, j}\right| \leq 1$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n_{k}$ and $\left.1 \leq j \leq n_{\ell}\right),{ }^{2}$ so $n^{2}-n_{k}=e_{k}=\sum_{i=1}^{n_{k}} \lambda_{k, i} \leq \sum_{i=1}^{n_{k}}\left(n_{\ell}-1\right)=n_{k} n_{\ell}-n_{k}$, therefore $n^{2} \leq n_{k} n_{\ell}$, and so $\delta=n_{k}+n_{\ell} \geq 2 \sqrt{n_{k} n_{\ell}}=2 n$. Moreover, we see equality occurs if and only if $n_{k}=n_{\ell}=n$ and $\lambda_{k, i}=\lambda_{\ell, i}=n-1$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n$, thus only for the sets $V_{x}$ described above. Răspunsul este deci $g=180$.

Comentarii. Odată ce ideea vine, problema este aproape trivială, cu detaliile tehnice fiind aproape "forţate". Valorile particulare folosite aruncă doar un văl de umbră asupra situaţiei de fapt (mai ales ocultul $100=10^{2}$ )! Laticea de divizibilitate a celor $n^{2}$ numere este considerată în mod natural, şi conduce la facila numărătoare de mai sus.[^1]

## Second Day - Solutions

|

180

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

There are given 100 distinct positive integers. We call a pair of integers among them good if the ratio of its elements is either 2 or 3 . What is the maximum number $g$ of good pairs that these 100 numbers can form? (A same number can be used in several pairs.)

|

Like so often in Russian problems, numbers are used instead of generic symbols. Let us therefore denote $10=n>1,2=k>1,3=\ell>1$, with the extra condition both $k$ and $\ell$ aren't powers of a same number. Consider the digraph $G$ whose set of vertices $V(G)$ is made of $v=n^{2}$ distinct positive integers, and whose set of edges $E(G)$ is made by the pairs $(a, b) \in V(G) \times V(G)$ with $a \mid b$. For each positive integer $m$ consider now the (not induced) spanning subdigraph $G_{m}$ of $G$ (with $V\left(G_{m}\right)=V(G)$ and so $v_{m}=v=n^{2}$ vertices), and whose edges are the pairs $(a, b) \in G \times G$ with $b=m a$. Moreover, it is clear that $E\left(G_{m^{\prime}}\right) \cap E\left(G_{m^{\prime \prime}}\right)=\emptyset$ for $m^{\prime} \neq m^{\prime \prime}$ (since if $(a, b) \in E(G)$ then $(a, b) \in E\left(G_{b / a}\right)$ only), and also $\bigcup_{m \geq 1} E\left(G_{m}\right)=E(G)$ (but that is irrelevant). Since the good pairs are precisely the edges of $G_{k}$ and $G_{\ell}$ together, we need to maximize their number $g$.

A digraph $G_{m}$ is clearly a union of some $n_{m}$ disjoint (directed) paths $P_{m, i}$, with lengths $\lambda\left(P_{m, i}\right)=\lambda_{m, i}, 0 \leq \lambda_{m, i} \leq n^{2}-1$, such that $\sum_{i=1}^{n_{m}}\left(\lambda_{m, i}+1\right)=n^{2}$, and containing $e_{m}=\sum_{i=1}^{n_{m}} \lambda_{m, i}$ edges (zero-length paths, i.e. isolated vertices, are possible, allowed, and duly considered). The defect of the graph $G_{m}$ is taken to be $v-e_{m}=n_{m}$. We therefore need to maximize $g=e_{k}+e_{\ell}$, or equivalently, to minimize the defect $\delta=n_{k}+n_{\ell}$.

Using the model $V(G)=V_{x}=\left\{k^{i-1} \ell^{j-1} x \mid 1 \leq i, j \leq n\right\}$, we have $n_{k}=n_{\ell}=n$, therefore $\delta=2 n$, so $g=2 n(n-1)$. To prove value $2 n$ is a minimum for $\delta$ is almost obvious. We have $\lambda_{k, i} \leq n_{\ell}-1$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n_{k}$ (by the condition on $k$ and $\ell$, we have $\left|P_{k, i} \cap P_{\ell, j}\right| \leq 1$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n_{k}$ and $\left.1 \leq j \leq n_{\ell}\right),{ }^{2}$ so $n^{2}-n_{k}=e_{k}=\sum_{i=1}^{n_{k}} \lambda_{k, i} \leq \sum_{i=1}^{n_{k}}\left(n_{\ell}-1\right)=n_{k} n_{\ell}-n_{k}$, therefore $n^{2} \leq n_{k} n_{\ell}$, and so $\delta=n_{k}+n_{\ell} \geq 2 \sqrt{n_{k} n_{\ell}}=2 n$. Moreover, we see equality occurs if and only if $n_{k}=n_{\ell}=n$ and $\lambda_{k, i}=\lambda_{\ell, i}=n-1$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n$, thus only for the sets $V_{x}$ described above. Răspunsul este deci $g=180$.

Comentarii. Odată ce ideea vine, problema este aproape trivială, cu detaliile tehnice fiind aproape "forţate". Valorile particulare folosite aruncă doar un văl de umbră asupra situaţiei de fapt (mai ales ocultul $100=10^{2}$ )! Laticea de divizibilitate a celor $n^{2}$ numere este considerată în mod natural, şi conduce la facila numărătoare de mai sus.[^1]

## Second Day - Solutions

|

{

"resource_path": "IZho/segmented/en-2014_zhautykov_resenja_e.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

|

cccb2214-f230-5016-bc1e-467d2a7603ec

| 604,188

|

Determine the maximum integer $n$ with the property that for each positive integer $k \leq \frac{n}{2}$ there exist two positive divisors of $n$ with difference $k$.

|

If there exists a positive integer $p \leq\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$ such that $p \nmid n$, then we have $\lfloor n / 2\rfloor>\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$, and taking $k=\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p \geq 2$ and two positive divisors $d, d+k$ of $n$, we need $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p)$ to divide $n$. But $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p) \geq d+\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-\lfloor n / 6\rfloor>d+(n / 2-1)-n / 6 \geq n / 3$, so $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p) \in\{n / 2, n\}$, the only possible divisors of $n$ larger than $n / 3$. However, $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p)=n / 2$ yields $d=p$, absurd (since $d \mid n$ but $p \nmid n$ ), while $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p)=n$ yields $d>n / 2$, thus $d=n$ (since $d \mid n$ ), forcing $p=\lfloor n / 2\rfloor>\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$, again absurd. Therefore all positive integers not larger than $\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$ must divide $n$.

Denote $u=\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$. Since $\operatorname{gcd}(u, u-1)=1$, it follows $u(u-1) \mid n$, so $u(u-1) \leq n=6(n / 6)<6(u+1)$, forcing $u \leq 7$. For $u \geq 4$ we need $\operatorname{lcm}[1,2,3,4]=12 \mid n$, and we can see that $n=24$ satisfies, and moreover is an acceptable value. For $n=36$ we get $u=6$, but $\operatorname{lcm}[1,2,3,4,5,6]=60 \nmid n$. And for $n \geq 48$ we have $u \geq 8$, not acceptable. Thus the answer is $n=24$.

We may in fact quite easily exhibit the full set $\{1,2,4,6,8,12,18,24\}$ of such positive integers $n$ (for $n=1$ the condition is vacuously fulfilled). The related question of which are the positive integers satisfying the above property for all $1 \leq k \leq n-1$ can also easily be answered; the full set is $\{1,2,4,6\}$.

Comentarii. O problemă extrem de drăguţă, şi nu tocmai simplă dacă ne străduim să evităm discutarea a prea multe cazuri. Analiza numerelor $n$ mici ne sugerează imediat că $n>1$ nu poate să fie impar (ceea ce este trivial), şi prin faptul că singurul $k$ defect pentru $n=36$ este $k=13$, ideea pentru soluţia dată mai sus. Oricum, o idee proaspătă, şi care se implementează elegant şi cu calcule minime.

|

24

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Determine the maximum integer $n$ with the property that for each positive integer $k \leq \frac{n}{2}$ there exist two positive divisors of $n$ with difference $k$.

|

If there exists a positive integer $p \leq\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$ such that $p \nmid n$, then we have $\lfloor n / 2\rfloor>\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$, and taking $k=\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p \geq 2$ and two positive divisors $d, d+k$ of $n$, we need $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p)$ to divide $n$. But $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p) \geq d+\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-\lfloor n / 6\rfloor>d+(n / 2-1)-n / 6 \geq n / 3$, so $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p) \in\{n / 2, n\}$, the only possible divisors of $n$ larger than $n / 3$. However, $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p)=n / 2$ yields $d=p$, absurd (since $d \mid n$ but $p \nmid n$ ), while $d+(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor-p)=n$ yields $d>n / 2$, thus $d=n$ (since $d \mid n$ ), forcing $p=\lfloor n / 2\rfloor>\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$, again absurd. Therefore all positive integers not larger than $\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$ must divide $n$.

Denote $u=\lfloor n / 6\rfloor$. Since $\operatorname{gcd}(u, u-1)=1$, it follows $u(u-1) \mid n$, so $u(u-1) \leq n=6(n / 6)<6(u+1)$, forcing $u \leq 7$. For $u \geq 4$ we need $\operatorname{lcm}[1,2,3,4]=12 \mid n$, and we can see that $n=24$ satisfies, and moreover is an acceptable value. For $n=36$ we get $u=6$, but $\operatorname{lcm}[1,2,3,4,5,6]=60 \nmid n$. And for $n \geq 48$ we have $u \geq 8$, not acceptable. Thus the answer is $n=24$.

We may in fact quite easily exhibit the full set $\{1,2,4,6,8,12,18,24\}$ of such positive integers $n$ (for $n=1$ the condition is vacuously fulfilled). The related question of which are the positive integers satisfying the above property for all $1 \leq k \leq n-1$ can also easily be answered; the full set is $\{1,2,4,6\}$.

Comentarii. O problemă extrem de drăguţă, şi nu tocmai simplă dacă ne străduim să evităm discutarea a prea multe cazuri. Analiza numerelor $n$ mici ne sugerează imediat că $n>1$ nu poate să fie impar (ceea ce este trivial), şi prin faptul că singurul $k$ defect pentru $n=36$ este $k=13$, ideea pentru soluţia dată mai sus. Oricum, o idee proaspătă, şi care se implementează elegant şi cu calcule minime.

|

{

"resource_path": "IZho/segmented/en-2015_zhautykov_resenja_e.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 4.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

|

30c53e84-0548-56fb-9f55-dfd98e1ec71a

| 604,297

|

The Crocodile thought of four unit squares of a $2018 \times 2018$ forming a rectangle with sides 1 and 4 . The Bear can choose any square formed by 9 unit squares and ask whether it contains at least one of the four Crocodile's squares. What minimum number of questions should he ask to be sure of at least one affirmative answer?

The answer is $\frac{673^{2}-1}{2}=226464$.

|

We call checked any square chosen by the Bear, and all its unit squares. The position of a unit square in the table can be defined by the numbers of its row and column, that is, the square $(x, y)$ is in the $x$-th row and $y$-th column.

First we prove that $\frac{673^{2}-1}{2}$ questions is enough even on a $2019 \times 2019$ table. Let us divide this table into $3 \times 3$ squares and apply chess colouring to these large squares so that the corners are white. Thet it is enough to check all the black $3 \times 3$ squares: no row or column contains four consecutive white squares.

To prove that we need so many questions, we select all the unit squares with coordinates $(3 m+1,3 n+1)$, where $0 \leqslant m, n \leqslant 672$. A $3 \times 3$ square obviously can not contain two selected unit squares. On the other hand, if two selected squares lie at distance 3 (i.e., one of them is $(x, y)$, and another is $(x, y+3)$ or $(x+3, y)$ ), the Bear must check at least one of these two squares (because if neither is checked, then so are the two unit squares between them, and the Crocodile can place his rectangle on the unchecked squares).

Thus it is enough to produce $\frac{673^{2}-1}{2}$ pairs of selected unit squares at distance 3 . One can take pairs $(6 k+1,3 n+1)$, $(6 k+4,3 n+1), 0 \leqslant k \leqslant 335,0 \leqslant n \leqslant 672$, and $(2017,6 n+1),(2017,6 n+4), 0 \leqslant n \leqslant 335$.

|

226464

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

The Crocodile thought of four unit squares of a $2018 \times 2018$ forming a rectangle with sides 1 and 4 . The Bear can choose any square formed by 9 unit squares and ask whether it contains at least one of the four Crocodile's squares. What minimum number of questions should he ask to be sure of at least one affirmative answer?

The answer is $\frac{673^{2}-1}{2}=226464$.

|

We call checked any square chosen by the Bear, and all its unit squares. The position of a unit square in the table can be defined by the numbers of its row and column, that is, the square $(x, y)$ is in the $x$-th row and $y$-th column.

First we prove that $\frac{673^{2}-1}{2}$ questions is enough even on a $2019 \times 2019$ table. Let us divide this table into $3 \times 3$ squares and apply chess colouring to these large squares so that the corners are white. Thet it is enough to check all the black $3 \times 3$ squares: no row or column contains four consecutive white squares.

To prove that we need so many questions, we select all the unit squares with coordinates $(3 m+1,3 n+1)$, where $0 \leqslant m, n \leqslant 672$. A $3 \times 3$ square obviously can not contain two selected unit squares. On the other hand, if two selected squares lie at distance 3 (i.e., one of them is $(x, y)$, and another is $(x, y+3)$ or $(x+3, y)$ ), the Bear must check at least one of these two squares (because if neither is checked, then so are the two unit squares between them, and the Crocodile can place his rectangle on the unchecked squares).

Thus it is enough to produce $\frac{673^{2}-1}{2}$ pairs of selected unit squares at distance 3 . One can take pairs $(6 k+1,3 n+1)$, $(6 k+4,3 n+1), 0 \leqslant k \leqslant 335,0 \leqslant n \leqslant 672$, and $(2017,6 n+1),(2017,6 n+4), 0 \leqslant n \leqslant 335$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IZho/segmented/en-2018_zhautykov_resenja_e.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

|

70dc1bbb-4d68-55cb-a420-31a2790b116b

| 604,358

|

In a set of 20 elements there are $2 k+1$ different subsets of 7 elements such that each of these subsets intersects exactly $k$ other subsets. Find the maximum $k$ for which this is possible.

The answer is $k=2$.

|

Let $M$ be the set of residues mod20. An example is given by the sets $A_{i}=\{4 i+1,4 i+$ $2,4 i+3,4 i+4,4 i+5,4 i+6,4 i+7\} \subset M, i=0,1,2,3,4$.

Let $k \geq 2$. Obviously among any three 7-element subsets there are two intersecting subsets.

Let $A$ be any of the $2 k+1$ subsets. It intersects $k$ other subsets $B_{1}, \ldots, B_{k}$. The remaining subsets $C_{1}$, $\ldots, C_{k}$ do not intersect $A$ and are therefore pairwise intersecting. Since each $C_{i}$ intersects $k$ other subsets, it intersects exactly one $B_{j}$. This $B_{j}$ can not be the same for all $C_{i}$ because $B_{j}$ can not intersect $k+1$ subsets.

Thus there are two different $C_{i}$ intersecting different $B_{j}$; let $C_{1}$ intersect $B_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ intersect $B_{2}$. All the subsets that do not intersect $C_{1}$ must intersect each other; there is $A$ among them, therefore they are $A$ and all $B_{i}, i \neq 1$. Hence every $B_{j}$ and $B_{j}, i \neq 1, j \neq 1$, intersect. Applying the same argument to $C_{2}$ we see that any $B_{i}$ and $B_{j}, i \neq 2, j \neq 2$, intersect. We see that the family $A, B_{1}, \ldots, B_{k}$ contains only one pair, $B_{1}$ and $B_{2}$, of non-untersecting subsets, while $B_{1}$ intersects $C_{1}$ and $B_{2}$ intersects $C_{2}$. For each $i$ this list contains $k$ subsets intersecting $B_{i}$. It follows that no $C_{i}$ with $i>2$ intersects any $B_{j}$, that is, there are no such $C_{i}$, and $k \leq 2$.

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In a set of 20 elements there are $2 k+1$ different subsets of 7 elements such that each of these subsets intersects exactly $k$ other subsets. Find the maximum $k$ for which this is possible.

The answer is $k=2$.

|

Let $M$ be the set of residues mod20. An example is given by the sets $A_{i}=\{4 i+1,4 i+$ $2,4 i+3,4 i+4,4 i+5,4 i+6,4 i+7\} \subset M, i=0,1,2,3,4$.

Let $k \geq 2$. Obviously among any three 7-element subsets there are two intersecting subsets.

Let $A$ be any of the $2 k+1$ subsets. It intersects $k$ other subsets $B_{1}, \ldots, B_{k}$. The remaining subsets $C_{1}$, $\ldots, C_{k}$ do not intersect $A$ and are therefore pairwise intersecting. Since each $C_{i}$ intersects $k$ other subsets, it intersects exactly one $B_{j}$. This $B_{j}$ can not be the same for all $C_{i}$ because $B_{j}$ can not intersect $k+1$ subsets.

Thus there are two different $C_{i}$ intersecting different $B_{j}$; let $C_{1}$ intersect $B_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ intersect $B_{2}$. All the subsets that do not intersect $C_{1}$ must intersect each other; there is $A$ among them, therefore they are $A$ and all $B_{i}, i \neq 1$. Hence every $B_{j}$ and $B_{j}, i \neq 1, j \neq 1$, intersect. Applying the same argument to $C_{2}$ we see that any $B_{i}$ and $B_{j}, i \neq 2, j \neq 2$, intersect. We see that the family $A, B_{1}, \ldots, B_{k}$ contains only one pair, $B_{1}$ and $B_{2}$, of non-untersecting subsets, while $B_{1}$ intersects $C_{1}$ and $B_{2}$ intersects $C_{2}$. For each $i$ this list contains $k$ subsets intersecting $B_{i}$. It follows that no $C_{i}$ with $i>2$ intersects any $B_{j}$, that is, there are no such $C_{i}$, and $k \leq 2$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IZho/segmented/en-2020_zhautykov_resenja_e.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

|

38364def-1c4d-5c64-828c-3bb7af51fd1a

| 604,498

|

Some squares of a $n \times n$ table $(n>2)$ are black, the rest are white. In every white square we write the number of all the black squares having at least one common vertex with it. Find the maximum possible sum of all these numbers.

The answer is $3 n^{2}-5 n+2$.

|

The sum attains this value when all squares in even rows are black and the rest are white. It remains to prove that this is the maximum value.

The sum in question is the number of pairs of differently coloured squares sharing at least one vertex. There are two kinds of such pairs: sharing a side and sharing only one vertex. Let us count the number of these pairs in another way.

We start with zeroes in all the vertices. Then for each pair of the second kind we add 1 to the (only) common vertex of this pair, and for each pair of the first kind we add $\frac{1}{2}$ to each of the two common vertices of its squares. For each pair the sum of all the numbers increases by 1 , therefore in the end it is equal to the number of pairs.

Simple casework shows that

(i) 3 is written in an internal vertex if and only if this vertex belongs to two black squares sharing a side and two white squares sharing a side;

(ii) the numbers in all the other internal vertices do not exceed 2 ;

(iii) a border vertex is marked with $\frac{1}{2}$ if it belongs to two squares of different colours, and 0 otherwise; (iv) all the corners are marked with 0 .

Note: we have already proved that the sum in question does not exceed $3 \times(n-1)^{2}+\frac{1}{2}(4 n-4)=$ $=3 n^{2}-4 n+1$. This estimate is valuable in itself.

Now we prove that the numbers in all the vertices can not be maximum possible simultaneously. To be more precise we need some definitions.

Definition. The number in a vertex is maximum if the vertex is internal and the number is 3 , or the vertex is on the border and the number is $\frac{1}{2}$.

Definition. A path - is a sequence of vertices such that every two consecutive vertices are one square side away.

Lemma. In each colouring of the table every path that starts on a horizontal side, ends on a vertical side and does not pass through corners, contains a number which is not maximum.

Proof. Assume the contrary. Then if the colour of any square containing the initial vertex is chosen, the colours of all the other squares containing the vertices of the path is uniquely defined, and the number in the last vertex is 0 .

Now we can prove that the sum of the numbers in any colouring does not exceed the sum of all the maximum numbers minus quarter of the number of all border vertices (not including corners). Consider the squares $1 \times 1,2 \times 2, \ldots,(N-1) \times(N-1)$ with a vertex in the lower left corner of the table. The right side and the upper side of such square form a path satisfying the conditions of the Lemma. Similar set of $N-1$ paths is produced by the squares $1 \times 1,2 \times 2, \ldots,(N-1) \times(N-1)$ with a vertex in the upper right corner of the table. Each border vertex is covered by one of these $2 n-2$ paths, and each internal vertex by two.

In any colouring of the table each of these paths contains a number which is not maximum. If this number is on the border, it is smaller than the maximum by (at least) $\frac{1}{2}$ and does not belong to any other path. If this number is in an internal vertex, it belongs to two paths and is smaller than the maximum at least by 1. Thus the contribution of each path in the sum in question is less than the maximum possible at least by $\frac{1}{2}$, q.e.d.

An interesting question: is it possible to count all the colourings with maximum sum using this argument?

|

3 n^{2}-5 n+2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Some squares of a $n \times n$ table $(n>2)$ are black, the rest are white. In every white square we write the number of all the black squares having at least one common vertex with it. Find the maximum possible sum of all these numbers.

The answer is $3 n^{2}-5 n+2$.

|

The sum attains this value when all squares in even rows are black and the rest are white. It remains to prove that this is the maximum value.

The sum in question is the number of pairs of differently coloured squares sharing at least one vertex. There are two kinds of such pairs: sharing a side and sharing only one vertex. Let us count the number of these pairs in another way.

We start with zeroes in all the vertices. Then for each pair of the second kind we add 1 to the (only) common vertex of this pair, and for each pair of the first kind we add $\frac{1}{2}$ to each of the two common vertices of its squares. For each pair the sum of all the numbers increases by 1 , therefore in the end it is equal to the number of pairs.

Simple casework shows that

(i) 3 is written in an internal vertex if and only if this vertex belongs to two black squares sharing a side and two white squares sharing a side;

(ii) the numbers in all the other internal vertices do not exceed 2 ;

(iii) a border vertex is marked with $\frac{1}{2}$ if it belongs to two squares of different colours, and 0 otherwise; (iv) all the corners are marked with 0 .

Note: we have already proved that the sum in question does not exceed $3 \times(n-1)^{2}+\frac{1}{2}(4 n-4)=$ $=3 n^{2}-4 n+1$. This estimate is valuable in itself.

Now we prove that the numbers in all the vertices can not be maximum possible simultaneously. To be more precise we need some definitions.

Definition. The number in a vertex is maximum if the vertex is internal and the number is 3 , or the vertex is on the border and the number is $\frac{1}{2}$.

Definition. A path - is a sequence of vertices such that every two consecutive vertices are one square side away.

Lemma. In each colouring of the table every path that starts on a horizontal side, ends on a vertical side and does not pass through corners, contains a number which is not maximum.

Proof. Assume the contrary. Then if the colour of any square containing the initial vertex is chosen, the colours of all the other squares containing the vertices of the path is uniquely defined, and the number in the last vertex is 0 .

Now we can prove that the sum of the numbers in any colouring does not exceed the sum of all the maximum numbers minus quarter of the number of all border vertices (not including corners). Consider the squares $1 \times 1,2 \times 2, \ldots,(N-1) \times(N-1)$ with a vertex in the lower left corner of the table. The right side and the upper side of such square form a path satisfying the conditions of the Lemma. Similar set of $N-1$ paths is produced by the squares $1 \times 1,2 \times 2, \ldots,(N-1) \times(N-1)$ with a vertex in the upper right corner of the table. Each border vertex is covered by one of these $2 n-2$ paths, and each internal vertex by two.

In any colouring of the table each of these paths contains a number which is not maximum. If this number is on the border, it is smaller than the maximum by (at least) $\frac{1}{2}$ and does not belong to any other path. If this number is in an internal vertex, it belongs to two paths and is smaller than the maximum at least by 1. Thus the contribution of each path in the sum in question is less than the maximum possible at least by $\frac{1}{2}$, q.e.d.

An interesting question: is it possible to count all the colourings with maximum sum using this argument?

|

{

"resource_path": "IZho/segmented/en-2020_zhautykov_resenja_e.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n№6.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

|

942431d0-f2bf-5b08-a166-6a6897dae34c

| 604,549

|

On a party with 99 guests, hosts Ann and Bob play a game (the hosts are not regarded as guests). There are 99 chairs arranged in a circle; initially, all guests hang around those chairs. The hosts take turns alternately. By a turn, a host orders any standing guest to sit on an unoccupied chair $c$. If some chair adjacent to $c$ is already occupied, the same host orders one guest on such chair to stand up (if both chairs adjacent to $c$ are occupied, the host chooses exactly one of them). All orders are carried out immediately. Ann makes the first move; her goal is to fulfill, after some move of hers, that at least $k$ chairs are occupied. Determine the largest $k$ for which Ann can reach the goal, regardless of Bob's play.

Answer. $k=34$.

|

Preliminary notes. Let $F$ denote the number of occupied chairs at the current position in the game. Notice that, on any turn, $F$ does not decrease. Thus, we need to determine the maximal value of $F$ Ann can guarantee after an arbitrary move (either hers or her opponent's).

Say that the situation in the game is stable if every unoccupied chair is adjacent to an occupied one. In a stable situation, we have $F \geq 33$, since at most $3 F$ chairs are either occupied or adjacent to such. Moreover, the same argument shows that there is a unique (up to rotation) stable situation with $F=33$, in which exactly every third chair is occupied; call such stable situation bad.

If the situation after Bob's move is stable, then Bob can act so as to preserve the current value of $F$ indefinitely. Namely, if $A$ puts some guest on chair $a$, she must free some chair $b$ adjacent to $a$. Then Bob merely puts a guest on $b$ and frees $a$, returning to the same stable position.

On the other hand, if the situation after Bob's move is unstable, then Ann may increase $F$ in her turn by putting a guest on a chair having no adjacent occupied chairs.

Strategy for Ann, if $k \leq 34$. In short, Ann's strategy is to increase $F$ avoiding appearance of a bad situation after Bob's move (conversely, Ann creates a bad situation in her turn, if she can).

So, on each her turn, Ann takes an arbitrary turn increasing $F$ if there is no danger that Bob reaches a bad situation in the next turn (thus, Ann always avoids forcing any guest to stand up). The exceptional cases are listed below.

Case 1. After possible Ann's move (consisting in putting a guest on chair $a$ ), we have $F=32$, and Bob can reach a bad situation by putting a guest on some chair. This means that, after Ann's move, every third chair would be occupied, with one exception. But this means that, by her move, Ann could put a guest on a chair adjacent to $a$, avoiding the danger.

Case 2. After possible Ann's move (by putting a guest on chair $a$ ), we have $F=33$, and Bob can reach a stable situation by putting a guest on some chair $b$ and freeing an adjacent chair $c$. If $a=c$, then Ann could put her guest on $b$ to create a stable situation after her turn; that enforces Bob to break stability in his turn. Otherwise, as in the previous case, Ann could put a guest on some chair adjacent to $a$, still increasing the value of $F$, but with no danger of bad situation arising.

So, acting as described, Ann increases the value of $F$ on each turn of hers whenever $F \leq 33$. Thus, she reaches $F=34$ after some her turn.

Strategy for Bob, if $k \geq 35$. Split all chairs into 33 groups each consisting of three consecutive chairs, and number the groups by $1,2, \ldots, 33$ so that Ann's first turn uses a chair from group 1. In short, Bob's strategy is to ensure, after each his turn, that

$(*)$ In group 1, at most two chairs are occupied; in every other group, only the central chair may be occupied.

If $(*)$ is satisfied after Bob's turn, then $F \leq 34<k$; thus, property $(*)$ ensures that Bob will not lose. It remains to show that Bob can always preserve $(*)$. after any his turn. Clearly, he can do that oat the first turn.

Suppose first that Ann, in her turn, puts a guest on chair $a$ and frees an adjacent chair $b$, then Bob may revert her turn by putting a guest on chair $b$ and freeing chair $a$.

Suppose now that Ann just puts a guest on some chair $a$, and the chairs adjacent to $a$ are unoccupied. In particular, group 1 still contains at most two occupied chairs. If the obtained situation satisfies (*), then Bob just makes a turn by putting a guest into group 1 (preferably, on its central chair), and, possibly, removing another guest from that group. Otherwise, $a$ is a non-central chair in some group $i \geq 2$; in this case Bob puts a guest to the central chair in group $i$ and frees chair $a$.

So Bob indeed can always preserve (*).

|

34

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

On a party with 99 guests, hosts Ann and Bob play a game (the hosts are not regarded as guests). There are 99 chairs arranged in a circle; initially, all guests hang around those chairs. The hosts take turns alternately. By a turn, a host orders any standing guest to sit on an unoccupied chair $c$. If some chair adjacent to $c$ is already occupied, the same host orders one guest on such chair to stand up (if both chairs adjacent to $c$ are occupied, the host chooses exactly one of them). All orders are carried out immediately. Ann makes the first move; her goal is to fulfill, after some move of hers, that at least $k$ chairs are occupied. Determine the largest $k$ for which Ann can reach the goal, regardless of Bob's play.

Answer. $k=34$.

|

Preliminary notes. Let $F$ denote the number of occupied chairs at the current position in the game. Notice that, on any turn, $F$ does not decrease. Thus, we need to determine the maximal value of $F$ Ann can guarantee after an arbitrary move (either hers or her opponent's).

Say that the situation in the game is stable if every unoccupied chair is adjacent to an occupied one. In a stable situation, we have $F \geq 33$, since at most $3 F$ chairs are either occupied or adjacent to such. Moreover, the same argument shows that there is a unique (up to rotation) stable situation with $F=33$, in which exactly every third chair is occupied; call such stable situation bad.

If the situation after Bob's move is stable, then Bob can act so as to preserve the current value of $F$ indefinitely. Namely, if $A$ puts some guest on chair $a$, she must free some chair $b$ adjacent to $a$. Then Bob merely puts a guest on $b$ and frees $a$, returning to the same stable position.

On the other hand, if the situation after Bob's move is unstable, then Ann may increase $F$ in her turn by putting a guest on a chair having no adjacent occupied chairs.

Strategy for Ann, if $k \leq 34$. In short, Ann's strategy is to increase $F$ avoiding appearance of a bad situation after Bob's move (conversely, Ann creates a bad situation in her turn, if she can).

So, on each her turn, Ann takes an arbitrary turn increasing $F$ if there is no danger that Bob reaches a bad situation in the next turn (thus, Ann always avoids forcing any guest to stand up). The exceptional cases are listed below.

Case 1. After possible Ann's move (consisting in putting a guest on chair $a$ ), we have $F=32$, and Bob can reach a bad situation by putting a guest on some chair. This means that, after Ann's move, every third chair would be occupied, with one exception. But this means that, by her move, Ann could put a guest on a chair adjacent to $a$, avoiding the danger.

Case 2. After possible Ann's move (by putting a guest on chair $a$ ), we have $F=33$, and Bob can reach a stable situation by putting a guest on some chair $b$ and freeing an adjacent chair $c$. If $a=c$, then Ann could put her guest on $b$ to create a stable situation after her turn; that enforces Bob to break stability in his turn. Otherwise, as in the previous case, Ann could put a guest on some chair adjacent to $a$, still increasing the value of $F$, but with no danger of bad situation arising.

So, acting as described, Ann increases the value of $F$ on each turn of hers whenever $F \leq 33$. Thus, she reaches $F=34$ after some her turn.

Strategy for Bob, if $k \geq 35$. Split all chairs into 33 groups each consisting of three consecutive chairs, and number the groups by $1,2, \ldots, 33$ so that Ann's first turn uses a chair from group 1. In short, Bob's strategy is to ensure, after each his turn, that

$(*)$ In group 1, at most two chairs are occupied; in every other group, only the central chair may be occupied.

If $(*)$ is satisfied after Bob's turn, then $F \leq 34<k$; thus, property $(*)$ ensures that Bob will not lose. It remains to show that Bob can always preserve $(*)$. after any his turn. Clearly, he can do that oat the first turn.

Suppose first that Ann, in her turn, puts a guest on chair $a$ and frees an adjacent chair $b$, then Bob may revert her turn by putting a guest on chair $b$ and freeing chair $a$.

Suppose now that Ann just puts a guest on some chair $a$, and the chairs adjacent to $a$ are unoccupied. In particular, group 1 still contains at most two occupied chairs. If the obtained situation satisfies (*), then Bob just makes a turn by putting a guest into group 1 (preferably, on its central chair), and, possibly, removing another guest from that group. Otherwise, $a$ is a non-central chair in some group $i \geq 2$; in this case Bob puts a guest to the central chair in group $i$ and frees chair $a$.

So Bob indeed can always preserve (*).

|

{

"resource_path": "IZho/segmented/en-2021_zhautykov_resenja_e.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n№5.",

"solution_match": "\nSolution."

}

|

e71b10cd-12d6-567c-81ec-37de86b7c2da

| 604,677

|

The function $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})$ is defined on the positive integers and takes non-negative integer values. It satisfies (1) $f(m n)=f(m)+f(n),(2) f(n)=0$ if the last digit of $n$ is 3 , (3) $f(10)=0$. Find $\mathrm{f}(1985)$.

|

If $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{mn})=0$, then $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{m})+\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})=0($ by $(1))$. But $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{m})$ and $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})$ are non-negative, so $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{m})=\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})=$ 0 . Thus $f(10)=0$ implies $f(5)=0$. Similarly $f(3573)=0$ by (2), so $f(397)=0$. Hence $f(1985)$ $=\mathrm{f}(5)+\mathrm{f}(397)=0$.

|

0

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

The function $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})$ is defined on the positive integers and takes non-negative integer values. It satisfies (1) $f(m n)=f(m)+f(n),(2) f(n)=0$ if the last digit of $n$ is 3 , (3) $f(10)=0$. Find $\mathrm{f}(1985)$.

|

If $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{mn})=0$, then $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{m})+\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})=0($ by $(1))$. But $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{m})$ and $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})$ are non-negative, so $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{m})=\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})=$ 0 . Thus $f(10)=0$ implies $f(5)=0$. Similarly $f(3573)=0$ by (2), so $f(397)=0$. Hence $f(1985)$ $=\mathrm{f}(5)+\mathrm{f}(397)=0$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IberoAmerican_MO/segmented/en-1985-2003-IberoamericanMO.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n## Problem B2",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution"

}

|

f43a5baa-76cf-512b-8898-06634088185f

| 604,757

|

Find a number $\mathrm{N}$ with five digits, all different and none zero, which equals the sum of all distinct three digit numbers whose digits are all different and are all digits of $\mathrm{N}$.

|

Answer: 35964

There are $4.3=12$ numbers with a given digit of $n$ in the units place. Similarly, there are 12 with it in the tens place and 12 with it in the hundreds place. So the sum of the 3 digit numbers is $12.111(\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c}+\mathrm{d}+\mathrm{e})$, where $\mathrm{n}=\mathrm{abcde}$. So $8668 \mathrm{a}=332 \mathrm{~b}+1232 \mathrm{c}+1322 \mathrm{~d}+$ 1331e. We can easily see that $\mathrm{a}=1$ is too small and $\mathrm{a}=4$ is too big, so $\mathrm{a}=2$ or 3 . Obviously e must be even. 0 is too small, so $\mathrm{e}=2,4,6$ or 8 . Working mod 11 , we see that $0=2 \mathrm{~b}+2 \mathrm{~d}$, so $\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{d}=11$. Working $\bmod 7$, we see that $2 \mathrm{a}=3 \mathrm{~b}+6 \mathrm{~d}+\mathrm{e}$. Using the $\bmod 11$ result, $\mathrm{b}=2, \mathrm{~d}=$ 9 or $b=3, d=8$ or $b=4, d=7$ or $b=5, d=6$ or $b=6, d=5$ or $b=7, d=4$ or $b=8, d=3$ or $\mathrm{b}=9, \mathrm{~d}=2$. Putting each of these into the $\bmod 7$ result gives $2 \mathrm{a}-\mathrm{e}=4,1,5,2,6,3,0,4$ mod 7. So putting $\mathrm{a}=2$ and remembering that $\mathrm{e}$ must be $2,4,6,8$ and that all digits must be different gives a, b, d, e = 2,4, 7, 6 or 2, 7, 4, 8 or 2, 8, 3, 4 as the only possibilities. It is then straightforward but tiresome to check that none of these give a solution for $\mathrm{c}$. Similarly putting $\mathrm{a}=4$, gives $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{d}, \mathrm{e}=3,4,7,8$ or $3,5,6,4$ as the only possibilities. Checking, we find the solution above and no others.

|

35964

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find a number $\mathrm{N}$ with five digits, all different and none zero, which equals the sum of all distinct three digit numbers whose digits are all different and are all digits of $\mathrm{N}$.

|

Answer: 35964

There are $4.3=12$ numbers with a given digit of $n$ in the units place. Similarly, there are 12 with it in the tens place and 12 with it in the hundreds place. So the sum of the 3 digit numbers is $12.111(\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c}+\mathrm{d}+\mathrm{e})$, where $\mathrm{n}=\mathrm{abcde}$. So $8668 \mathrm{a}=332 \mathrm{~b}+1232 \mathrm{c}+1322 \mathrm{~d}+$ 1331e. We can easily see that $\mathrm{a}=1$ is too small and $\mathrm{a}=4$ is too big, so $\mathrm{a}=2$ or 3 . Obviously e must be even. 0 is too small, so $\mathrm{e}=2,4,6$ or 8 . Working mod 11 , we see that $0=2 \mathrm{~b}+2 \mathrm{~d}$, so $\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{d}=11$. Working $\bmod 7$, we see that $2 \mathrm{a}=3 \mathrm{~b}+6 \mathrm{~d}+\mathrm{e}$. Using the $\bmod 11$ result, $\mathrm{b}=2, \mathrm{~d}=$ 9 or $b=3, d=8$ or $b=4, d=7$ or $b=5, d=6$ or $b=6, d=5$ or $b=7, d=4$ or $b=8, d=3$ or $\mathrm{b}=9, \mathrm{~d}=2$. Putting each of these into the $\bmod 7$ result gives $2 \mathrm{a}-\mathrm{e}=4,1,5,2,6,3,0,4$ mod 7. So putting $\mathrm{a}=2$ and remembering that $\mathrm{e}$ must be $2,4,6,8$ and that all digits must be different gives a, b, d, e = 2,4, 7, 6 or 2, 7, 4, 8 or 2, 8, 3, 4 as the only possibilities. It is then straightforward but tiresome to check that none of these give a solution for $\mathrm{c}$. Similarly putting $\mathrm{a}=4$, gives $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{d}, \mathrm{e}=3,4,7,8$ or $3,5,6,4$ as the only possibilities. Checking, we find the solution above and no others.

|

{

"resource_path": "IberoAmerican_MO/segmented/en-1985-2003-IberoamericanMO.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n## Problem B1",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution"

}

|

af2e0667-9918-5e98-a691-1eb266db83ff

| 604,425

|

$a_{n}$ is the last digit of $1+2+\ldots+n$. Find $a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{1992}$.

|

It is easy to compile the following table, from which we see that $\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{n}}$ is periodic with period 20 , and indeed the sum for each decade (from 0 to 9 ) is 35 . Thus the sum for 1992 is $199.35+5+$ $6+8=6984$.

| $\mathrm{n}$ | | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| $a_{\mathrm{n}}$ | | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | | | | | | | | | | 6 | | 1 | 5 | | |

| sum | | 0 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 24 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 46 | 54 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 66 |

| 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

6984

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

$a_{n}$ is the last digit of $1+2+\ldots+n$. Find $a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{1992}$.

|

It is easy to compile the following table, from which we see that $\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{n}}$ is periodic with period 20 , and indeed the sum for each decade (from 0 to 9 ) is 35 . Thus the sum for 1992 is $199.35+5+$ $6+8=6984$.

| $\mathrm{n}$ | | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| $a_{\mathrm{n}}$ | | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | | | | | | | | | | 6 | | 1 | 5 | | |

| sum | | 0 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 24 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 46 | 54 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 66 |

| 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

{

"resource_path": "IberoAmerican_MO/segmented/en-1985-2003-IberoamericanMO.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n## Problem A1",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution"

}

|

e0e71d23-0809-5691-91a4-f95fa638095a

| 604,464

|

Let $f(x)=a_{1} /\left(x+a_{1}\right)+a_{2} /\left(x+a_{2}\right)+\ldots+a_{n} /\left(x+a_{n}\right)$, where $a_{i}$ are unequal positive reals. Find the sum of the lengths of the intervals in which $f(x) \geq 1$.

Answer

$\sum a_{i}$

|

wlog $a_{1}>a_{2}>\ldots>a_{n}$. The graph of each $a_{i} /\left(x+a_{i}\right)$ is a rectangular hyberbola with asymptotes $x=-a_{i}$ and $y=0$. So it is not hard to see that the graph of $f(x)$ is made up of $n+1$ strictly decreasing parts. For $\mathrm{x}<-\mathrm{a}_{1}, \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})$ is negative. For $\mathrm{x} \square\left(-\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{i}},-\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{i}+1}\right), \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})$ decreases from $\infty$ to $-\infty$. Finally, for $\mathrm{x}>-\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{n}}, \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})$ decreases from $\infty$ to 0 . Thus $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})=1$ at $\mathrm{n}$ values $\mathrm{b}_{1}<\mathrm{b}_{2}<\ldots<\mathrm{b}_{\mathrm{n}}$, and $f(x) \geq 1$ on the $n$ intervals $\left(-a_{1}, b_{1}\right),\left(-a_{2}, b_{2}\right), \ldots,\left(-a_{n}, b_{n}\right)$. So the sum of the lengths of these intervals is $\sum\left(a_{i}+b_{i}\right)$. We show that $\sum b_{i}=0$.

Multiplying $f(x)=1$ by $\prod\left(x+a_{j}\right)$ we get a polynomial of degree $n$ :

$$

\Pi\left(x+a_{j}\right)-\sum_{i}\left(a_{i} \prod_{j \neq i}\left(x+a_{j}\right)\right)=0

$$

The coefficient of $x^{n}$ is 1 and the coefficient of $x^{n-1}$ is $\sum a_{j}-\sum a_{i}=0$. Hence the sum of the roots, which is $\sum b_{i}$, is zero.

|

\sum a_{i}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $f(x)=a_{1} /\left(x+a_{1}\right)+a_{2} /\left(x+a_{2}\right)+\ldots+a_{n} /\left(x+a_{n}\right)$, where $a_{i}$ are unequal positive reals. Find the sum of the lengths of the intervals in which $f(x) \geq 1$.

Answer

$\sum a_{i}$

|

wlog $a_{1}>a_{2}>\ldots>a_{n}$. The graph of each $a_{i} /\left(x+a_{i}\right)$ is a rectangular hyberbola with asymptotes $x=-a_{i}$ and $y=0$. So it is not hard to see that the graph of $f(x)$ is made up of $n+1$ strictly decreasing parts. For $\mathrm{x}<-\mathrm{a}_{1}, \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})$ is negative. For $\mathrm{x} \square\left(-\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{i}},-\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{i}+1}\right), \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})$ decreases from $\infty$ to $-\infty$. Finally, for $\mathrm{x}>-\mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{n}}, \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})$ decreases from $\infty$ to 0 . Thus $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})=1$ at $\mathrm{n}$ values $\mathrm{b}_{1}<\mathrm{b}_{2}<\ldots<\mathrm{b}_{\mathrm{n}}$, and $f(x) \geq 1$ on the $n$ intervals $\left(-a_{1}, b_{1}\right),\left(-a_{2}, b_{2}\right), \ldots,\left(-a_{n}, b_{n}\right)$. So the sum of the lengths of these intervals is $\sum\left(a_{i}+b_{i}\right)$. We show that $\sum b_{i}=0$.

Multiplying $f(x)=1$ by $\prod\left(x+a_{j}\right)$ we get a polynomial of degree $n$ :

$$

\Pi\left(x+a_{j}\right)-\sum_{i}\left(a_{i} \prod_{j \neq i}\left(x+a_{j}\right)\right)=0

$$

The coefficient of $x^{n}$ is 1 and the coefficient of $x^{n-1}$ is $\sum a_{j}-\sum a_{i}=0$. Hence the sum of the roots, which is $\sum b_{i}$, is zero.

|

{

"resource_path": "IberoAmerican_MO/segmented/en-1985-2003-IberoamericanMO.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n## Problem A2",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution"

}

|

7b623153-948f-527e-9be5-8b2fba21dcc8

| 604,476

|

$\mathrm{ABCD}$ is an $\mathrm{n} \mathrm{x}$ board. We call a diagonal row of cells a positive diagonal if it is parallel to AC. How many coins must be placed on an $\mathrm{n} x \mathrm{n}$ board such that every cell either has a coin or is in the same row, column or positive diagonal as a coin?

## Answer

smallest integer $\geq(2 n-1) / 3$

[so $2 \mathrm{~m}-1$ for $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}-1,2 \mathrm{~m}$ for $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}, 2 \mathrm{~m}+1$ for $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}+1$ ]

|

There must be at least $\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}$ rows without a coin and at least $\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}$ columns without a coin. Let $\mathrm{r}_{1}$, $\mathrm{r}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{r}_{\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}}$ be cells in the top row without a coin which are also in a column without a coin. Let $\mathrm{r}_{1}, \mathrm{c}_{2}, \mathrm{c}_{3}, \ldots, \mathrm{c}_{\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}}$ be cells in the first column without a coin which are also in a row without a coin. Each of the $2 \mathrm{n}-2 \mathrm{k}-1 \mathrm{r}_{\mathrm{i}}$ and $\mathrm{c}_{\mathrm{j}}$ are on a different positive diagonal, so we must have $\mathrm{k} \geq$ $2 n-2 k-1$ and hence $k \geq(2 n-1) / 3$.

Let (i,j) denote the cell in row $\mathrm{i}$, col $\mathrm{j}$. For $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}-1$, put coins in (m,1), $(\mathrm{m}-1,2),(m-2,3), \ldots$, $(1, m)$ and in $(2 m-1, m+1),(2 m-2, m+2), \ldots,(m+1,2 m-1)$. It is easy to check that this works. For $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}$, put an additional coin in ( $2 \mathrm{~m}, 2 \mathrm{~m}$ ), it is easy to check that works. For $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}+1$ we can use the same arrangement as for $3 m+2$.

|

(2 n-1) / 3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

$\mathrm{ABCD}$ is an $\mathrm{n} \mathrm{x}$ board. We call a diagonal row of cells a positive diagonal if it is parallel to AC. How many coins must be placed on an $\mathrm{n} x \mathrm{n}$ board such that every cell either has a coin or is in the same row, column or positive diagonal as a coin?

## Answer

smallest integer $\geq(2 n-1) / 3$

[so $2 \mathrm{~m}-1$ for $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}-1,2 \mathrm{~m}$ for $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}, 2 \mathrm{~m}+1$ for $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}+1$ ]

|

There must be at least $\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}$ rows without a coin and at least $\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}$ columns without a coin. Let $\mathrm{r}_{1}$, $\mathrm{r}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{r}_{\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}}$ be cells in the top row without a coin which are also in a column without a coin. Let $\mathrm{r}_{1}, \mathrm{c}_{2}, \mathrm{c}_{3}, \ldots, \mathrm{c}_{\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{k}}$ be cells in the first column without a coin which are also in a row without a coin. Each of the $2 \mathrm{n}-2 \mathrm{k}-1 \mathrm{r}_{\mathrm{i}}$ and $\mathrm{c}_{\mathrm{j}}$ are on a different positive diagonal, so we must have $\mathrm{k} \geq$ $2 n-2 k-1$ and hence $k \geq(2 n-1) / 3$.

Let (i,j) denote the cell in row $\mathrm{i}$, col $\mathrm{j}$. For $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}-1$, put coins in (m,1), $(\mathrm{m}-1,2),(m-2,3), \ldots$, $(1, m)$ and in $(2 m-1, m+1),(2 m-2, m+2), \ldots,(m+1,2 m-1)$. It is easy to check that this works. For $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}$, put an additional coin in ( $2 \mathrm{~m}, 2 \mathrm{~m}$ ), it is easy to check that works. For $\mathrm{n}=3 \mathrm{~m}+1$ we can use the same arrangement as for $3 m+2$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IberoAmerican_MO/segmented/en-1985-2003-IberoamericanMO.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n## Problem B1",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution"

}

|

5bd22e5b-473b-5ee7-ad38-c7949e05ed2a

| 604,679

|

Find the smallest positive integer $\mathrm{n}$ so that a cube with side $\mathrm{n}$ can be divided into 1996 cubes each with side a positive integer.

|

Answer: 13.

Divide all the cubes into unit cubes. Then the 1996 cubes must each contain at least one unit cube, so the large cube contains at least 1996 unit cubes. But $12^{3}=1728<1996<2197=13^{3}$, so it is certainly not possible for $\mathrm{n}<13$.

It can be achieved with 13 by $1.5^{3}+11.2^{3}+1984.1^{3}=13^{3}$ (actually packing the cubes together to form a $13 \times 13 \times 13$ cube is trivial since there are so many unit cubes).

## Problem 2

$\mathrm{M}$ is the midpoint of the median $\mathrm{AD}$ of the triangle $\mathrm{ABC}$. The ray $\mathrm{BM}$ meets $\mathrm{AC}$ at $N$. Show that $\mathrm{AB}$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $\mathrm{NBC}$ iff $\mathrm{BM} / \mathrm{BN}=(\mathrm{BC} / \mathrm{BN})^{2}$.

|

13

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find the smallest positive integer $\mathrm{n}$ so that a cube with side $\mathrm{n}$ can be divided into 1996 cubes each with side a positive integer.

|

Answer: 13.

Divide all the cubes into unit cubes. Then the 1996 cubes must each contain at least one unit cube, so the large cube contains at least 1996 unit cubes. But $12^{3}=1728<1996<2197=13^{3}$, so it is certainly not possible for $\mathrm{n}<13$.

It can be achieved with 13 by $1.5^{3}+11.2^{3}+1984.1^{3}=13^{3}$ (actually packing the cubes together to form a $13 \times 13 \times 13$ cube is trivial since there are so many unit cubes).

## Problem 2

$\mathrm{M}$ is the midpoint of the median $\mathrm{AD}$ of the triangle $\mathrm{ABC}$. The ray $\mathrm{BM}$ meets $\mathrm{AC}$ at $N$. Show that $\mathrm{AB}$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $\mathrm{NBC}$ iff $\mathrm{BM} / \mathrm{BN}=(\mathrm{BC} / \mathrm{BN})^{2}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "IberoAmerican_MO/segmented/en-1985-2003-IberoamericanMO.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n## Problem A1",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution"

}

|

355a613d-8bb8-5ac8-bfc5-9134703a639a

| 604,704

|