problem

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution

stringlengths 3

10k

| answer

stringlengths 1

91

| problem_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | question_type

stringclasses 1

value | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 3

10k

| metadata

dict | uuid

stringlengths 36

36

| id

int64 22.6k

612k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The mathematician John is having trouble remembering his girlfriend Alicia's 7-digit phone number. He remembers that the first four digits consist of one 1 , one 2 , and two 3 s . He also remembers that the fifth digit is either a 4 or 5 . While he has no memory of the sixth digit, he remembers that the seventh digit is 9 minus the sixth digit. If this is all the information he has, how many phone numbers does he have to try if he is to make sure he dials the correct number?

|

There are $\frac{4!}{2!}=12$ possibilities for the first four digits. There are two possibilities for the fifth digit. There are 10 possibilities for the sixth digit, and this uniquely determines the seventh digit. So he has to dial $12 \cdot 2 \cdot 10=240$ numbers.

|

240

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

The mathematician John is having trouble remembering his girlfriend Alicia's 7-digit phone number. He remembers that the first four digits consist of one 1 , one 2 , and two 3 s . He also remembers that the fifth digit is either a 4 or 5 . While he has no memory of the sixth digit, he remembers that the seventh digit is 9 minus the sixth digit. If this is all the information he has, how many phone numbers does he have to try if he is to make sure he dials the correct number?

|

There are $\frac{4!}{2!}=12$ possibilities for the first four digits. There are two possibilities for the fifth digit. There are 10 possibilities for the sixth digit, and this uniquely determines the seventh digit. So he has to dial $12 \cdot 2 \cdot 10=240$ numbers.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n10. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

ae62fa82-5370-570b-a1a9-3251ace071fe

| 611,018

|

How many real solutions are there to the equation

$$

||||x|-2|-2|-2|=||||x|-3|-3|-3| ?

$$

|

6. The graphs of the two sides of the equation can be graphed on the same plot to reveal six intersection points.

|

6

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

How many real solutions are there to the equation

$$

||||x|-2|-2|-2|=||||x|-3|-3|-3| ?

$$

|

6. The graphs of the two sides of the equation can be graphed on the same plot to reveal six intersection points.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n11. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

6d8f1093-7400-5bce-9325-e21ef28a0d3f

| 611,019

|

An omino is a 1-by-1 square or a 1-by-2 horizontal rectangle. An omino tiling of a region of the plane is a way of covering it (and only it) by ominoes. How many omino tilings are there of a 2 -by- 10 horizontal rectangle?

|

There are exactly as many omino tilings of a 1 -by- $n$ rectangle as there are domino tilings of a 2 -by- $n$ rectangle. Since the rows don't interact at all, the number of omino tilings of an $m$-by- $n$ rectangle is the number of omino tilings of a 1-by- $n$ rectangle raised to the $m$ th power, $F_{n}^{m}$. The answer is $89^{2}=7921$.

|

7921

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

An omino is a 1-by-1 square or a 1-by-2 horizontal rectangle. An omino tiling of a region of the plane is a way of covering it (and only it) by ominoes. How many omino tilings are there of a 2 -by- 10 horizontal rectangle?

|

There are exactly as many omino tilings of a 1 -by- $n$ rectangle as there are domino tilings of a 2 -by- $n$ rectangle. Since the rows don't interact at all, the number of omino tilings of an $m$-by- $n$ rectangle is the number of omino tilings of a 1-by- $n$ rectangle raised to the $m$ th power, $F_{n}^{m}$. The answer is $89^{2}=7921$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n14. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

c611047e-f623-55c9-9765-59b381221f29

| 611,022

|

How many sequences of 0 s and 1 s are there of length 10 such that there are no three 0 s or 1 s consecutively anywhere in the sequence?

|

We can have blocks of either 1 or 20 s and 1 s , and these blocks must be alternating between 0 s and 1 s . The number of ways of arranging blocks to form a sequence of length $n$ is the same as the number of omino tilings of a $1-b y-n$ rectangle, and we may start each sequence with a 0 or a 1 , making $2 F_{n}$ or, in this case, 178 sequences.

|

178

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

How many sequences of 0 s and 1 s are there of length 10 such that there are no three 0 s or 1 s consecutively anywhere in the sequence?

|

We can have blocks of either 1 or 20 s and 1 s , and these blocks must be alternating between 0 s and 1 s . The number of ways of arranging blocks to form a sequence of length $n$ is the same as the number of omino tilings of a $1-b y-n$ rectangle, and we may start each sequence with a 0 or a 1 , making $2 F_{n}$ or, in this case, 178 sequences.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n15. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

f65b2fb3-3daa-5017-b560-27ca227305bc

| 611,023

|

Divide an $m$-by- $n$ rectangle into $m n$ nonoverlapping 1-by-1 squares. A polyomino of this rectangle is a subset of these unit squares such that for any two unit squares $S, T$ in the polyomino, either

(1) $S$ and $T$ share an edge or

(2) there exists a positive integer $n$ such that the polyomino contains unit squares $S_{1}, S_{2}, S_{3}, \ldots, S_{n}$ such that $S$ and $S_{1}$ share an edge, $S_{n}$ and $T$ share an edge, and for all positive integers $k<n, S_{k}$ and $S_{k+1}$ share an edge.

We say a polyomino of a given rectangle spans the rectangle if for each of the four edges of the rectangle the polyomino contains a square whose edge lies on it.

What is the minimum number of unit squares a polyomino can have if it spans a 128 -by343 rectangle?

|

To span an $a \times b$ rectangle, we need at least $a+b-1$ squares. Indeed, consider a square of the polyomino bordering the left edge of the rectangle and one bordering the right edge. There exists a path connecting these squares; suppose it runs through $c$ different rows. Then the path requires at least $b-1$ horizontal and $c-1$ vertical steps, so it uses at least $b+c-1$ different squares. However, since the polyomino also hits the top and bottom edges of the rectangle, it must run into the remaining $a-c$ rows as well, so altogether we need at least $a+b-1$ squares. On the other hand, this many squares suffice - just consider all the squares bordering the lower or right edges of the rectangle. So, in our case, the answer is $128+343-1=470$.

|

470

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Divide an $m$-by- $n$ rectangle into $m n$ nonoverlapping 1-by-1 squares. A polyomino of this rectangle is a subset of these unit squares such that for any two unit squares $S, T$ in the polyomino, either

(1) $S$ and $T$ share an edge or

(2) there exists a positive integer $n$ such that the polyomino contains unit squares $S_{1}, S_{2}, S_{3}, \ldots, S_{n}$ such that $S$ and $S_{1}$ share an edge, $S_{n}$ and $T$ share an edge, and for all positive integers $k<n, S_{k}$ and $S_{k+1}$ share an edge.

We say a polyomino of a given rectangle spans the rectangle if for each of the four edges of the rectangle the polyomino contains a square whose edge lies on it.

What is the minimum number of unit squares a polyomino can have if it spans a 128 -by343 rectangle?

|

To span an $a \times b$ rectangle, we need at least $a+b-1$ squares. Indeed, consider a square of the polyomino bordering the left edge of the rectangle and one bordering the right edge. There exists a path connecting these squares; suppose it runs through $c$ different rows. Then the path requires at least $b-1$ horizontal and $c-1$ vertical steps, so it uses at least $b+c-1$ different squares. However, since the polyomino also hits the top and bottom edges of the rectangle, it must run into the remaining $a-c$ rows as well, so altogether we need at least $a+b-1$ squares. On the other hand, this many squares suffice - just consider all the squares bordering the lower or right edges of the rectangle. So, in our case, the answer is $128+343-1=470$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n16. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

8155aaf4-17c5-5e04-9cb8-5fd0408fceac

| 611,024

|

Find the number of pentominoes (5-square polyominoes) that span a 3 -by- 3 rectangle, where polyominoes that are flips or rotations of each other are considered the same polyomino.

|

By enumeration, the answer is 6 .

|

6

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Find the number of pentominoes (5-square polyominoes) that span a 3 -by- 3 rectangle, where polyominoes that are flips or rotations of each other are considered the same polyomino.

|

By enumeration, the answer is 6 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n17. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

c8eaca65-a94e-5079-a02f-c2921cbd66f7

| 611,025

|

For how many integers $a(1 \leq a \leq 200)$ is the number $a^{a}$ a square?

|

107 If $a$ is even, we have $a^{a}=\left(a^{a / 2}\right)^{2}$. If $a$ is odd, $a^{a}=\left(a^{(a-1) / 2}\right)^{2} \cdot a$, which is a square precisely when $a$ is. Thus we have 100 even values of $a$ and 7 odd square values $\left(1^{2}, 3^{2}, \ldots, 13^{2}\right)$ for a total of 107 .

|

107

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

For how many integers $a(1 \leq a \leq 200)$ is the number $a^{a}$ a square?

|

107 If $a$ is even, we have $a^{a}=\left(a^{a / 2}\right)^{2}$. If $a$ is odd, $a^{a}=\left(a^{(a-1) / 2}\right)^{2} \cdot a$, which is a square precisely when $a$ is. Thus we have 100 even values of $a$ and 7 odd square values $\left(1^{2}, 3^{2}, \ldots, 13^{2}\right)$ for a total of 107 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n19. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

83648f60-58c6-50bd-9b58-cb144999acba

| 611,027

|

The Antarctican language has an alphabet of just 16 letters. Interestingly, every word in the language has exactly 3 letters, and it is known that no word's first letter equals any word's last letter (for instance, if the alphabet were $\{a, b\}$ then $a a b$ and aaa could not both be words in the language because $a$ is the first letter of a word and the last letter of a word; in fact, just aaa alone couldn't be in the language). Given this, determine the maximum possible number of words in the language.

|

1024 Every letter can be the first letter of a word, or the last letter of a word, or possibly neither, but not both. If there are $a$ different first letters and $b$ different last letters, then we can form $a \cdot 16 \cdot b$ different words (and the desired conditions will be met). Given the constraints $0 \leq a, b ; a+b \leq 16$, this product is maximized when $a=b=8$, giving the answer.

|

1024

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

The Antarctican language has an alphabet of just 16 letters. Interestingly, every word in the language has exactly 3 letters, and it is known that no word's first letter equals any word's last letter (for instance, if the alphabet were $\{a, b\}$ then $a a b$ and aaa could not both be words in the language because $a$ is the first letter of a word and the last letter of a word; in fact, just aaa alone couldn't be in the language). Given this, determine the maximum possible number of words in the language.

|

1024 Every letter can be the first letter of a word, or the last letter of a word, or possibly neither, but not both. If there are $a$ different first letters and $b$ different last letters, then we can form $a \cdot 16 \cdot b$ different words (and the desired conditions will be met). Given the constraints $0 \leq a, b ; a+b \leq 16$, this product is maximized when $a=b=8$, giving the answer.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n20. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

d46272a9-7e26-56ce-b598-6a3e5249afee

| 611,028

|

The Dyslexian alphabet consists of consonants and vowels. It so happens that a finite sequence of letters is a word in Dyslexian precisely if it alternates between consonants and vowels (it may begin with either). There are 4800 five-letter words in Dyslexian. How many letters are in the alphabet?

|

12 Suppose there are consonants, $v$ vowels. Then there are $c \cdot v \cdot c \cdot v \cdot c+$ $v \cdot c \cdot v \cdot c \cdot v=(c v)^{2}(c+v)$ five-letter words. Thus, $c+v=4800 /(c v)^{2}=3 \cdot(40 / c v)^{2}$, so $c v$ is a divisor of 40 . If $c v \leq 10$, we have $c+v \geq 48$, impossible for $c, v$ integers; if $c v=40$, then $c+v=3$ which is again impossible. So $c v=20$, giving $c+v=12$, the answer. As a check, this does have integer solutions: $(c, v)=(2,10)$ or $(10,2)$.

|

12

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

The Dyslexian alphabet consists of consonants and vowels. It so happens that a finite sequence of letters is a word in Dyslexian precisely if it alternates between consonants and vowels (it may begin with either). There are 4800 five-letter words in Dyslexian. How many letters are in the alphabet?

|

12 Suppose there are consonants, $v$ vowels. Then there are $c \cdot v \cdot c \cdot v \cdot c+$ $v \cdot c \cdot v \cdot c \cdot v=(c v)^{2}(c+v)$ five-letter words. Thus, $c+v=4800 /(c v)^{2}=3 \cdot(40 / c v)^{2}$, so $c v$ is a divisor of 40 . If $c v \leq 10$, we have $c+v \geq 48$, impossible for $c, v$ integers; if $c v=40$, then $c+v=3$ which is again impossible. So $c v=20$, giving $c+v=12$, the answer. As a check, this does have integer solutions: $(c, v)=(2,10)$ or $(10,2)$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n21. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

0dc73851-0a6b-5930-8274-b39278fd8b1c

| 611,029

|

Find $P(7,3)$.

|

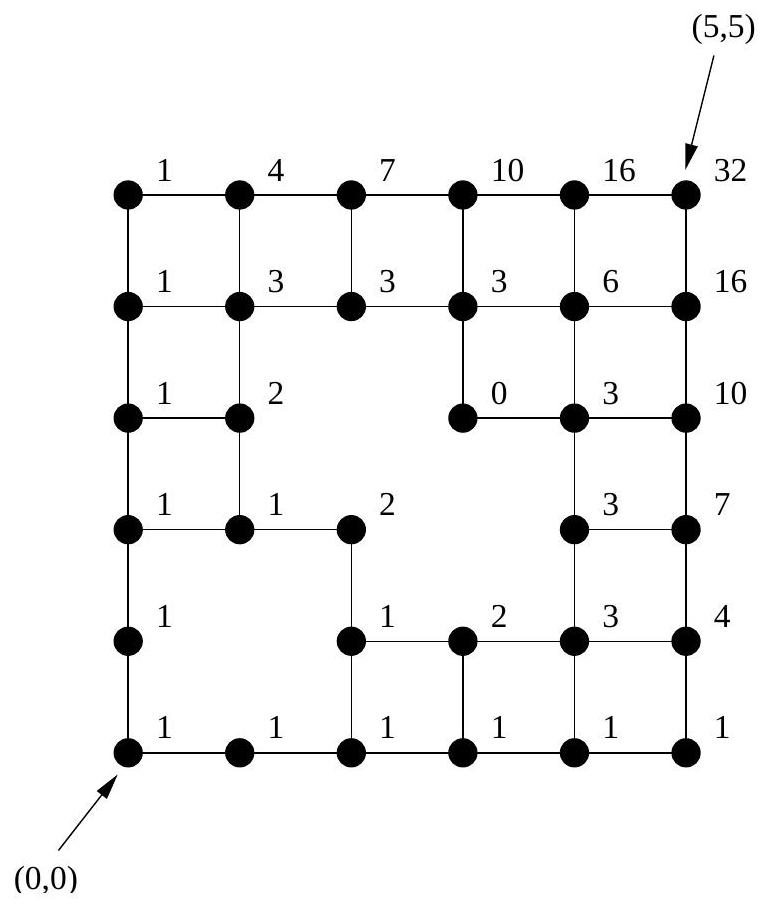

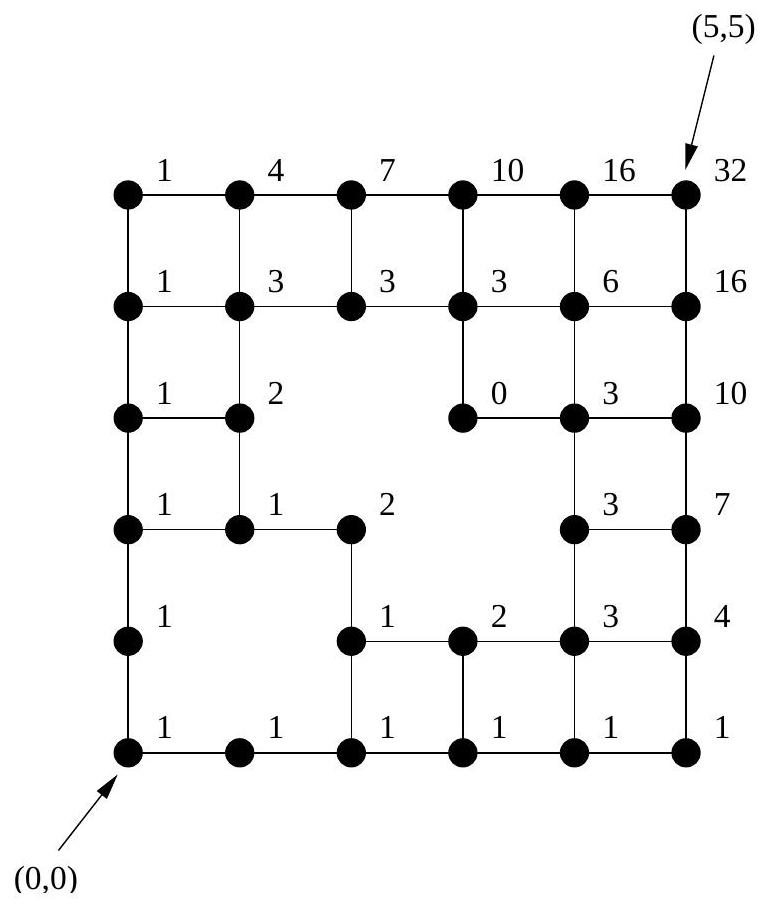

The number of paths that start at $(0,0)$ and end at $(n, m)$ is $\binom{n+m}{n}$, since we must choose $n$ of our $n+m$ steps to be rightward steps. In this case, the answer is 120 .

|

120

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Find $P(7,3)$.

|

The number of paths that start at $(0,0)$ and end at $(n, m)$ is $\binom{n+m}{n}$, since we must choose $n$ of our $n+m$ steps to be rightward steps. In this case, the answer is 120 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n23. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

6e587f89-b94f-514d-9b60-c25381648c59

| 611,031

|

A restricted path of length $n$ is a path of length $n$ such that for all $i$ between 1 and $n-2$ inclusive, if the $i$ th step is upward, the $i+1$ st step must be rightward.

Find the number of restricted paths that start at $(0,0)$ and end at $(7,3)$.

|

This is equal to the number of lattice paths from $(0,0)$ to $(7,3)$ that use only rightward and diagonal (upward+rightward) steps plus the number of lattice paths from $(0,0)$ to $(7,2)$ that use only rightward and diagonal steps, which is equal to the number of paths (as defined above) from $(0,0)$ to $(4,3)$ plus the number of paths from $(0,0)$ to $(5,2)$, or $\binom{4+3}{3}+\binom{5+2}{2}=56$.

|

56

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

A restricted path of length $n$ is a path of length $n$ such that for all $i$ between 1 and $n-2$ inclusive, if the $i$ th step is upward, the $i+1$ st step must be rightward.

Find the number of restricted paths that start at $(0,0)$ and end at $(7,3)$.

|

This is equal to the number of lattice paths from $(0,0)$ to $(7,3)$ that use only rightward and diagonal (upward+rightward) steps plus the number of lattice paths from $(0,0)$ to $(7,2)$ that use only rightward and diagonal steps, which is equal to the number of paths (as defined above) from $(0,0)$ to $(4,3)$ plus the number of paths from $(0,0)$ to $(5,2)$, or $\binom{4+3}{3}+\binom{5+2}{2}=56$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n24. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

1a878f8b-b76a-50c5-a645-5b0ed0cb483e

| 611,032

|

A math professor stands up in front of a room containing 100 very smart math students and says, "Each of you has to write down an integer between 0 and 100, inclusive, to guess 'two-thirds of the average of all the responses.' Each student who guesses the highest integer that is not higher than two-thirds of the average of all responses will receive a prize." If among all the students it is common knowledge that everyone will write down the best response, and there is no communication between students, what single integer should each of the 100 students write down?

|

Since the average cannot be greater than 100, no student will write down a number greater than $\frac{2}{3} \cdot 100$. But then the average cannot be greater than $\frac{2}{3} \cdot 100$, and, realizing this, each student will write down a number no greater than $\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2} \cdot 100$. Continuing in this manner, we eventually see that no student will write down an integer greater than 0 , so this is the answer.

|

0

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

A math professor stands up in front of a room containing 100 very smart math students and says, "Each of you has to write down an integer between 0 and 100, inclusive, to guess 'two-thirds of the average of all the responses.' Each student who guesses the highest integer that is not higher than two-thirds of the average of all responses will receive a prize." If among all the students it is common knowledge that everyone will write down the best response, and there is no communication between students, what single integer should each of the 100 students write down?

|

Since the average cannot be greater than 100, no student will write down a number greater than $\frac{2}{3} \cdot 100$. But then the average cannot be greater than $\frac{2}{3} \cdot 100$, and, realizing this, each student will write down a number no greater than $\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2} \cdot 100$. Continuing in this manner, we eventually see that no student will write down an integer greater than 0 , so this is the answer.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n25. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

b6033d0b-6b7d-571f-8e5e-df0f9be47fc6

| 611,033

|

Consider the two hands of an analog clock, each of which moves with constant angular velocity. Certain positions of these hands are possible (e.g. the hour hand halfway between the 5 and 6 and the minute hand exactly at the 6 ), while others are impossible (e.g. the hour hand exactly at the 5 and the minute hand exactly at the 6 ). How many different positions are there that would remain possible if the hour and minute hands were switched?

|

143 We can look at the twelve-hour cycle beginning at midnight and ending just before noon, since during this time, the clock goes through each possible position exactly once. The minute hand has twelve times the angular velocity of the hour hand, so if the hour hand has made $t$ revolutions from its initial position $(0 \leq t<1)$, the minute hand has made $12 t$ revolutions. If the hour hand were to have made $12 t$ revolutions, the minute hand would have made $144 t$. So we get a valid configuration by reversing the hands precisely when $144 t$ revolutions land the hour hand in the same place as $t$ revolutions - i.e. when $143 t=144 t-t$ is an integer, which clearly occurs for exactly 143 values of $t$ corresponding to distinct positions on the clock ( $144-1=143$ ).

|

143

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

Consider the two hands of an analog clock, each of which moves with constant angular velocity. Certain positions of these hands are possible (e.g. the hour hand halfway between the 5 and 6 and the minute hand exactly at the 6 ), while others are impossible (e.g. the hour hand exactly at the 5 and the minute hand exactly at the 6 ). How many different positions are there that would remain possible if the hour and minute hands were switched?

|

143 We can look at the twelve-hour cycle beginning at midnight and ending just before noon, since during this time, the clock goes through each possible position exactly once. The minute hand has twelve times the angular velocity of the hour hand, so if the hour hand has made $t$ revolutions from its initial position $(0 \leq t<1)$, the minute hand has made $12 t$ revolutions. If the hour hand were to have made $12 t$ revolutions, the minute hand would have made $144 t$. So we get a valid configuration by reversing the hands precisely when $144 t$ revolutions land the hour hand in the same place as $t$ revolutions - i.e. when $143 t=144 t-t$ is an integer, which clearly occurs for exactly 143 values of $t$ corresponding to distinct positions on the clock ( $144-1=143$ ).

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n27. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

a536c1d5-4bd2-5f6f-9743-0bcd0202231b

| 611,035

|

Count how many 8-digit numbers there are that contain exactly four nines as digits.

|

There are $\binom{8}{4} \cdot 9^{4}$ sequences of 8 numbers with exactly four nines. A sequence of digits of length 8 is not an 8 -digit number, however, if and only if the first digit is zero. There are $\binom{7}{4} 9^{3}$-digit sequences that are not 8 -digit numbers. The answer is thus $\binom{8}{4} \cdot 9^{4}-\binom{7}{4} 9^{3}=433755$.

|

433755

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Count how many 8-digit numbers there are that contain exactly four nines as digits.

|

There are $\binom{8}{4} \cdot 9^{4}$ sequences of 8 numbers with exactly four nines. A sequence of digits of length 8 is not an 8 -digit number, however, if and only if the first digit is zero. There are $\binom{7}{4} 9^{3}$-digit sequences that are not 8 -digit numbers. The answer is thus $\binom{8}{4} \cdot 9^{4}-\binom{7}{4} 9^{3}=433755$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n28. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

e919de52-70cf-567f-a2aa-17257d9c6b5c

| 611,036

|

A sequence $s_{0}, s_{1}, s_{2}, s_{3}, \ldots$ is defined by $s_{0}=s_{1}=1$ and, for every positive integer $n, s_{2 n}=s_{n}, s_{4 n+1}=s_{2 n+1}, s_{4 n-1}=s_{2 n-1}+s_{2 n-1}^{2} / s_{n-1}$. What is the value of $s_{1000}$ ?

|

720 Some experimentation with small values may suggest that $s_{n}=k$ !, where $k$ is the number of ones in the binary representation of $n$, and this formula is in fact provable by a straightforward induction. Since $1000_{10}=1111101000_{2}$, with six ones, $s_{1000}=6!=720$.

|

720

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

A sequence $s_{0}, s_{1}, s_{2}, s_{3}, \ldots$ is defined by $s_{0}=s_{1}=1$ and, for every positive integer $n, s_{2 n}=s_{n}, s_{4 n+1}=s_{2 n+1}, s_{4 n-1}=s_{2 n-1}+s_{2 n-1}^{2} / s_{n-1}$. What is the value of $s_{1000}$ ?

|

720 Some experimentation with small values may suggest that $s_{n}=k$ !, where $k$ is the number of ones in the binary representation of $n$, and this formula is in fact provable by a straightforward induction. Since $1000_{10}=1111101000_{2}$, with six ones, $s_{1000}=6!=720$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n29. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

5b7c495d-eeee-506a-887a-155ebbdc263d

| 611,037

|

A conical flask contains some water. When the flask is oriented so that its base is horizontal and lies at the bottom (so that the vertex is at the top), the water is 1 inch deep. When the flask is turned upside-down, so that the vertex is at the bottom, the water is 2 inches deep. What is the height of the cone?

|

$\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{93}}{6}$. Let $h$ be the height, and let $V$ be such that $V h^{3}$ equals the volume of the flask. When the base is at the bottom, the portion of the flask not occupied by water forms a cone similar to the entire flask, with a height of $h-1$; thus its volume is $V(h-1)^{3}$. When the base is at the top, the water occupies a cone with a height of 2 , so its volume is $V \cdot 2^{3}$. Since the water's volume does not change,

$$

\begin{gathered}

V h^{3}-V(h-1)^{3}=8 V \\

\Rightarrow 3 h^{2}-3 h+1=h^{3}-(h-1)^{3}=8 \\

\Rightarrow 3 h^{2}-3 h-7=0 .

\end{gathered}

$$

Solving via the quadratic formula and taking the positive root gives $h=\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{93}}{6}$.

|

\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{93}}{6}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A conical flask contains some water. When the flask is oriented so that its base is horizontal and lies at the bottom (so that the vertex is at the top), the water is 1 inch deep. When the flask is turned upside-down, so that the vertex is at the bottom, the water is 2 inches deep. What is the height of the cone?

|

$\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{93}}{6}$. Let $h$ be the height, and let $V$ be such that $V h^{3}$ equals the volume of the flask. When the base is at the bottom, the portion of the flask not occupied by water forms a cone similar to the entire flask, with a height of $h-1$; thus its volume is $V(h-1)^{3}$. When the base is at the top, the water occupies a cone with a height of 2 , so its volume is $V \cdot 2^{3}$. Since the water's volume does not change,

$$

\begin{gathered}

V h^{3}-V(h-1)^{3}=8 V \\

\Rightarrow 3 h^{2}-3 h+1=h^{3}-(h-1)^{3}=8 \\

\Rightarrow 3 h^{2}-3 h-7=0 .

\end{gathered}

$$

Solving via the quadratic formula and taking the positive root gives $h=\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{93}}{6}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n30. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

25cfcb7f-1f0e-5753-a0df-2a6e3bfa15b9

| 611,038

|

Express, as concisely as possible, the value of the product

$$

\left(0^{3}-350\right)\left(1^{3}-349\right)\left(2^{3}-348\right)\left(3^{3}-347\right) \cdots\left(349^{3}-1\right)\left(350^{3}-0\right)

$$

|

0 . One of the factors is $7^{3}-343=0$, so the whole product is zero.

|

0

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Express, as concisely as possible, the value of the product

$$

\left(0^{3}-350\right)\left(1^{3}-349\right)\left(2^{3}-348\right)\left(3^{3}-347\right) \cdots\left(349^{3}-1\right)\left(350^{3}-0\right)

$$

|

0 . One of the factors is $7^{3}-343=0$, so the whole product is zero.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n31. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

36288ba9-acbd-56a9-8237-d82a7b1c1f94

| 611,039

|

Two circles have radii 13 and 30 , and their centers are 41 units apart. The line through the centers of the two circles intersects the smaller circle at two points; let $A$ be the one outside the larger circle. Suppose $B$ is a point on the smaller circle and $C$ a point on the larger circle such that $B$ is the midpoint of $A C$. Compute the distance $A C$.

|

$12 \sqrt{13}$ Call the large circle's center $O_{1}$. Scale the small circle by a factor of 2 about $A$; we obtain a new circle whose center $O_{2}$ is at a distance of $41-13=28$ from $O_{1}$, and whose radius is 26 . Also, the dilation sends $B$ to $C$, which thus lies on circles $O_{1}$ and $O_{2}$. So points $O_{1}, O_{2}, C$ form a 26-28-30 triangle. Let $H$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$ to $O_{1} O_{2}$; we have $C H=24$ and $H O_{2}=10$. Thus, $H A=36$, and $A C=\sqrt{24^{2}+36^{2}}=12 \sqrt{13}$.

|

12 \sqrt{13}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Two circles have radii 13 and 30 , and their centers are 41 units apart. The line through the centers of the two circles intersects the smaller circle at two points; let $A$ be the one outside the larger circle. Suppose $B$ is a point on the smaller circle and $C$ a point on the larger circle such that $B$ is the midpoint of $A C$. Compute the distance $A C$.

|

$12 \sqrt{13}$ Call the large circle's center $O_{1}$. Scale the small circle by a factor of 2 about $A$; we obtain a new circle whose center $O_{2}$ is at a distance of $41-13=28$ from $O_{1}$, and whose radius is 26 . Also, the dilation sends $B$ to $C$, which thus lies on circles $O_{1}$ and $O_{2}$. So points $O_{1}, O_{2}, C$ form a 26-28-30 triangle. Let $H$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$ to $O_{1} O_{2}$; we have $C H=24$ and $H O_{2}=10$. Thus, $H A=36$, and $A C=\sqrt{24^{2}+36^{2}}=12 \sqrt{13}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n32. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

a561dbda-a3b1-54ba-babc-d8b69911cedf

| 611,040

|

The expression $\lfloor x\rfloor$ denotes the greatest integer less than or equal to $x$. Find the value of

$$

\left\lfloor\frac{2002!}{2001!+2000!+1999!+\cdots+1!}\right\rfloor .

$$

|

2000 We break up 2002! $=2002(2001)$ ! as

$$

\begin{gathered}

2000(2001!)+2 \cdot 2001(2000!)=2000(2001!)+2000(2000!)+2002 \cdot 2000(1999!) \\

>2000(2001!+2000!+1999!+\cdots+1!)

\end{gathered}

$$

On the other hand,

$$

2001(2001!+2000!+\cdots+1!)>2001(2001!+2000!)=2001(2001!)+2001!=2002!

$$

Thus we have $2000<2002!/(2001!+\cdots+1!)<2001$, so the answer is 2000 .

|

2000

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

The expression $\lfloor x\rfloor$ denotes the greatest integer less than or equal to $x$. Find the value of

$$

\left\lfloor\frac{2002!}{2001!+2000!+1999!+\cdots+1!}\right\rfloor .

$$

|

2000 We break up 2002! $=2002(2001)$ ! as

$$

\begin{gathered}

2000(2001!)+2 \cdot 2001(2000!)=2000(2001!)+2000(2000!)+2002 \cdot 2000(1999!) \\

>2000(2001!+2000!+1999!+\cdots+1!)

\end{gathered}

$$

On the other hand,

$$

2001(2001!+2000!+\cdots+1!)>2001(2001!+2000!)=2001(2001!)+2001!=2002!

$$

Thus we have $2000<2002!/(2001!+\cdots+1!)<2001$, so the answer is 2000 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n33. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

2c43d815-d1c3-5861-9edf-72d3663c766c

| 611,041

|

Suppose $a, b, c, d$ are real numbers such that

$$

|a-b|+|c-d|=99 ; \quad|a-c|+|b-d|=1

$$

Determine all possible values of $|a-d|+|b-c|$.

|

99 If $w \geq x \geq y \geq z$ are four arbitrary real numbers, then $|w-z|+|x-y|=$ $|w-y|+|x-z|=w+x-y-z \geq w-x+y-z=|w-x|+|y-z|$. Thus, in our case, two of the three numbers $|a-b|+|c-d|,|a-c|+|b-d|,|a-d|+|b-c|$ are equal, and the third one is less than or equal to these two. Since we have a 99 and a 1 , the third number must be 99 .

|

99

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Suppose $a, b, c, d$ are real numbers such that

$$

|a-b|+|c-d|=99 ; \quad|a-c|+|b-d|=1

$$

Determine all possible values of $|a-d|+|b-c|$.

|

99 If $w \geq x \geq y \geq z$ are four arbitrary real numbers, then $|w-z|+|x-y|=$ $|w-y|+|x-z|=w+x-y-z \geq w-x+y-z=|w-x|+|y-z|$. Thus, in our case, two of the three numbers $|a-b|+|c-d|,|a-c|+|b-d|,|a-d|+|b-c|$ are equal, and the third one is less than or equal to these two. Since we have a 99 and a 1 , the third number must be 99 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n35. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

1cfc4fae-d511-5a67-ad2f-d018d71f193c

| 611,043

|

Call a positive integer "mild" if its base-3 representation never contains the digit 2 . How many values of $n(1 \leq n \leq 1000)$ have the property that $n$ and $n^{2}$ are both mild?

|

7 Such a number, which must consist entirely of 0 's and 1 's in base 3, can never have more than one 1. Indeed, if $n=3^{a}+3^{b}+$ higher powers where $b>a$, then $n^{2}=3^{2 a}+2 \cdot 3^{a+b}+$ higher powers which will not be mild. On the other hand, if $n$ does just have one 1 in base 3, then clearly $n$ and $n^{2}$ are mild. So the values of $n \leq 1000$ that work are $3^{0}, 3^{1}, \ldots, 3^{6}$; there are 7 of them.

|

7

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Call a positive integer "mild" if its base-3 representation never contains the digit 2 . How many values of $n(1 \leq n \leq 1000)$ have the property that $n$ and $n^{2}$ are both mild?

|

7 Such a number, which must consist entirely of 0 's and 1 's in base 3, can never have more than one 1. Indeed, if $n=3^{a}+3^{b}+$ higher powers where $b>a$, then $n^{2}=3^{2 a}+2 \cdot 3^{a+b}+$ higher powers which will not be mild. On the other hand, if $n$ does just have one 1 in base 3, then clearly $n$ and $n^{2}$ are mild. So the values of $n \leq 1000$ that work are $3^{0}, 3^{1}, \ldots, 3^{6}$; there are 7 of them.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n37. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

d82e470e-e509-5f67-8da4-19a05ffc0c91

| 611,045

|

Massachusetts Avenue is ten blocks long. One boy and one girl live on each block. They want to form friendships such that each boy is friends with exactly one girl and viceversa. Nobody wants a friend living more than one block away (but they may be on the same block). How many pairings are possible?

|

89 Let $a_{n}$ be the number of pairings if there are $n$ blocks; we have $a_{1}=$ $1, a_{2}=2$, and we claim the Fibonacci recurrence is satisfied. Indeed, if there are $n$ blocks, either the boy on block 1 is friends with the girl on block 1, leaving $a_{n-1}$ possible pairings for the people on the remaining $n-1$ blocks, or he is friends with the girl on block 2 , in which case the girl on block 1 must be friends with the boy on block 2 , and then there are $a_{n-2}$ possibilities for the friendships among the remaining $n-2$ blocks. So $a_{n}=a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}$, and we compute: $a_{3}=3, a_{4}=5, \ldots, a_{10}=89$.

|

89

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Massachusetts Avenue is ten blocks long. One boy and one girl live on each block. They want to form friendships such that each boy is friends with exactly one girl and viceversa. Nobody wants a friend living more than one block away (but they may be on the same block). How many pairings are possible?

|

89 Let $a_{n}$ be the number of pairings if there are $n$ blocks; we have $a_{1}=$ $1, a_{2}=2$, and we claim the Fibonacci recurrence is satisfied. Indeed, if there are $n$ blocks, either the boy on block 1 is friends with the girl on block 1, leaving $a_{n-1}$ possible pairings for the people on the remaining $n-1$ blocks, or he is friends with the girl on block 2 , in which case the girl on block 1 must be friends with the boy on block 2 , and then there are $a_{n-2}$ possibilities for the friendships among the remaining $n-2$ blocks. So $a_{n}=a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}$, and we compute: $a_{3}=3, a_{4}=5, \ldots, a_{10}=89$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n38. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

b11806f8-b3d8-5de4-b7dc-546224e09806

| 611,046

|

In the $x-y$ plane, draw a circle of radius 2 centered at $(0,0)$. Color the circle red above the line $y=1$, color the circle blue below the line $y=-1$, and color the rest of the circle white. Now consider an arbitrary straight line at distance 1 from the circle. We color each point $P$ of the line with the color of the closest point to $P$ on the circle. If we pick such an arbitrary line, randomly oriented, what is the probability that it contains red, white, and blue points?

|

Let $O=(0,0), P=(1,0)$, and $H$ the foot of the perpendicular from $O$ to the line. If $\angle P O H$ (as measured counterclockwise) lies between $\pi / 3$ and $2 \pi / 3$, the line will fail to contain blue points; if it lies between $4 \pi / 3$ and $5 \pi / 3$, the line will fail to contain red points. Otherwise, it has points of every color. Thus, the answer is $1-\frac{2 \pi}{3} / 2 \pi=\frac{2}{3}$.

|

\frac{2}{3}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

In the $x-y$ plane, draw a circle of radius 2 centered at $(0,0)$. Color the circle red above the line $y=1$, color the circle blue below the line $y=-1$, and color the rest of the circle white. Now consider an arbitrary straight line at distance 1 from the circle. We color each point $P$ of the line with the color of the closest point to $P$ on the circle. If we pick such an arbitrary line, randomly oriented, what is the probability that it contains red, white, and blue points?

|

Let $O=(0,0), P=(1,0)$, and $H$ the foot of the perpendicular from $O$ to the line. If $\angle P O H$ (as measured counterclockwise) lies between $\pi / 3$ and $2 \pi / 3$, the line will fail to contain blue points; if it lies between $4 \pi / 3$ and $5 \pi / 3$, the line will fail to contain red points. Otherwise, it has points of every color. Thus, the answer is $1-\frac{2 \pi}{3} / 2 \pi=\frac{2}{3}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n39. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

ce3686cd-de38-581e-9f84-bb1c2ad121d2

| 611,047

|

Find the volume of the three-dimensional solid given by the inequality $\sqrt{x^{2}+y^{2}}+$ $|z| \leq 1$.

|

$2 \pi / 3$. The solid consists of two cones, one whose base is the circle $x^{2}+y^{2}=1$ in the $x y$-plane and whose vertex is $(0,0,1)$, and the other with the same base but vertex $(0,0,-1)$. Each cone has a base area of $\pi$ and a height of 1 , for a volume of $\pi / 3$, so the answer is $2 \pi / 3$.

|

\frac{2\pi}{3}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Find the volume of the three-dimensional solid given by the inequality $\sqrt{x^{2}+y^{2}}+$ $|z| \leq 1$.

|

$2 \pi / 3$. The solid consists of two cones, one whose base is the circle $x^{2}+y^{2}=1$ in the $x y$-plane and whose vertex is $(0,0,1)$, and the other with the same base but vertex $(0,0,-1)$. Each cone has a base area of $\pi$ and a height of 1 , for a volume of $\pi / 3$, so the answer is $2 \pi / 3$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n40. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

cbcc243e-3869-5c21-b4a0-7452c2cd1790

| 611,048

|

For any integer $n$, define $\lfloor n\rfloor$ as the greatest integer less than or equal to $n$. For any positive integer $n$, let

$$

f(n)=\lfloor n\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{3}\right\rfloor+\cdots+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{n}\right\rfloor .

$$

For how many values of $n, 1 \leq n \leq 100$, is $f(n)$ odd?

|

55 Notice that, for fixed $a,\lfloor n / a\rfloor$ counts the number of integers $b \in$ $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ which are divisible by $a$; hence, $f(n)$ counts the number of pairs $(a, b), a, b \in$ $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ with $b$ divisible by $a$. For any fixed $b$, the number of such pairs is $d(b)$ (the number of divisors of $b$ ), so the total number of pairs $f(n)$ equals $d(1)+d(2)+\cdots+d(n)$. But $d(b)$ is odd precisely when $b$ is a square, so $f(n)$ is odd precisely when there are an odd number of squares in $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$. This happens for $1 \leq n<4 ; 9 \leq n<16 ; \ldots ; 81 \leq n<100$. Adding these up gives 55 values of $n$.

|

55

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

For any integer $n$, define $\lfloor n\rfloor$ as the greatest integer less than or equal to $n$. For any positive integer $n$, let

$$

f(n)=\lfloor n\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{3}\right\rfloor+\cdots+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{n}\right\rfloor .

$$

For how many values of $n, 1 \leq n \leq 100$, is $f(n)$ odd?

|

55 Notice that, for fixed $a,\lfloor n / a\rfloor$ counts the number of integers $b \in$ $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ which are divisible by $a$; hence, $f(n)$ counts the number of pairs $(a, b), a, b \in$ $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ with $b$ divisible by $a$. For any fixed $b$, the number of such pairs is $d(b)$ (the number of divisors of $b$ ), so the total number of pairs $f(n)$ equals $d(1)+d(2)+\cdots+d(n)$. But $d(b)$ is odd precisely when $b$ is a square, so $f(n)$ is odd precisely when there are an odd number of squares in $\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$. This happens for $1 \leq n<4 ; 9 \leq n<16 ; \ldots ; 81 \leq n<100$. Adding these up gives 55 values of $n$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n41. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

15ef13db-ab71-5d2f-8816-f2634449487b

| 611,049

|

Given that $a, b, c$ are positive integers satisfying

$$

a+b+c=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+\operatorname{gcd}(b, c)+\operatorname{gcd}(c, a)+120

$$

determine the maximum possible value of $a$.

|

240. Notice that $(a, b, c)=(240,120,120)$ achieves a value of 240 . To see that this is maximal, first suppose that $a>b$. Notice that $a+b+c=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+\operatorname{gcd}(b, c)+$ $\operatorname{gcd}(c, a)+120 \leq \operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+b+c+120$, or $a \leq \operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+120$. However, $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$ is a proper divisor of $a$, so $a \geq 2 \cdot \operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$. Thus, $a-120 \leq \operatorname{gcd}(a, b) \leq a / 2$, yielding $a \leq 240$. Now, if instead $a \leq b$, then either $b>c$ and the same logic shows that $b \leq 240 \Rightarrow a \leq 240$, or $b \leq c, c>a$ (since $a, b, c$ cannot all be equal) and then $c \leq 240 \Rightarrow a \leq b \leq c \leq 240$.

|

240

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Given that $a, b, c$ are positive integers satisfying

$$

a+b+c=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+\operatorname{gcd}(b, c)+\operatorname{gcd}(c, a)+120

$$

determine the maximum possible value of $a$.

|

240. Notice that $(a, b, c)=(240,120,120)$ achieves a value of 240 . To see that this is maximal, first suppose that $a>b$. Notice that $a+b+c=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+\operatorname{gcd}(b, c)+$ $\operatorname{gcd}(c, a)+120 \leq \operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+b+c+120$, or $a \leq \operatorname{gcd}(a, b)+120$. However, $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$ is a proper divisor of $a$, so $a \geq 2 \cdot \operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$. Thus, $a-120 \leq \operatorname{gcd}(a, b) \leq a / 2$, yielding $a \leq 240$. Now, if instead $a \leq b$, then either $b>c$ and the same logic shows that $b \leq 240 \Rightarrow a \leq 240$, or $b \leq c, c>a$ (since $a, b, c$ cannot all be equal) and then $c \leq 240 \Rightarrow a \leq b \leq c \leq 240$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n43. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

f9affd7f-95ba-5c90-a5b4-f36f8f877839

| 611,051

|

The unknown real numbers $x, y, z$ satisfy the equations

$$

\frac{x+y}{1+z}=\frac{1-z+z^{2}}{x^{2}-x y+y^{2}} ; \quad \frac{x-y}{3-z}=\frac{9+3 z+z^{2}}{x^{2}+x y+y^{2}}

$$

Find $x$.

|

$\sqrt[3]{14}$ Cross-multiplying in both equations, we get, respectively, $x^{3}+y^{3}=$ $1+z^{3}, x^{3}-y^{3}=27-z^{3}$. Now adding gives $2 x^{3}=28$, or $x=\sqrt[3]{14}$.

|

\sqrt[3]{14}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

The unknown real numbers $x, y, z$ satisfy the equations

$$

\frac{x+y}{1+z}=\frac{1-z+z^{2}}{x^{2}-x y+y^{2}} ; \quad \frac{x-y}{3-z}=\frac{9+3 z+z^{2}}{x^{2}+x y+y^{2}}

$$

Find $x$.

|

$\sqrt[3]{14}$ Cross-multiplying in both equations, we get, respectively, $x^{3}+y^{3}=$ $1+z^{3}, x^{3}-y^{3}=27-z^{3}$. Now adding gives $2 x^{3}=28$, or $x=\sqrt[3]{14}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n44. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

b35100f5-12c4-597c-aaf9-28f29d77af44

| 611,052

|

Find the number of sequences $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{10}$ of positive integers with the property that $a_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+a_{n}$ for $n=1,2, \ldots, 8$, and $a_{10}=2002$.

|

3 Let $a_{1}=a, a_{2}=b$; we successively compute $a_{3}=a+b ; \quad a_{4}=a+$ $2 b ; \quad \ldots ; \quad a_{10}=21 a+34 b$. The equation $2002=21 a+34 b$ has three positive integer solutions, namely $(84,7),(50,28),(16,49)$, and each of these gives a unique sequence.

|

3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Find the number of sequences $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{10}$ of positive integers with the property that $a_{n+2}=a_{n+1}+a_{n}$ for $n=1,2, \ldots, 8$, and $a_{10}=2002$.

|

3 Let $a_{1}=a, a_{2}=b$; we successively compute $a_{3}=a+b ; \quad a_{4}=a+$ $2 b ; \quad \ldots ; \quad a_{10}=21 a+34 b$. The equation $2002=21 a+34 b$ has three positive integer solutions, namely $(84,7),(50,28),(16,49)$, and each of these gives a unique sequence.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n45. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

f48666ca-df41-5440-8cf4-a51882cb7d81

| 611,053

|

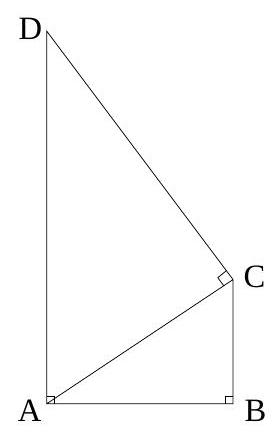

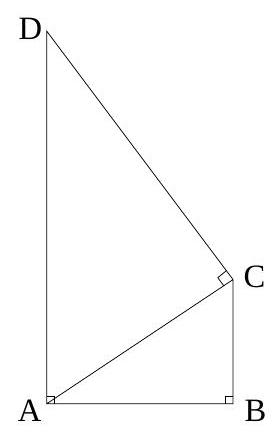

Points $A, B, C$ in the plane satisfy $\overline{A B}=2002, \overline{A C}=9999$. The circles with diameters $A B$ and $A C$ intersect at $A$ and $D$. If $\overline{A D}=37$, what is the shortest distance from point $A$ to line $B C$ ?

|

$\angle A D B=\angle A D C=\pi / 2$ since $D$ lies on the circles with $A B$ and $A C$ as diameters, so $D$ is the foot of the perpendicular from $A$ to line $B C$, and the answer is the given 37 .

|

37

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Points $A, B, C$ in the plane satisfy $\overline{A B}=2002, \overline{A C}=9999$. The circles with diameters $A B$ and $A C$ intersect at $A$ and $D$. If $\overline{A D}=37$, what is the shortest distance from point $A$ to line $B C$ ?

|

$\angle A D B=\angle A D C=\pi / 2$ since $D$ lies on the circles with $A B$ and $A C$ as diameters, so $D$ is the foot of the perpendicular from $A$ to line $B C$, and the answer is the given 37 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n46. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

8282c0ad-c243-5d66-8952-890b6be44f1c

| 611,054

|

The real function $f$ has the property that, whenever $a, b, n$ are positive integers such that $a+b=2^{n}$, the equation $f(a)+f(b)=n^{2}$ holds. What is $f(2002)$ ?

|

We know $f(a)=n^{2}-f\left(2^{n}-a\right)$ for any $a, n$ with $2^{n}>a$; repeated application gives

$$

\begin{gathered}

f(2002)=11^{2}-f(46)=11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-f(18)\right)=11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-\left(5^{2}-f(14)\right)\right) \\

=11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-\left(5^{2}-\left(4^{2}-f(2)\right)\right)\right) .

\end{gathered}

$$

But $f(2)=2^{2}-f(2)$, giving $f(2)=2$, so the above simplifies to $11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-\left(5^{2}-\left(4^{2}-\right.\right.\right.$ 2))) $=96$.

|

96

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

The real function $f$ has the property that, whenever $a, b, n$ are positive integers such that $a+b=2^{n}$, the equation $f(a)+f(b)=n^{2}$ holds. What is $f(2002)$ ?

|

We know $f(a)=n^{2}-f\left(2^{n}-a\right)$ for any $a, n$ with $2^{n}>a$; repeated application gives

$$

\begin{gathered}

f(2002)=11^{2}-f(46)=11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-f(18)\right)=11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-\left(5^{2}-f(14)\right)\right) \\

=11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-\left(5^{2}-\left(4^{2}-f(2)\right)\right)\right) .

\end{gathered}

$$

But $f(2)=2^{2}-f(2)$, giving $f(2)=2$, so the above simplifies to $11^{2}-\left(6^{2}-\left(5^{2}-\left(4^{2}-\right.\right.\right.$ 2))) $=96$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n47. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

d066e32f-fdf8-5ec6-9678-fd0f79436d4e

| 611,055

|

A permutation of a finite set is a one-to-one function from the set to itself; for instance, one permutation of $\{1,2,3,4\}$ is the function $\pi$ defined such that $\pi(1)=1, \pi(2)=3$, $\pi(3)=4$, and $\pi(4)=2$. How many permutations $\pi$ of the set $\{1,2, \ldots, 10\}$ have the property that $\pi(i) \neq i$ for each $i=1,2, \ldots, 10$, but $\pi(\pi(i))=i$ for each $i$ ?

|

For each such $\pi$, the elements of $\{1,2, \ldots, 10\}$ can be arranged into pairs $\{i, j\}$ such that $\pi(i)=j ; \pi(j)=i$. Choosing a permutation $\pi$ is thus tantamount to choosing a partition of $\{1,2, \ldots, 10\}$ into five disjoint pairs. There are 9 ways to pair off the number 1, then 7 ways to pair off the smallest number not yet paired, and so forth, so we have $9 \cdot 7 \cdot 5 \cdot 3 \cdot 1=945$ partitions into pairs.

|

945

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

A permutation of a finite set is a one-to-one function from the set to itself; for instance, one permutation of $\{1,2,3,4\}$ is the function $\pi$ defined such that $\pi(1)=1, \pi(2)=3$, $\pi(3)=4$, and $\pi(4)=2$. How many permutations $\pi$ of the set $\{1,2, \ldots, 10\}$ have the property that $\pi(i) \neq i$ for each $i=1,2, \ldots, 10$, but $\pi(\pi(i))=i$ for each $i$ ?

|

For each such $\pi$, the elements of $\{1,2, \ldots, 10\}$ can be arranged into pairs $\{i, j\}$ such that $\pi(i)=j ; \pi(j)=i$. Choosing a permutation $\pi$ is thus tantamount to choosing a partition of $\{1,2, \ldots, 10\}$ into five disjoint pairs. There are 9 ways to pair off the number 1, then 7 ways to pair off the smallest number not yet paired, and so forth, so we have $9 \cdot 7 \cdot 5 \cdot 3 \cdot 1=945$ partitions into pairs.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n48. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

d3d743d7-6ba0-5cca-afcf-ae4b28a020f5

| 611,056

|

Two integers are relatively prime if they don't share any common factors, i.e. if their greatest common divisor is 1 . Define $\varphi(n)$ as the number of positive integers that are less than $n$ and relatively prime to $n$. Define $\varphi_{d}(n)$ as the number of positive integers that are less than $d n$ and relatively prime to $n$.

What is the least $n$ such that $\varphi_{x}(n)=64000$, where $x=\varphi_{y}(n)$, where $y=\varphi(n)$ ?

|

For fixed $n$, the pattern of integers relatively prime to $n$ repeats every $n$ integers, so $\varphi_{d}(n)=d \varphi(n)$. Therefore the expression in the problem equals $\varphi(n)^{3}$. The cube root of 64000 is $40 . \varphi(p)=p-1$ for any prime $p$. Since 40 is one less than a prime, the least $n$ such that $\varphi(n)=40$ is 41 .

|

41

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Two integers are relatively prime if they don't share any common factors, i.e. if their greatest common divisor is 1 . Define $\varphi(n)$ as the number of positive integers that are less than $n$ and relatively prime to $n$. Define $\varphi_{d}(n)$ as the number of positive integers that are less than $d n$ and relatively prime to $n$.

What is the least $n$ such that $\varphi_{x}(n)=64000$, where $x=\varphi_{y}(n)$, where $y=\varphi(n)$ ?

|

For fixed $n$, the pattern of integers relatively prime to $n$ repeats every $n$ integers, so $\varphi_{d}(n)=d \varphi(n)$. Therefore the expression in the problem equals $\varphi(n)^{3}$. The cube root of 64000 is $40 . \varphi(p)=p-1$ for any prime $p$. Since 40 is one less than a prime, the least $n$ such that $\varphi(n)=40$ is 41 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n49. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

c91079b7-1c83-5c72-9dda-e72b461aedd5

| 611,057

|

Define $\varphi^{k}(n)$ as the number of positive integers that are less than or equal to $n / k$ and relatively prime to $n$. Find $\phi^{2001}\left(2002^{2}-1\right)$. (Hint: $\phi(2003)=2002$.)

|

$\varphi^{2001}\left(2002^{2}-1\right)=\varphi^{2001}(2001 \cdot 2003)=$ the number of $m$ that are relatively prime to both 2001 and 2003, where $m \leq 2003$. Since $\phi(n)=n-1$ implies that $n$ is prime, we must only check for those $m$ relatively prime to 2001, except for 2002, which is relatively prime to $2002^{2}-1$. So $\varphi^{2001}\left(2002^{2}-1\right)=\varphi(2001)+1=\varphi(3 \cdot 23 \cdot 29)+1=$ $(3-1)(23-1)(29-1)+1=1233$.

|

1233

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Define $\varphi^{k}(n)$ as the number of positive integers that are less than or equal to $n / k$ and relatively prime to $n$. Find $\phi^{2001}\left(2002^{2}-1\right)$. (Hint: $\phi(2003)=2002$.)

|

$\varphi^{2001}\left(2002^{2}-1\right)=\varphi^{2001}(2001 \cdot 2003)=$ the number of $m$ that are relatively prime to both 2001 and 2003, where $m \leq 2003$. Since $\phi(n)=n-1$ implies that $n$ is prime, we must only check for those $m$ relatively prime to 2001, except for 2002, which is relatively prime to $2002^{2}-1$. So $\varphi^{2001}\left(2002^{2}-1\right)=\varphi(2001)+1=\varphi(3 \cdot 23 \cdot 29)+1=$ $(3-1)(23-1)(29-1)+1=1233$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n51. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

9f1210d3-ea11-5284-8daf-8e509846903b

| 611,059

|

Let $A B C D$ be a quadrilateral, and let $E, F, G, H$ be the respective midpoints of $A B, B C, C D, D A$. If $E G=12$ and $F H=15$, what is the maximum possible area of $A B C D$ ?

|

The area of $E F G H$ is $E G \cdot F H \sin \theta / 2$, where $\theta$ is the angle between $E G$ and $F H$. This is at most 90 . However, we claim the area of $A B C D$ is twice that of $E F G H$. To see this, notice that $E F=A C / 2=G H, F G=B D / 2=H E$, so $E F G H$ is a parallelogram. The half of this parallelogram lying inside triangle $D A B$ has area $(B D / 2)(h / 2)$, where $h$ is the height from $A$ to $B D$, and triangle $D A B$ itself has area $B D \cdot h / 2=2 \cdot(B D / 2)(h / 2)$. A similar computation holds in triangle $B C D$, proving the claim. Thus, the area of $A B C D$ is at most 180. And this maximum is attainable - just take a rectangle with $A B=C D=$ $15, B C=D A=12$.

|

180

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a quadrilateral, and let $E, F, G, H$ be the respective midpoints of $A B, B C, C D, D A$. If $E G=12$ and $F H=15$, what is the maximum possible area of $A B C D$ ?

|

The area of $E F G H$ is $E G \cdot F H \sin \theta / 2$, where $\theta$ is the angle between $E G$ and $F H$. This is at most 90 . However, we claim the area of $A B C D$ is twice that of $E F G H$. To see this, notice that $E F=A C / 2=G H, F G=B D / 2=H E$, so $E F G H$ is a parallelogram. The half of this parallelogram lying inside triangle $D A B$ has area $(B D / 2)(h / 2)$, where $h$ is the height from $A$ to $B D$, and triangle $D A B$ itself has area $B D \cdot h / 2=2 \cdot(B D / 2)(h / 2)$. A similar computation holds in triangle $B C D$, proving the claim. Thus, the area of $A B C D$ is at most 180. And this maximum is attainable - just take a rectangle with $A B=C D=$ $15, B C=D A=12$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n52. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

2944aa69-18f1-5410-9b80-d345488e8e69

| 611,060

|

$A B C$ is a triangle with points $E, F$ on sides $A C, A B$, respectively. Suppose that $B E, C F$ intersect at $X$. It is given that $A F / F B=(A E / E C)^{2}$ and that $X$ is the midpoint of $B E$. Find the ratio $C X / X F$.

|

Let $x=A E / E C$. By Menelaus's theorem applied to triangle $A B E$ and line $C X F$,

$$

1=\frac{A F}{F B} \cdot \frac{B X}{X E} \cdot \frac{E C}{C A}=\frac{x^{2}}{x+1} .

$$

Thus, $x^{2}=x+1$, and $x$ must be positive, so $x=(1+\sqrt{5}) / 2$. Now apply Menelaus to triangle $A C F$ and line $B X E$, obtaining

$$

1=\frac{A E}{E C} \cdot \frac{C X}{X F} \cdot \frac{F B}{B A}=\frac{C X}{X F} \cdot \frac{x}{x^{2}+1},

$$

so $C X / X F=\left(x^{2}+1\right) / x=\left(2 x^{2}-x\right) / x=2 x-1=\sqrt{5}$.

|

\sqrt{5}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

$A B C$ is a triangle with points $E, F$ on sides $A C, A B$, respectively. Suppose that $B E, C F$ intersect at $X$. It is given that $A F / F B=(A E / E C)^{2}$ and that $X$ is the midpoint of $B E$. Find the ratio $C X / X F$.

|

Let $x=A E / E C$. By Menelaus's theorem applied to triangle $A B E$ and line $C X F$,

$$

1=\frac{A F}{F B} \cdot \frac{B X}{X E} \cdot \frac{E C}{C A}=\frac{x^{2}}{x+1} .

$$

Thus, $x^{2}=x+1$, and $x$ must be positive, so $x=(1+\sqrt{5}) / 2$. Now apply Menelaus to triangle $A C F$ and line $B X E$, obtaining

$$

1=\frac{A E}{E C} \cdot \frac{C X}{X F} \cdot \frac{F B}{B A}=\frac{C X}{X F} \cdot \frac{x}{x^{2}+1},

$$

so $C X / X F=\left(x^{2}+1\right) / x=\left(2 x^{2}-x\right) / x=2 x-1=\sqrt{5}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n53. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

f38c1584-b1f6-556e-b020-467df73115a6

| 611,061

|

How many pairs of integers $(a, b)$, with $1 \leq a \leq b \leq 60$, have the property that $b$ is divisible by $a$ and $b+1$ is divisible by $a+1$ ?

|

The divisibility condition is equivalent to $b-a$ being divisible by both $a$ and $a+1$, or, equivalently (since these are relatively prime), by $a(a+1)$. Any $b$ satisfying the condition is automatically $\geq a$, so it suffices to count the number of values $b-a \in$ $\{1-a, 2-a, \ldots, 60-a\}$ that are divisible by $a(a+1)$ and sum over all $a$. The number of such values will be precisely $60 /[a(a+1)]$ whenever this quantity is an integer, which fortunately happens for every $a \leq 5$; we count:

$a=1$ gives 30 values of $b$;

$a=2$ gives 10 values of $b$;

$a=3$ gives 5 values of $b$;

$a=4$ gives 3 values of $b$;

$a=5$ gives 2 values of $b$;

$a=6$ gives 2 values ( $b=6$ or 48);

any $a \geq 7$ gives only one value, namely $b=a$, since $b>a$ implies $b \geq a+a(a+1)>60$.

Adding these up, we get a total of 106 pairs.

|

106

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

How many pairs of integers $(a, b)$, with $1 \leq a \leq b \leq 60$, have the property that $b$ is divisible by $a$ and $b+1$ is divisible by $a+1$ ?

|

The divisibility condition is equivalent to $b-a$ being divisible by both $a$ and $a+1$, or, equivalently (since these are relatively prime), by $a(a+1)$. Any $b$ satisfying the condition is automatically $\geq a$, so it suffices to count the number of values $b-a \in$ $\{1-a, 2-a, \ldots, 60-a\}$ that are divisible by $a(a+1)$ and sum over all $a$. The number of such values will be precisely $60 /[a(a+1)]$ whenever this quantity is an integer, which fortunately happens for every $a \leq 5$; we count:

$a=1$ gives 30 values of $b$;

$a=2$ gives 10 values of $b$;

$a=3$ gives 5 values of $b$;

$a=4$ gives 3 values of $b$;

$a=5$ gives 2 values of $b$;

$a=6$ gives 2 values ( $b=6$ or 48);

any $a \geq 7$ gives only one value, namely $b=a$, since $b>a$ implies $b \geq a+a(a+1)>60$.

Adding these up, we get a total of 106 pairs.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n54. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

f894f36b-163c-5782-96d3-3adf75e52e9e

| 611,062

|

A sequence of positive integers is given by $a_{1}=1$ and $a_{n}=\operatorname{gcd}\left(a_{n-1}, n\right)+1$ for $n>1$. Calculate $a_{2002}$.

|

3. It is readily seen by induction that $a_{n} \leq n$ for all $n$. On the other hand, $a_{1999}$ is one greater than a divisor of 1999. Since 1999 is prime, we have $a_{1999}=2$ or 2000; the latter is not possible since $2000>1999$, so we have $a_{1999}=2$. Now we straightforwardly compute $a_{2000}=3, a_{2001}=4$, and $a_{2002}=3$.

|

3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

A sequence of positive integers is given by $a_{1}=1$ and $a_{n}=\operatorname{gcd}\left(a_{n-1}, n\right)+1$ for $n>1$. Calculate $a_{2002}$.

|

3. It is readily seen by induction that $a_{n} \leq n$ for all $n$. On the other hand, $a_{1999}$ is one greater than a divisor of 1999. Since 1999 is prime, we have $a_{1999}=2$ or 2000; the latter is not possible since $2000>1999$, so we have $a_{1999}=2$. Now we straightforwardly compute $a_{2000}=3, a_{2001}=4$, and $a_{2002}=3$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n55. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

5a07ee50-435a-5789-a0e4-b73e53ba7704

| 611,063

|

$x, y$ are positive real numbers such that $x+y^{2}=x y$. What is the smallest possible value of $x$ ?

|

4 Notice that $x=y^{2} /(y-1)=2+(y-1)+1 /(y-1) \geq 2+2=4$. Conversely, $x=4$ is achievable, by taking $y=2$.

|

4

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

$x, y$ are positive real numbers such that $x+y^{2}=x y$. What is the smallest possible value of $x$ ?

|

4 Notice that $x=y^{2} /(y-1)=2+(y-1)+1 /(y-1) \geq 2+2=4$. Conversely, $x=4$ is achievable, by taking $y=2$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n56. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

9e1077c7-756c-5b4f-b157-7b85fbd1a35c

| 611,064

|

How many ways, without taking order into consideration, can 2002 be expressed as the sum of 3 positive integers (for instance, $1000+1000+2$ and $1000+2+1000$ are considered to be the same way)?

|

Call the three numbers that sum to $2002 A, B$, and $C$. In order to prevent redundancy, we will consider only cases where $A \leq B \leq C$. Then $A$ can range from 1 to 667 , inclusive. For odd $A$, there are $1000-\frac{3(A-1)}{2}$ possible values for $B$. For each choice of $A$ and $B$, there can only be one possible $C$, since the three numbers must add up to a fixed value. We can add up this arithmetic progression to find that there are 167167 possible combinations of $A, B, C$, for odd $A$. For each even $A$, there are $1002-\frac{3 A}{2}$ possible values for $B$. Therefore, there are 166833 possible combinations for even $A$. In total, this makes 334000 possibilities.

|

334000

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

How many ways, without taking order into consideration, can 2002 be expressed as the sum of 3 positive integers (for instance, $1000+1000+2$ and $1000+2+1000$ are considered to be the same way)?

|

Call the three numbers that sum to $2002 A, B$, and $C$. In order to prevent redundancy, we will consider only cases where $A \leq B \leq C$. Then $A$ can range from 1 to 667 , inclusive. For odd $A$, there are $1000-\frac{3(A-1)}{2}$ possible values for $B$. For each choice of $A$ and $B$, there can only be one possible $C$, since the three numbers must add up to a fixed value. We can add up this arithmetic progression to find that there are 167167 possible combinations of $A, B, C$, for odd $A$. For each even $A$, there are $1002-\frac{3 A}{2}$ possible values for $B$. Therefore, there are 166833 possible combinations for even $A$. In total, this makes 334000 possibilities.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n57. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

dab6414f-9502-5749-b4ad-d00ffc165814

| 611,065

|

A sequence is defined by $a_{0}=1$ and $a_{n}=2^{a_{n-1}}$ for $n \geq 1$. What is the last digit (in base 10) of $a_{15}$ ?

|

6. Certainly $a_{13} \geq 2$, so $a_{14}$ is divisible by $2^{2}=4$. Writing $a_{14}=4 k$, we have $a_{15}=2^{4 k}=16^{k}$. But every power of 16 ends in 6 , so this is the answer.

|

6

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

A sequence is defined by $a_{0}=1$ and $a_{n}=2^{a_{n-1}}$ for $n \geq 1$. What is the last digit (in base 10) of $a_{15}$ ?

|

6. Certainly $a_{13} \geq 2$, so $a_{14}$ is divisible by $2^{2}=4$. Writing $a_{14}=4 k$, we have $a_{15}=2^{4 k}=16^{k}$. But every power of 16 ends in 6 , so this is the answer.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n58. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

83372dc1-d990-5845-bef8-f3f0f9b3499a

| 611,066

|

Determine the value of

$$

1 \cdot 2-2 \cdot 3+3 \cdot 4-4 \cdot 5+\cdots+2001 \cdot 2002 .

$$

|

2004002. Rewrite the expression as

$$

2+3 \cdot(4-2)+5 \cdot(6-4)+\cdots+2001 \cdot(2002-2000)

$$

$$

=2+6+10+\cdots+4002 .

$$

This is an arithmetic progression with $(4002-2) / 4+1=1001$ terms and average 2002, so its sum is $1001 \cdot 2002=2004002$.

|

2004002

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Determine the value of

$$

1 \cdot 2-2 \cdot 3+3 \cdot 4-4 \cdot 5+\cdots+2001 \cdot 2002 .

$$

|

2004002. Rewrite the expression as

$$

2+3 \cdot(4-2)+5 \cdot(6-4)+\cdots+2001 \cdot(2002-2000)

$$

$$

=2+6+10+\cdots+4002 .

$$

This is an arithmetic progression with $(4002-2) / 4+1=1001$ terms and average 2002, so its sum is $1001 \cdot 2002=2004002$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n59. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

eadfbd18-fddc-54fa-81e0-adc38c53c441

| 611,067

|

A $5 \times 5$ square grid has the number -3 written in the upper-left square and the number 3 written in the lower-right square. In how many ways can the remaining squares be filled in with integers so that any two adjacent numbers differ by 1 , where two squares are adjacent if they share a common edge (but not if they share only a corner)?

|

250 If the square in row $i$, column $j$ contains the number $k$, let its "index" be $i+j-k$. The constraint on adjacent squares now says that if a square has index $r$, the squares to its right and below it each have index $r$ or $r+2$. The upper-left square has index 5 , and the lower-right square has index 7 , so every square must have index 5 or 7 . The boundary separating the two types of squares is a path consisting of upward and rightward steps; it can be extended along the grid's border so as to obtain a path between the lower-left and upper-right corners. Conversely, any such path uniquely determines each square's index and hence the entire array of numbers - except that the two paths lying entirely along the border of the grid fail to separate the upper-left from the lower-right square and thus do not create valid arrays (since these two squares should have different indices). Each path consists of 5 upward and 5 rightward steps, so there are $\binom{10}{5}=252$ paths, but two are impossible, so the answer is 250 .

|

250

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

A $5 \times 5$ square grid has the number -3 written in the upper-left square and the number 3 written in the lower-right square. In how many ways can the remaining squares be filled in with integers so that any two adjacent numbers differ by 1 , where two squares are adjacent if they share a common edge (but not if they share only a corner)?

|

250 If the square in row $i$, column $j$ contains the number $k$, let its "index" be $i+j-k$. The constraint on adjacent squares now says that if a square has index $r$, the squares to its right and below it each have index $r$ or $r+2$. The upper-left square has index 5 , and the lower-right square has index 7 , so every square must have index 5 or 7 . The boundary separating the two types of squares is a path consisting of upward and rightward steps; it can be extended along the grid's border so as to obtain a path between the lower-left and upper-right corners. Conversely, any such path uniquely determines each square's index and hence the entire array of numbers - except that the two paths lying entirely along the border of the grid fail to separate the upper-left from the lower-right square and thus do not create valid arrays (since these two squares should have different indices). Each path consists of 5 upward and 5 rightward steps, so there are $\binom{10}{5}=252$ paths, but two are impossible, so the answer is 250 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n60. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

55e0f4b1-ffce-5b67-a4ac-101fb21936fc

| 611,068

|

Bob Barker went back to school for a PhD in math, and decided to raise the intellectual level of The Price is Right by having contestants guess how many objects exist of a certain type, without going over. The number of points you will get is the percentage of the correct answer, divided by 10 , with no points for going over (i.e. a maximum of 10 points).

Let's see the first object for our contestants...a table of shape (5, 4, 3, 2, 1) is an arrangement of the integers 1 through 15 with five numbers in the top row, four in the next, three in the next, two in the next, and one in the last, such that each row and each column is increasing (from left to right, and top to bottom, respectively). For instance:

```

1

6

10 11 12

13 14

15

```

is one table. How many tables are there?

|

$15!/\left(3^{4} \cdot 5^{3} \cdot 7^{2} \cdot 9\right)=292864$. These are Standard Young Tableaux.

|

292864

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Bob Barker went back to school for a PhD in math, and decided to raise the intellectual level of The Price is Right by having contestants guess how many objects exist of a certain type, without going over. The number of points you will get is the percentage of the correct answer, divided by 10 , with no points for going over (i.e. a maximum of 10 points).

Let's see the first object for our contestants...a table of shape (5, 4, 3, 2, 1) is an arrangement of the integers 1 through 15 with five numbers in the top row, four in the next, three in the next, two in the next, and one in the last, such that each row and each column is increasing (from left to right, and top to bottom, respectively). For instance:

```

1

6

10 11 12

13 14

15

```

is one table. How many tables are there?

|

$15!/\left(3^{4} \cdot 5^{3} \cdot 7^{2} \cdot 9\right)=292864$. These are Standard Young Tableaux.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n61. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

93c09ce1-8bed-56a1-ba0a-c02a94316e64

| 611,069

|

Our next object up for bid is an arithmetic progression of primes. For example, the primes 3,5 , and 7 form an arithmetic progression of length 3 . What is the largest possible length of an arithmetic progression formed of positive primes less than $1,000,000$ ? Be prepared to justify your answer.

|

12 . We can get 12 with 110437 and difference 13860 .

|

12

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Our next object up for bid is an arithmetic progression of primes. For example, the primes 3,5 , and 7 form an arithmetic progression of length 3 . What is the largest possible length of an arithmetic progression formed of positive primes less than $1,000,000$ ? Be prepared to justify your answer.

|

12 . We can get 12 with 110437 and difference 13860 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-52-2002-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n62. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

fe810f6d-f12a-5612-ab2c-dca11fe8a5a6

| 611,070

|

Our third and final item comes to us from Germany, I mean Geometry. It is known that a regular $n$-gon can be constructed with straightedge and compass if $n$ is a prime that is 1 plus a power of 2 . It is also possible to construct a $2 n$-gon whenever an $n$-gon is constructible, or a $p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{m}$-gon where the $p_{i}$ 's are distinct primes of the above form. What is really interesting is that these conditions, together with the fact that we can construct a square, is that they give us all constructible regular $n$-gons. What is the largest $n$ less than $4,300,000,000$ such that a regular $n$-gon is constructible?

|