problem

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution

stringlengths 3

10k

| answer

stringlengths 1

91

| problem_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 1

value | question_type

stringclasses 1

value | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

7.96k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 3

10k

| metadata

dict | uuid

stringlengths 36

36

| id

int64 22.6k

612k

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Augustin has six $1 \times 2 \times \pi$ bricks. He stacks them, one on top of another, to form a tower six bricks high. Each brick can be in any orientation so long as it rests flat on top of the next brick below it (or on the floor). How many distinct heights of towers can he make?

|

28

If there are $k$ bricks which are placed so that they contribute either 1 or 2 height, then the height of these $k$ bricks can be any integer from $k$ to $2 k$. Furthermore, towers with different values of $k$ cannot have the same height. Thus, for each $k$ there are $k+1$ possible tower heights, and since $k$ is any integer from 0 to 6 , there are $1+2+3+4+5+6+7=28$ possible heights.

|

28

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Augustin has six $1 \times 2 \times \pi$ bricks. He stacks them, one on top of another, to form a tower six bricks high. Each brick can be in any orientation so long as it rests flat on top of the next brick below it (or on the floor). How many distinct heights of towers can he make?

|

28

If there are $k$ bricks which are placed so that they contribute either 1 or 2 height, then the height of these $k$ bricks can be any integer from $k$ to $2 k$. Furthermore, towers with different values of $k$ cannot have the same height. Thus, for each $k$ there are $k+1$ possible tower heights, and since $k$ is any integer from 0 to 6 , there are $1+2+3+4+5+6+7=28$ possible heights.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n5. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

7e8324e8-385e-56f2-bf9e-7f41ee8bbbd3

| 611,247

|

Find the smallest integer $n$ such that $\sqrt{n+99}-\sqrt{n}<1$.

|

2402

This is equivalent to

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sqrt{n+99} & <\sqrt{n}+1 \\

n+99 & <n+1+2 \sqrt{n} \\

49 & <\sqrt{n}

\end{aligned}

$$

So the smallest integer $n$ with this property is $49^{2}+1=2402$.

|

2402

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Inequalities

|

Find the smallest integer $n$ such that $\sqrt{n+99}-\sqrt{n}<1$.

|

2402

This is equivalent to

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sqrt{n+99} & <\sqrt{n}+1 \\

n+99 & <n+1+2 \sqrt{n} \\

49 & <\sqrt{n}

\end{aligned}

$$

So the smallest integer $n$ with this property is $49^{2}+1=2402$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n6. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

9d27788d-fd99-5a8d-b126-293d217a55b9

| 611,248

|

Find the shortest distance from the line $3 x+4 y=25$ to the circle $x^{2}+y^{2}=6 x-8 y$.

|

$7 / 5$

The circle is $(x-3)^{2}+(y+4)^{2}=5^{2}$. The center $(3,-4)$ is a distance of

$$

\frac{|3 \cdot 3+4 \cdot-4-25|}{\sqrt{3^{2}+4^{2}}}=\frac{32}{5}

$$

from the line, so we subtract 5 for the radius of the circle and get $7 / 5$.

|

\frac{7}{5}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Find the shortest distance from the line $3 x+4 y=25$ to the circle $x^{2}+y^{2}=6 x-8 y$.

|

$7 / 5$

The circle is $(x-3)^{2}+(y+4)^{2}=5^{2}$. The center $(3,-4)$ is a distance of

$$

\frac{|3 \cdot 3+4 \cdot-4-25|}{\sqrt{3^{2}+4^{2}}}=\frac{32}{5}

$$

from the line, so we subtract 5 for the radius of the circle and get $7 / 5$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n7. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

8f654c5b-6f68-56e7-b354-adb75e837564

| 611,249

|

I have chosen five of the numbers $\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7\}$. If I told you what their product was, that would not be enough information for you to figure out whether their sum was even or odd. What is their product?

|

420

Giving you the product of the five numbers is equivalent to telling you the product of the two numbers I didn't choose. The only possible products that are achieved by more than one pair of numbers are $12(\{3,4\}$ and $\{2,6\})$ and $6(\{1,6\}$ and $\{2,3\})$. But in the second case, you at least know that the two unchosen numbers have odd sum (and so the five chosen numbers have odd sum also). Therefore, the first case must hold, and the product of the five chosen numbers is

$$

1 \cdot 2 \cdot 5 \cdot 6 \cdot 7=1 \cdot 3 \cdot 4 \cdot 5 \cdot 7=420

$$

|

420

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

I have chosen five of the numbers $\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7\}$. If I told you what their product was, that would not be enough information for you to figure out whether their sum was even or odd. What is their product?

|

420

Giving you the product of the five numbers is equivalent to telling you the product of the two numbers I didn't choose. The only possible products that are achieved by more than one pair of numbers are $12(\{3,4\}$ and $\{2,6\})$ and $6(\{1,6\}$ and $\{2,3\})$. But in the second case, you at least know that the two unchosen numbers have odd sum (and so the five chosen numbers have odd sum also). Therefore, the first case must hold, and the product of the five chosen numbers is

$$

1 \cdot 2 \cdot 5 \cdot 6 \cdot 7=1 \cdot 3 \cdot 4 \cdot 5 \cdot 7=420

$$

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n8. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

1c0da341-2889-542c-adb8-044490a45ea7

| 611,250

|

A positive integer $n$ is picante if $n$ ! ends in the same number of zeroes whether written in base 7 or in base 8 . How many of the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 2004$ are picante?

|

4

The number of zeroes in base 7 is the total number of factors of 7 in $1 \cdot 2 \cdots n$, which is

$$

\lfloor n / 7\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 7^{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 7^{3}\right\rfloor+\cdots .

$$

The number of zeroes in base 8 is $\lfloor a\rfloor$, where

$$

a=\left(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 2^{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 2^{3}\right\rfloor+\cdots\right) / 3

$$

is one-third the number of factors of 2 in the product $n$ !. Now $\left\lfloor n / 2^{k}\right\rfloor / 3 \geq\left\lfloor n / 7^{k}\right\rfloor$ for all $k$, since $\left(n / 2^{k}\right) / 3 \geq n / 7^{k}$. But $n$ can only be picante if the two sums differ by at most $2 / 3$, so in particular this requires $\left(\left\lfloor n / 2^{2}\right\rfloor\right) / 3 \leq\left\lfloor n / 7^{2}\right\rfloor+2 / 3 \Leftrightarrow\lfloor n / 4\rfloor \leq 3\lfloor n / 49\rfloor+2$. This cannot happen for $n \geq 12$; checking the remaining few cases by hand, we find $n=1,2,3,7$ are picante, for a total of 4 values.

|

4

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

A positive integer $n$ is picante if $n$ ! ends in the same number of zeroes whether written in base 7 or in base 8 . How many of the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 2004$ are picante?

|

4

The number of zeroes in base 7 is the total number of factors of 7 in $1 \cdot 2 \cdots n$, which is

$$

\lfloor n / 7\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 7^{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 7^{3}\right\rfloor+\cdots .

$$

The number of zeroes in base 8 is $\lfloor a\rfloor$, where

$$

a=\left(\lfloor n / 2\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 2^{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor n / 2^{3}\right\rfloor+\cdots\right) / 3

$$

is one-third the number of factors of 2 in the product $n$ !. Now $\left\lfloor n / 2^{k}\right\rfloor / 3 \geq\left\lfloor n / 7^{k}\right\rfloor$ for all $k$, since $\left(n / 2^{k}\right) / 3 \geq n / 7^{k}$. But $n$ can only be picante if the two sums differ by at most $2 / 3$, so in particular this requires $\left(\left\lfloor n / 2^{2}\right\rfloor\right) / 3 \leq\left\lfloor n / 7^{2}\right\rfloor+2 / 3 \Leftrightarrow\lfloor n / 4\rfloor \leq 3\lfloor n / 49\rfloor+2$. This cannot happen for $n \geq 12$; checking the remaining few cases by hand, we find $n=1,2,3,7$ are picante, for a total of 4 values.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n9. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

02ff864a-46f7-52f3-aeb0-c24102a2fc74

| 611,251

|

Let $f(x)=x^{2}+x^{4}+x^{6}+x^{8}+\cdots$, for all real $x$ such that the sum converges. For how many real numbers $x$ does $f(x)=x$ ?

|

2

Clearly $x=0$ works. Otherwise, we want $x=x^{2} /\left(1-x^{2}\right)$, or $x^{2}+x-1=0$. Discard the negative root (since the sum doesn't converge there), but $(-1+\sqrt{5}) / 2$ works, for a total of 2 values.

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $f(x)=x^{2}+x^{4}+x^{6}+x^{8}+\cdots$, for all real $x$ such that the sum converges. For how many real numbers $x$ does $f(x)=x$ ?

|

2

Clearly $x=0$ works. Otherwise, we want $x=x^{2} /\left(1-x^{2}\right)$, or $x^{2}+x-1=0$. Discard the negative root (since the sum doesn't converge there), but $(-1+\sqrt{5}) / 2$ works, for a total of 2 values.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n10. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

c2f717a2-ba68-5335-81bd-fd80c9c7c74f

| 611,252

|

A convex quadrilateral is drawn in the coordinate plane such that each of its vertices $(x, y)$ satisfies the equations $x^{2}+y^{2}=73$ and $x y=24$. What is the area of this quadrilateral?

|

110

The vertices all satisfy $(x+y)^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}+2 x y=73+2 \cdot 24=121$, so $x+y= \pm 11$. Similarly, $(x-y)^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}-2 x y=73-2 \cdot 24=25$, so $x-y= \pm 5$. Thus, there are four solutions: $(x, y)=(8,3),(3,8),(-3,-8),(-8,-3)$. All four of these solutions satisfy the original equations. The quadrilateral is therefore a rectangle with side lengths of $5 \sqrt{2}$ and $11 \sqrt{2}$, so its area is 110 .

|

110

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A convex quadrilateral is drawn in the coordinate plane such that each of its vertices $(x, y)$ satisfies the equations $x^{2}+y^{2}=73$ and $x y=24$. What is the area of this quadrilateral?

|

110

The vertices all satisfy $(x+y)^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}+2 x y=73+2 \cdot 24=121$, so $x+y= \pm 11$. Similarly, $(x-y)^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}-2 x y=73-2 \cdot 24=25$, so $x-y= \pm 5$. Thus, there are four solutions: $(x, y)=(8,3),(3,8),(-3,-8),(-8,-3)$. All four of these solutions satisfy the original equations. The quadrilateral is therefore a rectangle with side lengths of $5 \sqrt{2}$ and $11 \sqrt{2}$, so its area is 110 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n12. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

7f8d42e1-10fe-5e10-be87-ec8728e03236

| 611,254

|

If $a_{1}=1, a_{2}=0$, and $a_{n+1}=a_{n}+\frac{a_{n+2}}{2}$ for all $n \geq 1$, compute $a_{2004}$.

|

$\quad-2^{1002}$

By writing out the first few terms, we find that $a_{n+4}=-4 a_{n}$. Indeed,

$$

a_{n+4}=2\left(a_{n+3}-a_{n+2}\right)=2\left(a_{n+2}-2 a_{n+1}\right)=2\left(-2 a_{n}\right)=-4 a_{n} .

$$

Then, by induction, we get $a_{4 k}=(-4)^{k}$ for all positive integers $k$, and setting $k=501$ gives the answer.

|

-2^{1002}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

If $a_{1}=1, a_{2}=0$, and $a_{n+1}=a_{n}+\frac{a_{n+2}}{2}$ for all $n \geq 1$, compute $a_{2004}$.

|

$\quad-2^{1002}$

By writing out the first few terms, we find that $a_{n+4}=-4 a_{n}$. Indeed,

$$

a_{n+4}=2\left(a_{n+3}-a_{n+2}\right)=2\left(a_{n+2}-2 a_{n+1}\right)=2\left(-2 a_{n}\right)=-4 a_{n} .

$$

Then, by induction, we get $a_{4 k}=(-4)^{k}$ for all positive integers $k$, and setting $k=501$ gives the answer.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n14. ",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution: "

}

|

0bb338af-74e2-5d08-9434-ec4dab3cc3a5

| 611,256

|

An $n$-string is a string of digits formed by writing the numbers $1,2, \ldots, n$ in some order (in base ten). For example, one possible 10-string is

35728910461

What is the smallest $n>1$ such that there exists a palindromic $n$-string?

|

The following is such a string for $n=19$ :

$$

9|18| 7|16| 5|14| 3|12| 1|10| 11|2| 13|4| 15|6| 17|8| 19

$$

where the vertical bars indicate breaks between the numbers. On the other hand, to see that $n=19$ is the minimum, notice that only one digit can occur an odd number of times in a palindromic $n$-string (namely the center digit). If $n \leq 9$, then (say) the digits 1,2 each appear once in any $n$-string, so we cannot have a palindrome. If $10 \leq n \leq 18$, then 0,9 each appear once, and we again cannot have a palindrome. So 19 is the smallest possible $n$.

|

19

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

An $n$-string is a string of digits formed by writing the numbers $1,2, \ldots, n$ in some order (in base ten). For example, one possible 10-string is

35728910461

What is the smallest $n>1$ such that there exists a palindromic $n$-string?

|

The following is such a string for $n=19$ :

$$

9|18| 7|16| 5|14| 3|12| 1|10| 11|2| 13|4| 15|6| 17|8| 19

$$

where the vertical bars indicate breaks between the numbers. On the other hand, to see that $n=19$ is the minimum, notice that only one digit can occur an odd number of times in a palindromic $n$-string (namely the center digit). If $n \leq 9$, then (say) the digits 1,2 each appear once in any $n$-string, so we cannot have a palindrome. If $10 \leq n \leq 18$, then 0,9 each appear once, and we again cannot have a palindrome. So 19 is the smallest possible $n$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n16. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:\n"

}

|

da8aeffd-a84e-5397-b499-668bec89f79d

| 611,258

|

Kate has four red socks and four blue socks. If she randomly divides these eight socks into four pairs, what is the probability that none of the pairs will be mismatched? That is, what is the probability that each pair will consist either of two red socks or of two blue socks?

|

$3 / 35$

The number of ways Kate can divide the four red socks into two pairs is $\binom{4}{2} / 2=3$. The number of ways she can divide the four blue socks into two pairs is also 3 . Therefore, the number of ways she can form two pairs of red socks and two pairs of blue socks is

$3 \cdot 3=9$. The total number of ways she can divide the eight socks into four pairs is $[8!/(2!\cdot 2!\cdot 2!\cdot 2!)] / 4!=105$, so the probability that the socks come out paired correctly is $9 / 105=3 / 35$.

To see why 105 is the correct denominator, we can look at each 2 ! term as representing the double counting of pair $(a b)$ and pair ( $b a$ ), while the 4 ! term represents the number of different orders in which we can select the same four pairs. Alternatively, we know that there are three ways to select two pairs from four socks. To select three pairs from six socks, there are five different choices for the first sock's partner and then three ways to pair up the remaining four socks, for a total of $5 \cdot 3=15$ pairings. To select four pairs from eight socks, there are seven different choices for the first sock's partner and then fifteen ways to pair up the remaining six socks, for a total of $7 \cdot 15=105$ pairings.

|

\frac{3}{35}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Kate has four red socks and four blue socks. If she randomly divides these eight socks into four pairs, what is the probability that none of the pairs will be mismatched? That is, what is the probability that each pair will consist either of two red socks or of two blue socks?

|

$3 / 35$

The number of ways Kate can divide the four red socks into two pairs is $\binom{4}{2} / 2=3$. The number of ways she can divide the four blue socks into two pairs is also 3 . Therefore, the number of ways she can form two pairs of red socks and two pairs of blue socks is

$3 \cdot 3=9$. The total number of ways she can divide the eight socks into four pairs is $[8!/(2!\cdot 2!\cdot 2!\cdot 2!)] / 4!=105$, so the probability that the socks come out paired correctly is $9 / 105=3 / 35$.

To see why 105 is the correct denominator, we can look at each 2 ! term as representing the double counting of pair $(a b)$ and pair ( $b a$ ), while the 4 ! term represents the number of different orders in which we can select the same four pairs. Alternatively, we know that there are three ways to select two pairs from four socks. To select three pairs from six socks, there are five different choices for the first sock's partner and then three ways to pair up the remaining four socks, for a total of $5 \cdot 3=15$ pairings. To select four pairs from eight socks, there are seven different choices for the first sock's partner and then fifteen ways to pair up the remaining six socks, for a total of $7 \cdot 15=105$ pairings.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n17. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

f3925d60-8199-5a27-843c-518d7cedf9d4

| 611,259

|

The Fibonacci numbers are defined by $F_{1}=F_{2}=1$, and $F_{n}=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2}$ for $n \geq 3$. If the number

$$

\frac{F_{2003}}{F_{2002}}-\frac{F_{2004}}{F_{2003}}

$$

is written as a fraction in lowest terms, what is the numerator?

|

1

Before reducing, the numerator is $F_{2003}^{2}-F_{2002} F_{2004}$. We claim $F_{n}^{2}-F_{n-1} F_{n+1}=$ $(-1)^{n+1}$, which will immediately imply that the answer is 1 (no reducing required). This claim is straightforward to prove by induction on $n$ : it holds for $n=2$, and if it holds for some $n$, then

$F_{n+1}^{2}-F_{n} F_{n+2}=F_{n+1}\left(F_{n-1}+F_{n}\right)-F_{n}\left(F_{n}+F_{n+1}\right)=F_{n+1} F_{n-1}-F_{n}^{2}=-(-1)^{n+1}=(-1)^{n+2}$.

|

1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

The Fibonacci numbers are defined by $F_{1}=F_{2}=1$, and $F_{n}=F_{n-1}+F_{n-2}$ for $n \geq 3$. If the number

$$

\frac{F_{2003}}{F_{2002}}-\frac{F_{2004}}{F_{2003}}

$$

is written as a fraction in lowest terms, what is the numerator?

|

1

Before reducing, the numerator is $F_{2003}^{2}-F_{2002} F_{2004}$. We claim $F_{n}^{2}-F_{n-1} F_{n+1}=$ $(-1)^{n+1}$, which will immediately imply that the answer is 1 (no reducing required). This claim is straightforward to prove by induction on $n$ : it holds for $n=2$, and if it holds for some $n$, then

$F_{n+1}^{2}-F_{n} F_{n+2}=F_{n+1}\left(F_{n-1}+F_{n}\right)-F_{n}\left(F_{n}+F_{n+1}\right)=F_{n+1} F_{n-1}-F_{n}^{2}=-(-1)^{n+1}=(-1)^{n+2}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n19. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

dc904e62-4f77-5f70-b24c-98c793d5aca1

| 611,261

|

Two positive rational numbers $x$ and $y$, when written in lowest terms, have the property that the sum of their numerators is 9 and the sum of their denominators is 10 . What is the largest possible value of $x+y$ ?

|

$73 / 9$

For fixed denominators $a<b$ (with sum 10), we maximize the sum of the fractions by giving the smaller denominator as large a numerator as possible: $8 / a+1 / b$. Then, if $a \geq 2$, this quantity is at most $8 / 2+1 / 1=5$, which is clearly smaller than the sum we get by setting $a=1$, namely $8 / 1+1 / 9=73 / 9$. So this is the answer.

|

\frac{73}{9}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Two positive rational numbers $x$ and $y$, when written in lowest terms, have the property that the sum of their numerators is 9 and the sum of their denominators is 10 . What is the largest possible value of $x+y$ ?

|

$73 / 9$

For fixed denominators $a<b$ (with sum 10), we maximize the sum of the fractions by giving the smaller denominator as large a numerator as possible: $8 / a+1 / b$. Then, if $a \geq 2$, this quantity is at most $8 / 2+1 / 1=5$, which is clearly smaller than the sum we get by setting $a=1$, namely $8 / 1+1 / 9=73 / 9$. So this is the answer.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n20. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

566b543d-1172-5d72-a7d9-049790da2c68

| 611,262

|

I have written a strictly increasing sequence of six positive integers, such that each number (besides the first) is a multiple of the one before it, and the sum of all six numbers is 79 . What is the largest number in my sequence?

|

48

If the fourth number is $\geq 12$, then the last three numbers must sum to at least $12+$ $2 \cdot 12+2^{2} \cdot 12=84>79$. This is impossible, so the fourth number must be less than 12. Then the only way we can have the required divisibilities among the first four numbers is if they are $1,2,4,8$. So the last two numbers now sum to $79-15=64$. If we call these numbers $8 a, 8 a b(a, b>1)$ then we get $a(1+b)=a+a b=8$, which forces $a=2, b=3$. So the last two numbers are 16,48 .

|

48

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

I have written a strictly increasing sequence of six positive integers, such that each number (besides the first) is a multiple of the one before it, and the sum of all six numbers is 79 . What is the largest number in my sequence?

|

48

If the fourth number is $\geq 12$, then the last three numbers must sum to at least $12+$ $2 \cdot 12+2^{2} \cdot 12=84>79$. This is impossible, so the fourth number must be less than 12. Then the only way we can have the required divisibilities among the first four numbers is if they are $1,2,4,8$. So the last two numbers now sum to $79-15=64$. If we call these numbers $8 a, 8 a b(a, b>1)$ then we get $a(1+b)=a+a b=8$, which forces $a=2, b=3$. So the last two numbers are 16,48 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n22. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

0ea623e4-8f94-5d02-822f-de40c8f6309f

| 611,264

|

Find the largest integer $n$ such that $3^{512}-1$ is divisible by $2^{n}$.

|

11

Write

$$

\begin{aligned}

3^{512}-1 & =\left(3^{256}+1\right)\left(3^{256}-1\right)=\left(3^{256}+1\right)\left(3^{128}+1\right)\left(3^{128}-1\right) \\

& =\cdots=\left(3^{256}+1\right)\left(3^{128}+1\right) \cdots(3+1)(3-1)

\end{aligned}

$$

Now each factor $3^{2^{k}}+1, k \geq 1$, is divisible by just one factor of 2 , since $3^{2^{k}}+1=$ $\left(3^{2}\right)^{2^{k-1}}+1 \equiv 1^{2^{k-1}}+1=2(\bmod 4)$. Thus we get 8 factors of 2 here, and the remaining terms $(3+1)(3-1)=8$ give us 3 more factors of 2 , for a total of 11 .

|

11

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find the largest integer $n$ such that $3^{512}-1$ is divisible by $2^{n}$.

|

11

Write

$$

\begin{aligned}

3^{512}-1 & =\left(3^{256}+1\right)\left(3^{256}-1\right)=\left(3^{256}+1\right)\left(3^{128}+1\right)\left(3^{128}-1\right) \\

& =\cdots=\left(3^{256}+1\right)\left(3^{128}+1\right) \cdots(3+1)(3-1)

\end{aligned}

$$

Now each factor $3^{2^{k}}+1, k \geq 1$, is divisible by just one factor of 2 , since $3^{2^{k}}+1=$ $\left(3^{2}\right)^{2^{k-1}}+1 \equiv 1^{2^{k-1}}+1=2(\bmod 4)$. Thus we get 8 factors of 2 here, and the remaining terms $(3+1)(3-1)=8$ give us 3 more factors of 2 , for a total of 11 .

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n23. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

e83bc1b1-3083-5a17-b96e-b69d0f5523cf

| 611,265

|

We say a point is contained in a square if it is in its interior or on its boundary. Three unit squares are given in the plane such that there is a point contained in all three. Furthermore, three points $A, B, C$, are given, each contained in at least one of the squares. Find the maximum area of triangle $A B C$.

|

$3 \sqrt{3} / 2$

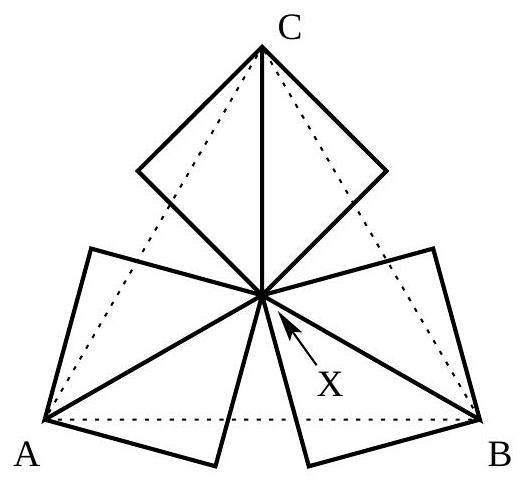

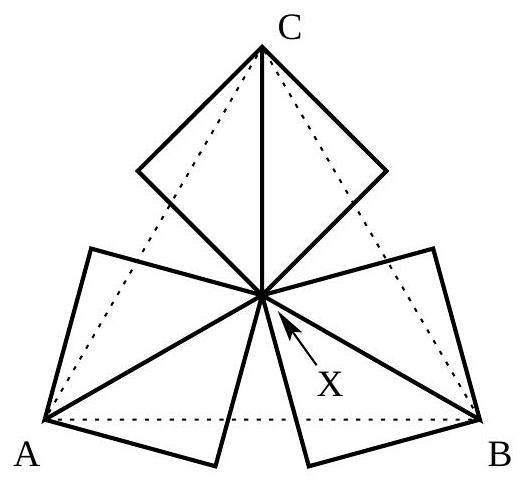

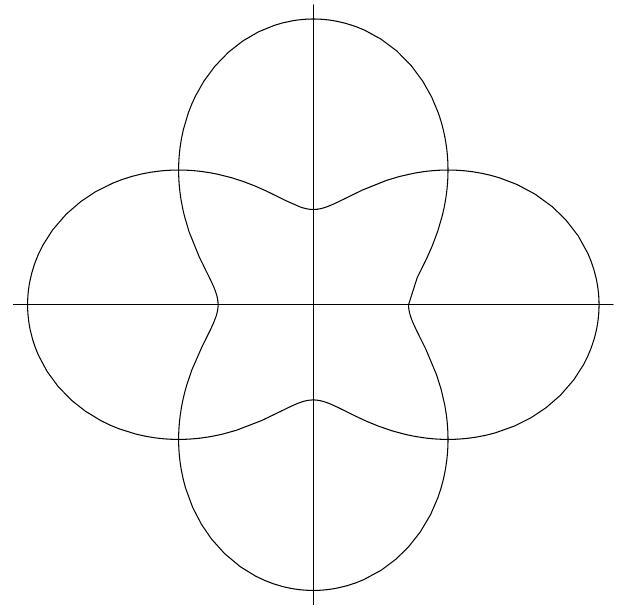

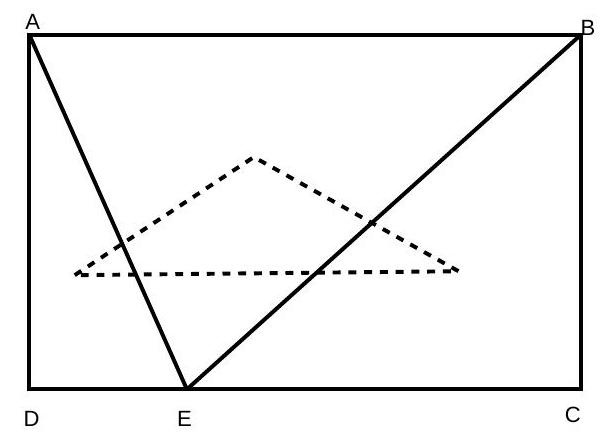

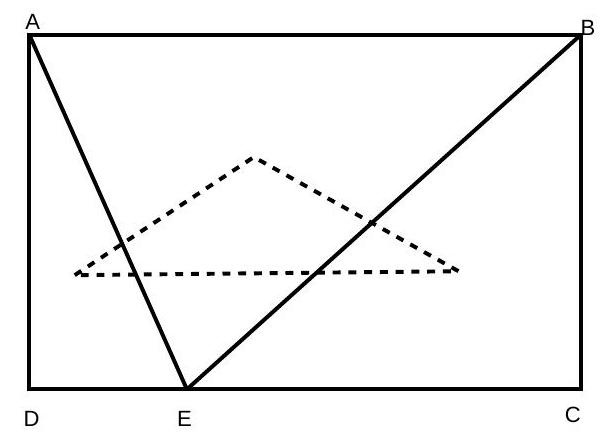

Let $X$ be a point contained in all three squares. The distance from $X$ to any point in any of the three squares is at most $\sqrt{2}$, the length of the diagonal of the squares. Therefore, triangle $A B C$ is contained in a circle of radius $\sqrt{2}$, so its circumradius is at most $\sqrt{2}$. The triangle with greatest area that satisfies this property is the equilateral triangle in a circle of radius $\sqrt{2}$. (This can be proved, for example, by considering that the maximum altitude to any given side is obtained by putting the opposite vertex at the midpoint of its arc, and it follows that all the vertices are equidistant.) The equilateral triangle is also attainable, since making $X$ the circumcenter and positioning the squares such that $A X, B X$, and $C X$ are diagonals (of the three squares) and $A B C$ is equilateral, leads to such a triangle. This triangle has area $3 \sqrt{3} / 2$, which may be calculated, for example, using the sine formula for area applied to $A B X, A C X$, and $B C X$, to get $3 / 2(\sqrt{2})^{2} \sin 120^{\circ}$. (See diagram, next page.)

|

\frac{3 \sqrt{3}}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

We say a point is contained in a square if it is in its interior or on its boundary. Three unit squares are given in the plane such that there is a point contained in all three. Furthermore, three points $A, B, C$, are given, each contained in at least one of the squares. Find the maximum area of triangle $A B C$.

|

$3 \sqrt{3} / 2$

Let $X$ be a point contained in all three squares. The distance from $X$ to any point in any of the three squares is at most $\sqrt{2}$, the length of the diagonal of the squares. Therefore, triangle $A B C$ is contained in a circle of radius $\sqrt{2}$, so its circumradius is at most $\sqrt{2}$. The triangle with greatest area that satisfies this property is the equilateral triangle in a circle of radius $\sqrt{2}$. (This can be proved, for example, by considering that the maximum altitude to any given side is obtained by putting the opposite vertex at the midpoint of its arc, and it follows that all the vertices are equidistant.) The equilateral triangle is also attainable, since making $X$ the circumcenter and positioning the squares such that $A X, B X$, and $C X$ are diagonals (of the three squares) and $A B C$ is equilateral, leads to such a triangle. This triangle has area $3 \sqrt{3} / 2$, which may be calculated, for example, using the sine formula for area applied to $A B X, A C X$, and $B C X$, to get $3 / 2(\sqrt{2})^{2} \sin 120^{\circ}$. (See diagram, next page.)

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n24. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

c097dfd9-2a98-54bb-8941-d332563717c7

| 611,266

|

Suppose $x^{3}-a x^{2}+b x-48$ is a polynomial with three positive roots $p, q$, and $r$ such that $p<q<r$. What is the minimum possible value of $1 / p+2 / q+3 / r$ ?

|

$3 / 2$

We know $p q r=48$ since the product of the roots of a cubic is the constant term. Now,

$$

\frac{1}{p}+\frac{2}{q}+\frac{3}{r} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{\frac{6}{p q r}}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

by AM-GM, with equality when $1 / p=2 / q=3 / r$. This occurs when $p=2, q=4$, $r=6$, so $3 / 2$ is in fact the minimum possible value.

|

\frac{3}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Suppose $x^{3}-a x^{2}+b x-48$ is a polynomial with three positive roots $p, q$, and $r$ such that $p<q<r$. What is the minimum possible value of $1 / p+2 / q+3 / r$ ?

|

$3 / 2$

We know $p q r=48$ since the product of the roots of a cubic is the constant term. Now,

$$

\frac{1}{p}+\frac{2}{q}+\frac{3}{r} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{\frac{6}{p q r}}=\frac{3}{2}

$$

by AM-GM, with equality when $1 / p=2 / q=3 / r$. This occurs when $p=2, q=4$, $r=6$, so $3 / 2$ is in fact the minimum possible value.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n25. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

7bfb79d1-a9a6-545c-b4c1-5c13061ea859

| 611,267

|

How many of the integers $1,2, \ldots, 2004$ can be represented as $(m n+1) /(m+n)$ for positive integers $m$ and $n$ ?

|

2004

For any positive integer $a$, we can let $m=a^{2}+a-1, n=a+1$ to see that every positive integer has this property, so the answer is 2004.

|

2004

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

How many of the integers $1,2, \ldots, 2004$ can be represented as $(m n+1) /(m+n)$ for positive integers $m$ and $n$ ?

|

2004

For any positive integer $a$, we can let $m=a^{2}+a-1, n=a+1$ to see that every positive integer has this property, so the answer is 2004.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n26. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

a243cec8-ac2d-554d-9d15-3e0f0fc879ec

| 611,268

|

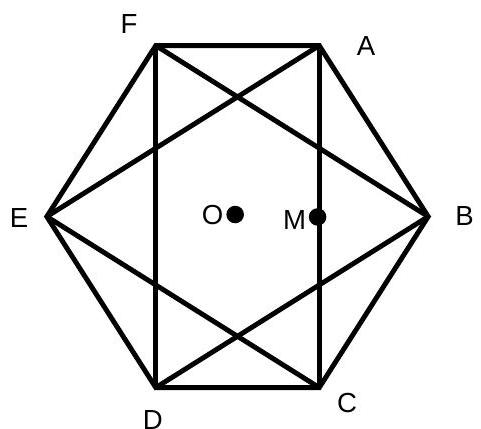

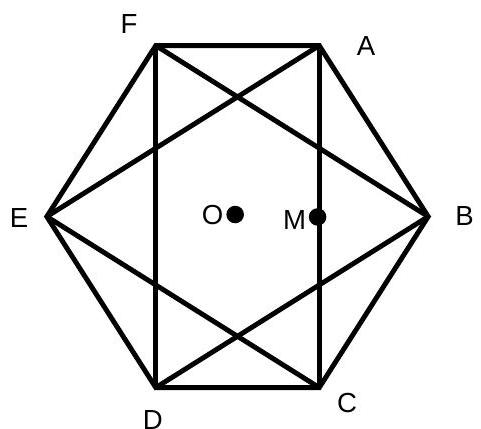

A regular hexagon has one side along the diameter of a semicircle, and the two opposite vertices on the semicircle. Find the area of the hexagon if the diameter of the semicircle is 1 .

|

$3 \sqrt{3} / 26$

The midpoint of the side of the hexagon on the diameter is the center of the circle. Draw the segment from this center to a vertex of the hexagon on the circle. This segment, whose length is $1 / 2$, is the hypotenuse of a right triangle whose legs have lengths $a / 2$ and $a \sqrt{3}$, where $a$ is a side of the hexagon. So $1 / 4=a^{2}(1 / 4+3)$, so $a^{2}=1 / 13$. The hexagon consists of 6 equilateral triangles of side length $a$, so the area of the hexagon is $3 a^{2} \sqrt{3} / 2=3 \sqrt{3} / 26$.

|

\frac{3 \sqrt{3}}{26}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A regular hexagon has one side along the diameter of a semicircle, and the two opposite vertices on the semicircle. Find the area of the hexagon if the diameter of the semicircle is 1 .

|

$3 \sqrt{3} / 26$

The midpoint of the side of the hexagon on the diameter is the center of the circle. Draw the segment from this center to a vertex of the hexagon on the circle. This segment, whose length is $1 / 2$, is the hypotenuse of a right triangle whose legs have lengths $a / 2$ and $a \sqrt{3}$, where $a$ is a side of the hexagon. So $1 / 4=a^{2}(1 / 4+3)$, so $a^{2}=1 / 13$. The hexagon consists of 6 equilateral triangles of side length $a$, so the area of the hexagon is $3 a^{2} \sqrt{3} / 2=3 \sqrt{3} / 26$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n27. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

aa32c862-9f59-59ce-b919-eacafdaee27c

| 611,269

|

Find the value of

$$

\binom{2003}{1}+\binom{2003}{4}+\binom{2003}{7}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2002}

$$

|

$\left(2^{2003}-2\right) / 3$

Let $\omega=-1 / 2+i \sqrt{3} / 2$ be a complex cube root of unity. Then, by the binomial theorem, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\omega^{2}(\omega+1)^{2003} & =\binom{2003}{0} \omega^{2}+\binom{2003}{1} \omega^{3}+\binom{2003}{2} \omega^{4}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2003} \omega^{2005} \\

2^{2003} & =\binom{2003}{0}+\binom{2003}{1}+\binom{2003}{2}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2003} \\

\omega^{-2}\left(\omega^{-1}+1\right)^{2003} & =\binom{2003}{0} \omega^{-2}+\binom{2003}{1} \omega^{-3}+\binom{2003}{2} \omega^{-4}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2003} \omega^{-2005}

\end{aligned}

$$

If we add these together, then the terms $\binom{2003}{n}$ for $n \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$ appear with coefficient 3 , while the remaining terms appear with coefficient $1+\omega+\omega^{2}=0$. Thus the desired sum is just $\left(\omega^{2}(\omega+1)^{2003}+2^{2003}+\omega^{-2}\left(\omega^{-1}+1\right)^{2003}\right) / 3$. Simplifying using $\omega+1=-\omega^{2}$ and $\omega^{-1}+1=-\omega$ gives $\left(-1+2^{2003}+-1\right) / 3=\left(2^{2003}-2\right) / 3$.

|

\frac{2^{2003}-2}{3}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Find the value of

$$

\binom{2003}{1}+\binom{2003}{4}+\binom{2003}{7}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2002}

$$

|

$\left(2^{2003}-2\right) / 3$

Let $\omega=-1 / 2+i \sqrt{3} / 2$ be a complex cube root of unity. Then, by the binomial theorem, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\omega^{2}(\omega+1)^{2003} & =\binom{2003}{0} \omega^{2}+\binom{2003}{1} \omega^{3}+\binom{2003}{2} \omega^{4}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2003} \omega^{2005} \\

2^{2003} & =\binom{2003}{0}+\binom{2003}{1}+\binom{2003}{2}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2003} \\

\omega^{-2}\left(\omega^{-1}+1\right)^{2003} & =\binom{2003}{0} \omega^{-2}+\binom{2003}{1} \omega^{-3}+\binom{2003}{2} \omega^{-4}+\cdots+\binom{2003}{2003} \omega^{-2005}

\end{aligned}

$$

If we add these together, then the terms $\binom{2003}{n}$ for $n \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$ appear with coefficient 3 , while the remaining terms appear with coefficient $1+\omega+\omega^{2}=0$. Thus the desired sum is just $\left(\omega^{2}(\omega+1)^{2003}+2^{2003}+\omega^{-2}\left(\omega^{-1}+1\right)^{2003}\right) / 3$. Simplifying using $\omega+1=-\omega^{2}$ and $\omega^{-1}+1=-\omega$ gives $\left(-1+2^{2003}+-1\right) / 3=\left(2^{2003}-2\right) / 3$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n28. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

d2207408-ea77-5a9d-9c8d-2446cb7f4c13

| 611,270

|

A regular dodecahedron is projected orthogonally onto a plane, and its image is an $n$-sided polygon. What is the smallest possible value of $n$ ?

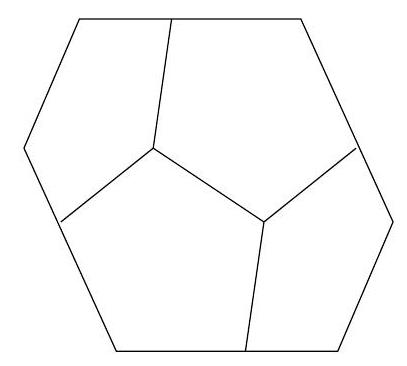

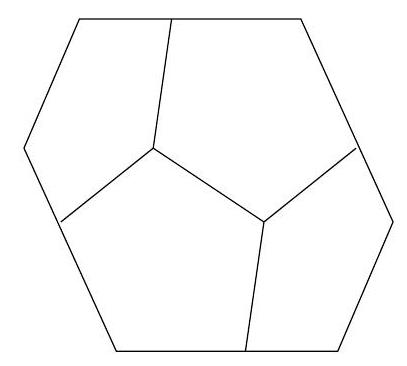

|

6

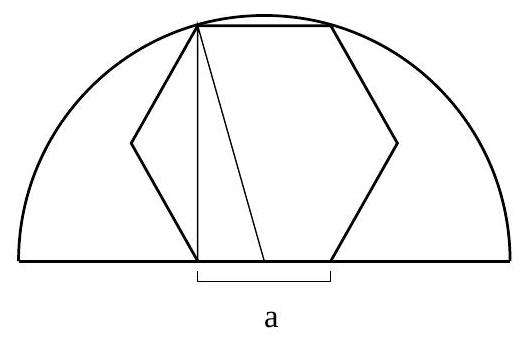

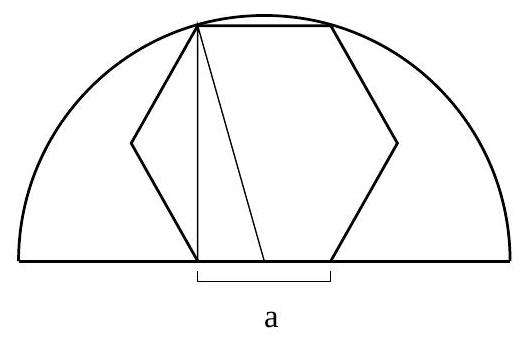

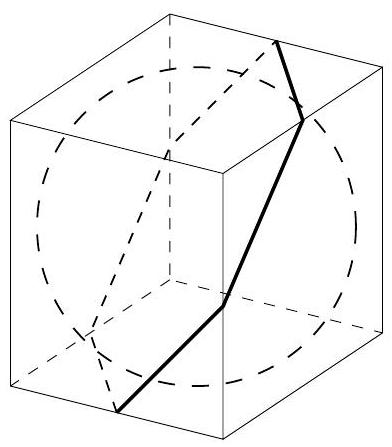

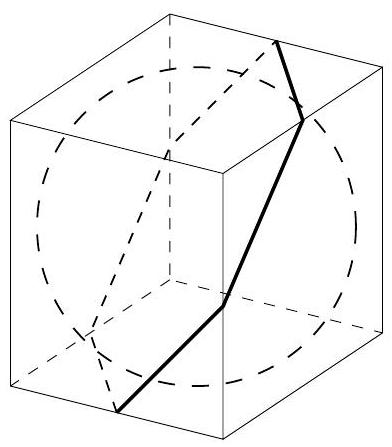

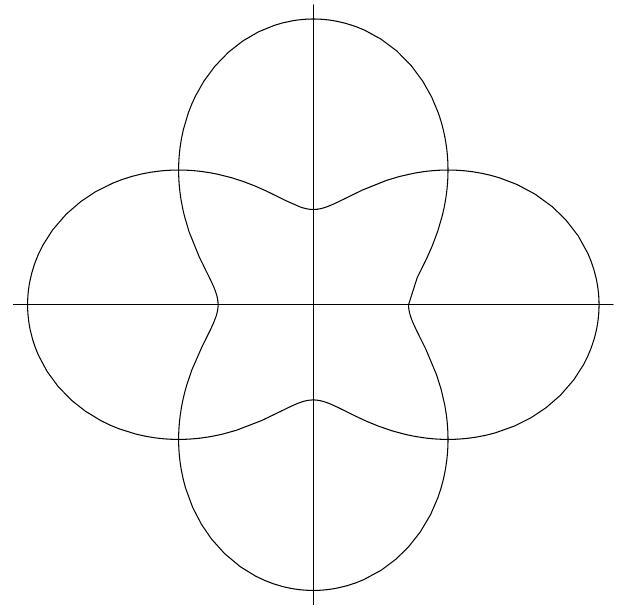

We can achieve 6 by projecting onto a plane perpendicular to an edge of the dodecaheron. Indeed, if we imagine viewing the dodecahedron in such a direction, then 4 of the faces are projected to line segments (namely, the two faces adjacent to the edge and the two opposite faces), and of the remaining 8 faces, 4 appear on the front of the dodecahedron and the other 4 are on the back. Thus, the dodecahedron appears as shown.

To see that we cannot do better, note that, by central symmetry, the number of edges of the projection must be even. So we just need to show that the answer cannot be 4 . But if the projection had 4 sides, one of the vertices would give a projection forming an acute angle, which is not possible. So 6 is the answer.

|

6

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A regular dodecahedron is projected orthogonally onto a plane, and its image is an $n$-sided polygon. What is the smallest possible value of $n$ ?

|

6

We can achieve 6 by projecting onto a plane perpendicular to an edge of the dodecaheron. Indeed, if we imagine viewing the dodecahedron in such a direction, then 4 of the faces are projected to line segments (namely, the two faces adjacent to the edge and the two opposite faces), and of the remaining 8 faces, 4 appear on the front of the dodecahedron and the other 4 are on the back. Thus, the dodecahedron appears as shown.

To see that we cannot do better, note that, by central symmetry, the number of edges of the projection must be even. So we just need to show that the answer cannot be 4 . But if the projection had 4 sides, one of the vertices would give a projection forming an acute angle, which is not possible. So 6 is the answer.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n29. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

a0fc03a1-8ba2-56ee-aab1-885bc153062d

| 611,271

|

We have an $n$-gon, and each of its vertices is labeled with a number from the set $\{1, \ldots, 10\}$. We know that for any pair of distinct numbers from this set there is

at least one side of the polygon whose endpoints have these two numbers. Find the smallest possible value of $n$.

|

Each number be paired with each of the 9 other numbers, but each vertex can be used in at most 2 different pairs, so each number must occur on at least $\lceil 9 / 2\rceil=5$ different vertices. Thus, we need at least $10 \cdot 5=50$ vertices, so $n \geq 50$.

To see that $n=50$ is feasible, let the numbers $1, \ldots, 10$ be the vertices of a complete graph. Then each vertex has degree 9 , and there are $\binom{10}{2}=45$ edges. If we attach extra copies of the edges $1-2,3-4,5-6,7-8$, and $9-10$, then every vertex will have degree 10 . In particular, the graph has an Eulerian tour, so we can follow this tour, successively numbering vertices of the 50 -gon according to the vertices of the graph we visit. Then, for each edge of the graph, there will be a corresponding edge of the polygon with the same two vertex labels on its endpoints. It follows that every pair of distinct numbers occurs at the endpoints of some edge of the polygon, and so $n=50$ is the answer.

|

50

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

We have an $n$-gon, and each of its vertices is labeled with a number from the set $\{1, \ldots, 10\}$. We know that for any pair of distinct numbers from this set there is

at least one side of the polygon whose endpoints have these two numbers. Find the smallest possible value of $n$.

|

Each number be paired with each of the 9 other numbers, but each vertex can be used in at most 2 different pairs, so each number must occur on at least $\lceil 9 / 2\rceil=5$ different vertices. Thus, we need at least $10 \cdot 5=50$ vertices, so $n \geq 50$.

To see that $n=50$ is feasible, let the numbers $1, \ldots, 10$ be the vertices of a complete graph. Then each vertex has degree 9 , and there are $\binom{10}{2}=45$ edges. If we attach extra copies of the edges $1-2,3-4,5-6,7-8$, and $9-10$, then every vertex will have degree 10 . In particular, the graph has an Eulerian tour, so we can follow this tour, successively numbering vertices of the 50 -gon according to the vertices of the graph we visit. Then, for each edge of the graph, there will be a corresponding edge of the polygon with the same two vertex labels on its endpoints. It follows that every pair of distinct numbers occurs at the endpoints of some edge of the polygon, and so $n=50$ is the answer.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n30. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:\n"

}

|

61428846-4fda-5fa9-9efa-99dd50bd1469

| 611,272

|

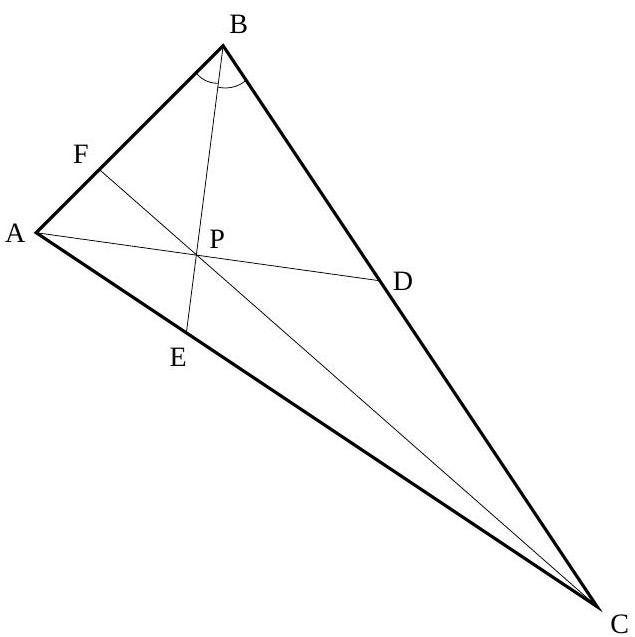

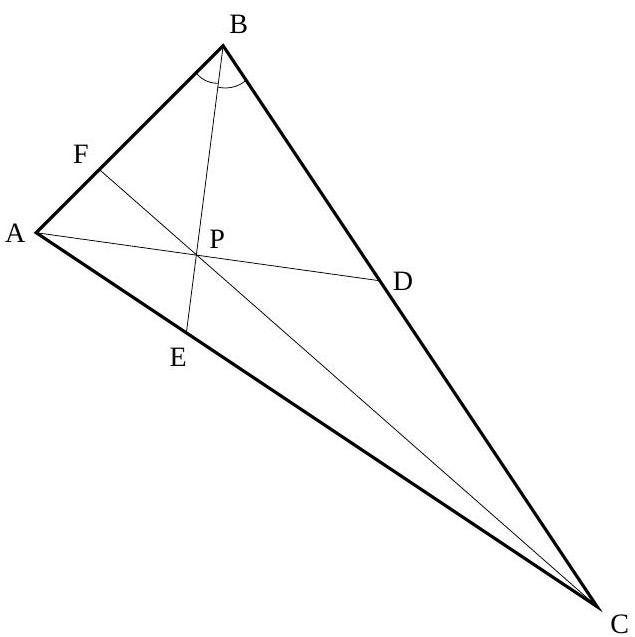

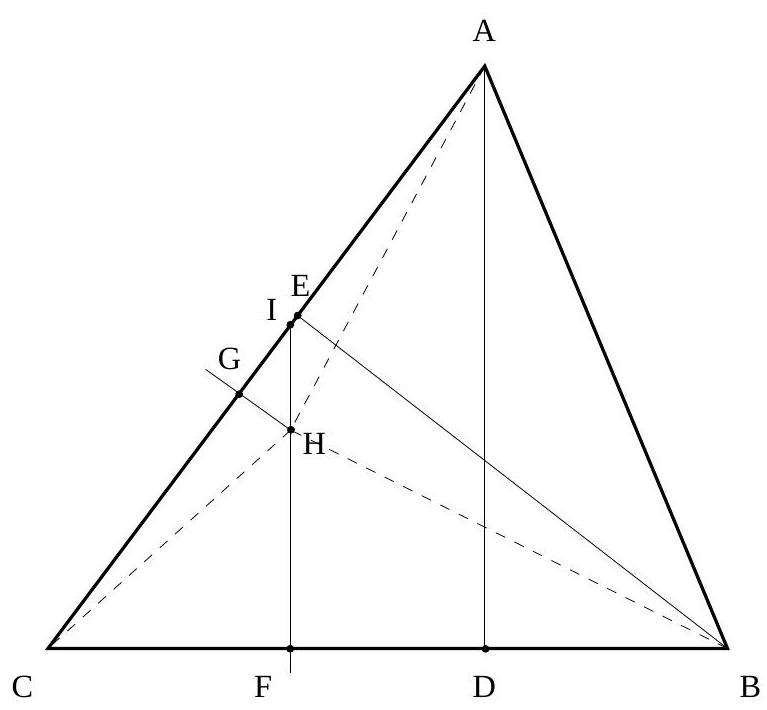

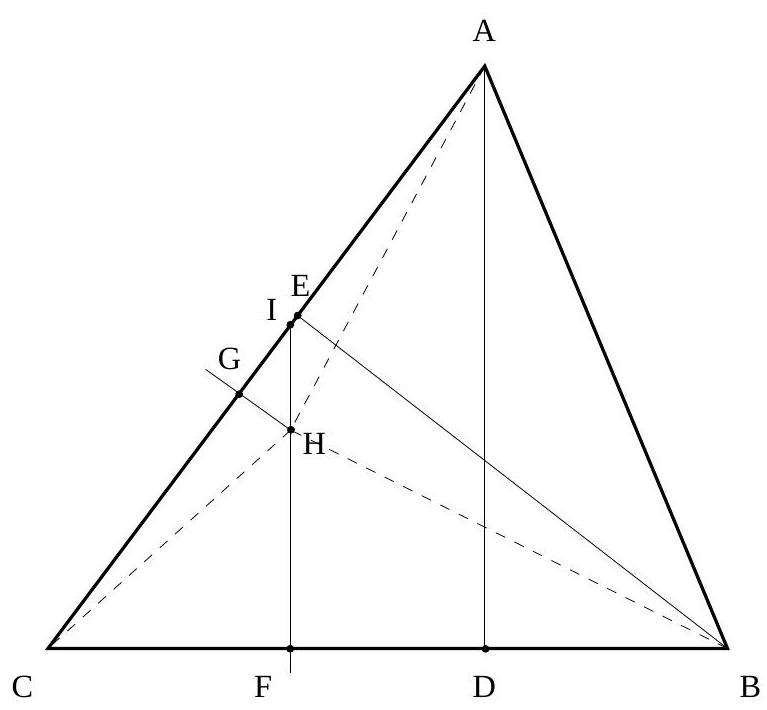

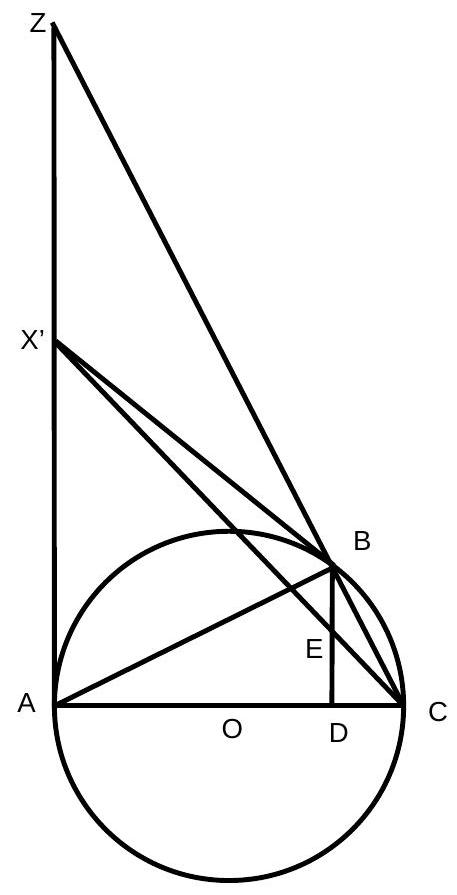

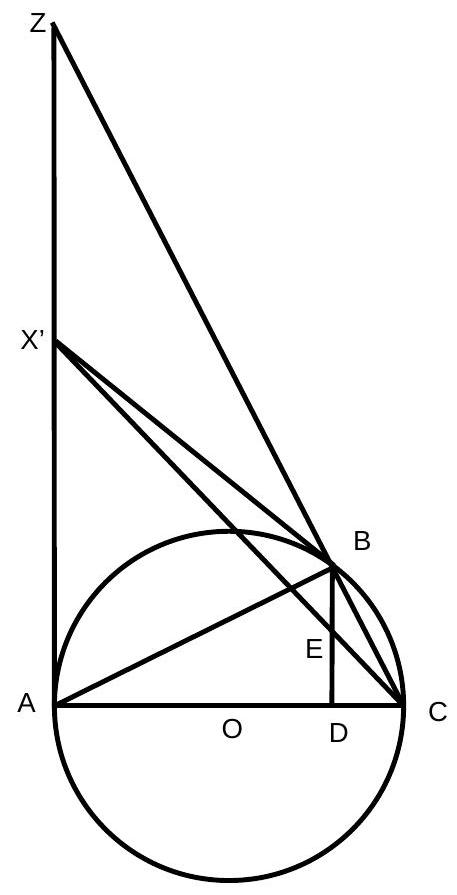

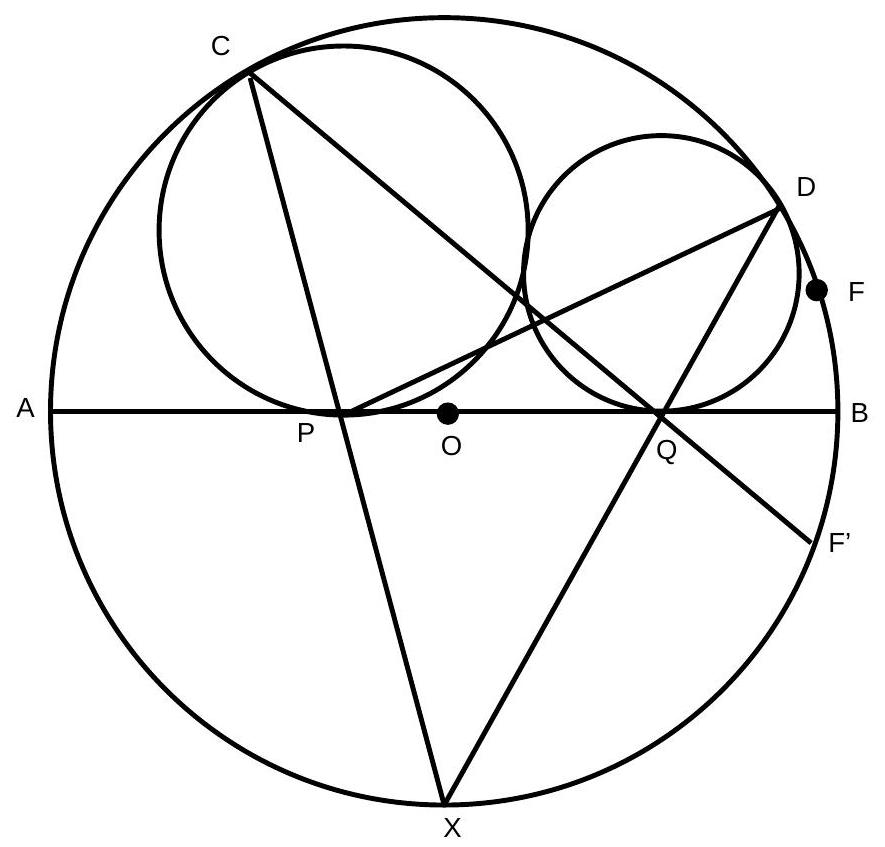

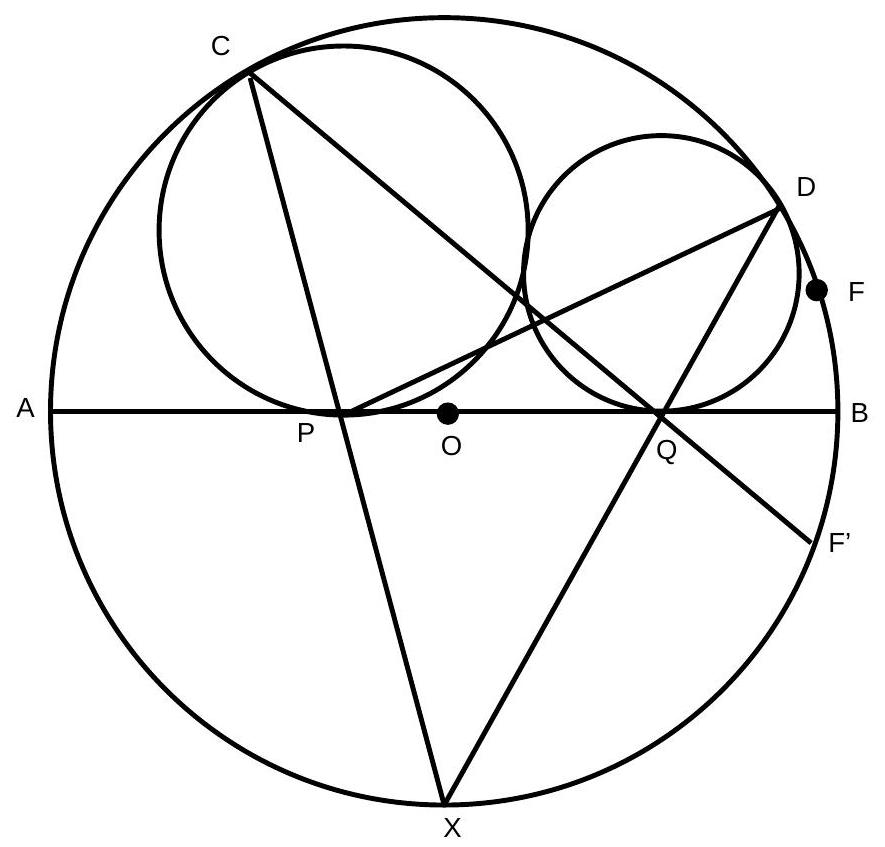

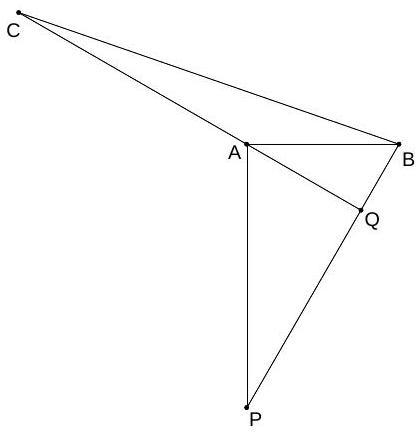

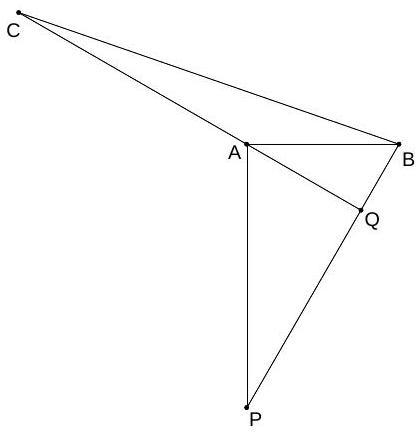

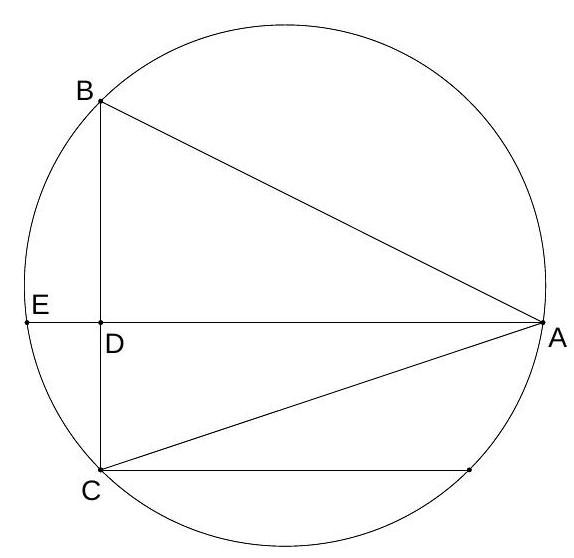

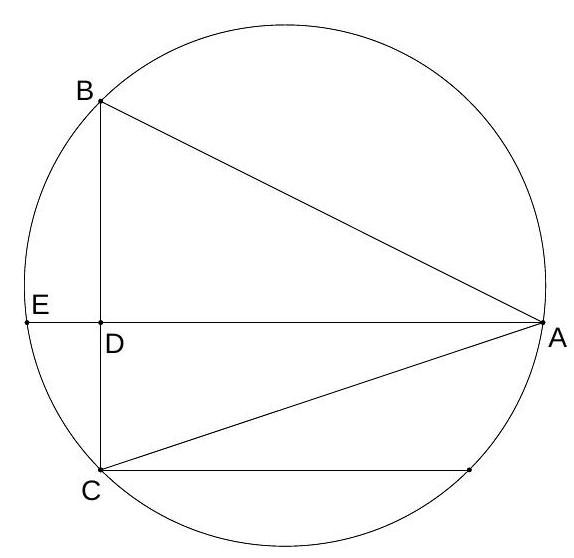

$P$ is a point inside triangle $A B C$, and lines $A P, B P, C P$ intersect the opposite sides $B C, C A, A B$ in points $D, E, F$, respectively. It is given that $\angle A P B=90^{\circ}$, and that $A C=B C$ and $A B=B D$. We also know that $B F=1$, and that $B C=999$. Find $A F$.

|

499/500

Let $A C=B C=s, A B=B D=t$. Since $B P$ is the altitude in isosceles triangle $A B D$, it bisects angle $B$. So, the Angle Bisector Theorem in triangle $A B C$ given $A E / E C=A B / B C=t / s$. Meanwhile, $C D / D B=(s-t) / t$. Now Ceva's theorem gives us

$$

\begin{gathered}

\frac{A F}{F B}=\left(\frac{A E}{E C}\right) \cdot\left(\frac{C D}{D B}\right)=\frac{s-t}{s} \\

\Rightarrow \frac{A B}{F B}=1+\frac{s-t}{s}=\frac{2 s-t}{s} \Rightarrow F B=\frac{s t}{2 s-t} .

\end{gathered}

$$

Now we know $s=999$, but we need to find $t$ given that $s t /(2 s-t)=F B=1$. So $s t=2 s-t \Rightarrow t=2 s /(s+1)$, and then

$$

A F=F B \cdot \frac{A F}{F B}=1 \cdot \frac{s-t}{s}=\frac{\left(s^{2}-s\right) /(s+1)}{s}=\frac{s-1}{s+1}=\frac{499}{500} .

$$

|

\frac{499}{500}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

$P$ is a point inside triangle $A B C$, and lines $A P, B P, C P$ intersect the opposite sides $B C, C A, A B$ in points $D, E, F$, respectively. It is given that $\angle A P B=90^{\circ}$, and that $A C=B C$ and $A B=B D$. We also know that $B F=1$, and that $B C=999$. Find $A F$.

|

499/500

Let $A C=B C=s, A B=B D=t$. Since $B P$ is the altitude in isosceles triangle $A B D$, it bisects angle $B$. So, the Angle Bisector Theorem in triangle $A B C$ given $A E / E C=A B / B C=t / s$. Meanwhile, $C D / D B=(s-t) / t$. Now Ceva's theorem gives us

$$

\begin{gathered}

\frac{A F}{F B}=\left(\frac{A E}{E C}\right) \cdot\left(\frac{C D}{D B}\right)=\frac{s-t}{s} \\

\Rightarrow \frac{A B}{F B}=1+\frac{s-t}{s}=\frac{2 s-t}{s} \Rightarrow F B=\frac{s t}{2 s-t} .

\end{gathered}

$$

Now we know $s=999$, but we need to find $t$ given that $s t /(2 s-t)=F B=1$. So $s t=2 s-t \Rightarrow t=2 s /(s+1)$, and then

$$

A F=F B \cdot \frac{A F}{F B}=1 \cdot \frac{s-t}{s}=\frac{\left(s^{2}-s\right) /(s+1)}{s}=\frac{s-1}{s+1}=\frac{499}{500} .

$$

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n31. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

327cb972-d44f-515a-9fe8-3bcb0552677b

| 611,273

|

A plane $P$ slices through a cube of volume 1 with a cross-section in the shape of a regular hexagon. This cube also has an inscribed sphere, whose intersection with $P$ is a circle. What is the area of the region inside the regular hexagon but outside the circle?

|

$\quad(3 \sqrt{3}-\pi) / 4$

One can show that the hexagon must have as its vertices the midpoints of six edges of the cube, as illustrated; for example, this readily follows from the fact that opposite sides of the hexagons and the medians between them are parallel. We then conclude that the side of the hexagon is $\sqrt{2} / 2$ (since it cuts off an isosceles triangle of leg $1 / 2$ from each face), so the area is $(3 / 2)(\sqrt{2} / 2)^{2}(\sqrt{3})=3 \sqrt{3} / 4$. Also, the plane passes through the center of the sphere by symmetry, so it cuts out a cross section of radius $1 / 2$, whose area (which is contained entirely inside the hexagon) is then $\pi / 4$. The sought area is thus $(3 \sqrt{3}-\pi) / 4$.

|

(3 \sqrt{3}-\pi) / 4

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A plane $P$ slices through a cube of volume 1 with a cross-section in the shape of a regular hexagon. This cube also has an inscribed sphere, whose intersection with $P$ is a circle. What is the area of the region inside the regular hexagon but outside the circle?

|

$\quad(3 \sqrt{3}-\pi) / 4$

One can show that the hexagon must have as its vertices the midpoints of six edges of the cube, as illustrated; for example, this readily follows from the fact that opposite sides of the hexagons and the medians between them are parallel. We then conclude that the side of the hexagon is $\sqrt{2} / 2$ (since it cuts off an isosceles triangle of leg $1 / 2$ from each face), so the area is $(3 / 2)(\sqrt{2} / 2)^{2}(\sqrt{3})=3 \sqrt{3} / 4$. Also, the plane passes through the center of the sphere by symmetry, so it cuts out a cross section of radius $1 / 2$, whose area (which is contained entirely inside the hexagon) is then $\pi / 4$. The sought area is thus $(3 \sqrt{3}-\pi) / 4$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n33. ",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution: "

}

|

a4a70167-8ebb-5c1a-aa94-9d649e1e2a9f

| 611,275

|

There are eleven positive integers $n$ such that there exists a convex polygon with $n$ sides whose angles, in degrees, are unequal integers that are in arithmetic progression. Find the sum of these values of $n$.

|

106

The sum of the angles of an $n$-gon is $(n-2) 180$, so the average angle measure is $(n-2) 180 / n$. The common difference in this arithmetic progression is at least 1 , so the difference between the largest and smallest angles is at least $n-1$. So the largest angle is at least $(n-1) / 2+(n-2) 180 / n$. Since the polygon is convex, this quantity is no larger than 179: $(n-1) / 2-360 / n \leq-1$, so that $360 / n-n / 2 \geq 1 / 2$. Multiplying by $2 n$ gives $720-n^{2} \geq n$. So $n(n+1) \leq 720$, which forces $n \leq 26$. Of course, since the common difference is an integer, and the angle measures are integers, $(n-2) 180 / n$ must be an integer or a half integer, so $(n-2) 360 / n=360-720 / n$ is an integer, and then $720 / n$ must be an integer. This leaves only $n=3,4,5,6,8,9,10,12,15,16,18,20,24$ as possibilities. When $n$ is even, $(n-2) 180 / n$ is not an angle of the polygon, but the mean of the two middle angles. So the common difference is at least 2 when $(n-2) 180 / n$ is an integer. For $n=20$, the middle angle is 162 , so the largest angle is at least $162+38 / 2=181$, since 38 is no larger than the difference between the smallest and largest angles. For $n=24$, the middle angle is 165 , again leading to a contradiction. So no solution exists for $n=20,24$. All of the others possess solutions:

| $n$ | angles |

| :---: | :--- |

| 3 | $59,60,61$ |

| 4 | $87,89,91,93$ |

| 5 | $106,107,108,109,110$ |

| 6 | $115,117,119,121,123,125$ |

| 8 | $128,130,132,134,136,138,140,142$ |

| 9 | $136, \ldots, 144$ |

| 10 | $135,137,139, \ldots, 153$ |

| 12 | $139,141,143, \ldots, 161$ |

| 15 | $149,150, \ldots, 163$ |

| 16 | $150,151, \ldots, 165$ |

| 18 | $143,145, \ldots, 177$ |

(These solutions are quite easy to construct.) The desired value is then $3+4+5+6+$ $8+9+10+12+15+16+18=106$.

|

106

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

There are eleven positive integers $n$ such that there exists a convex polygon with $n$ sides whose angles, in degrees, are unequal integers that are in arithmetic progression. Find the sum of these values of $n$.

|

106

The sum of the angles of an $n$-gon is $(n-2) 180$, so the average angle measure is $(n-2) 180 / n$. The common difference in this arithmetic progression is at least 1 , so the difference between the largest and smallest angles is at least $n-1$. So the largest angle is at least $(n-1) / 2+(n-2) 180 / n$. Since the polygon is convex, this quantity is no larger than 179: $(n-1) / 2-360 / n \leq-1$, so that $360 / n-n / 2 \geq 1 / 2$. Multiplying by $2 n$ gives $720-n^{2} \geq n$. So $n(n+1) \leq 720$, which forces $n \leq 26$. Of course, since the common difference is an integer, and the angle measures are integers, $(n-2) 180 / n$ must be an integer or a half integer, so $(n-2) 360 / n=360-720 / n$ is an integer, and then $720 / n$ must be an integer. This leaves only $n=3,4,5,6,8,9,10,12,15,16,18,20,24$ as possibilities. When $n$ is even, $(n-2) 180 / n$ is not an angle of the polygon, but the mean of the two middle angles. So the common difference is at least 2 when $(n-2) 180 / n$ is an integer. For $n=20$, the middle angle is 162 , so the largest angle is at least $162+38 / 2=181$, since 38 is no larger than the difference between the smallest and largest angles. For $n=24$, the middle angle is 165 , again leading to a contradiction. So no solution exists for $n=20,24$. All of the others possess solutions:

| $n$ | angles |

| :---: | :--- |

| 3 | $59,60,61$ |

| 4 | $87,89,91,93$ |

| 5 | $106,107,108,109,110$ |

| 6 | $115,117,119,121,123,125$ |

| 8 | $128,130,132,134,136,138,140,142$ |

| 9 | $136, \ldots, 144$ |

| 10 | $135,137,139, \ldots, 153$ |

| 12 | $139,141,143, \ldots, 161$ |

| 15 | $149,150, \ldots, 163$ |

| 16 | $150,151, \ldots, 165$ |

| 18 | $143,145, \ldots, 177$ |

(These solutions are quite easy to construct.) The desired value is then $3+4+5+6+$ $8+9+10+12+15+16+18=106$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n35. ",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution: "

}

|

0bb45d7b-afbd-5380-a50f-f3a2b93da2d6

| 611,277

|

For a string of $P$ 's and $Q$ 's, the value is defined to be the product of the positions of the $P$ 's. For example, the string $P P Q P Q Q$ has value $1 \cdot 2 \cdot 4=8$.

Also, a string is called antipalindromic if writing it backwards, then turning all the $P$ 's into $Q$ 's and vice versa, produces the original string. For example, $P P Q P Q Q$ is antipalindromic.

There are $2^{1002}$ antipalindromic strings of length 2004. Find the sum of the reciprocals of their values.

|

$2005^{1002} / 2004$ !

Consider the product

$$

\left(\frac{1}{1}+\frac{1}{2004}\right)\left(\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2003}\right)\left(\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{2002}\right) \cdots\left(\frac{1}{1002}+\frac{1}{1003}\right) .

$$

This product expands to $2^{1002}$ terms, and each term gives the reciprocal of the value of a corresponding antipalindromic string of $P$ 's and $Q$ 's as follows: if we choose the term $1 / n$ for the $n$th factor, then our string has a $P$ in position $n$ and $Q$ in position $2005-n$; if we choose the term $1 /(2005-n)$, then we get a $Q$ in position $n$ and $P$ in position $2005-n$. Conversely, each antipalindromic string has its value represented by exactly one of our $2^{1002}$ terms. So the value of the product is the number we are looking for. But when we simplify this product, the $n$th factor becomes $1 / n+1 /(2005-n)=2005 / n(2005-n)$. Multiplying these together, we get 1002 factors of 2005 in the numerator and each integer from 1 to 2004 exactly once in the denominator, for a total of $2005^{1002}$ /2004!.

|

\frac{2005^{1002}}{2004!}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

For a string of $P$ 's and $Q$ 's, the value is defined to be the product of the positions of the $P$ 's. For example, the string $P P Q P Q Q$ has value $1 \cdot 2 \cdot 4=8$.

Also, a string is called antipalindromic if writing it backwards, then turning all the $P$ 's into $Q$ 's and vice versa, produces the original string. For example, $P P Q P Q Q$ is antipalindromic.

There are $2^{1002}$ antipalindromic strings of length 2004. Find the sum of the reciprocals of their values.

|

$2005^{1002} / 2004$ !

Consider the product

$$

\left(\frac{1}{1}+\frac{1}{2004}\right)\left(\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2003}\right)\left(\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{2002}\right) \cdots\left(\frac{1}{1002}+\frac{1}{1003}\right) .

$$

This product expands to $2^{1002}$ terms, and each term gives the reciprocal of the value of a corresponding antipalindromic string of $P$ 's and $Q$ 's as follows: if we choose the term $1 / n$ for the $n$th factor, then our string has a $P$ in position $n$ and $Q$ in position $2005-n$; if we choose the term $1 /(2005-n)$, then we get a $Q$ in position $n$ and $P$ in position $2005-n$. Conversely, each antipalindromic string has its value represented by exactly one of our $2^{1002}$ terms. So the value of the product is the number we are looking for. But when we simplify this product, the $n$th factor becomes $1 / n+1 /(2005-n)=2005 / n(2005-n)$. Multiplying these together, we get 1002 factors of 2005 in the numerator and each integer from 1 to 2004 exactly once in the denominator, for a total of $2005^{1002}$ /2004!.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n36. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

77fe7ad9-9307-5f92-bc74-0f882f4060b0

| 611,278

|

Simplify $\prod_{k=1}^{2004} \sin (2 \pi k / 4009)$.

|

## $\frac{\sqrt{4009}}{2^{2004}}$

Let $\zeta=e^{2 \pi i / 4009}$ so that $\sin (2 \pi k / 4009)=\frac{\zeta^{k}-\zeta^{-k}}{2 i}$ and $x^{4009}-1=\prod_{k=0}^{4008}\left(x-\zeta^{k}\right)$. Hence $1+x+\cdots+x^{4008}=\prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(x-\zeta^{k}\right)$. Comparing constant coefficients gives $\prod_{k=1}^{4008} \zeta^{k}=1$, setting $x=1$ gives $\prod_{k=1}^{40 \overline{0} \overline{8}}\left(1-\zeta^{k}\right)=4009$, and setting $x=-1$ gives $\prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(1+\zeta^{k}\right)=1$. Now, note that $\sin (2 \pi(4009-k) / 4009)=-\sin (2 \pi k / 4009)$, so

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\prod_{k=1}^{2004} \sin (2 \pi k / 4009)\right)^{2} & =(-1)^{2004} \prod_{k=1}^{4008} \sin (2 \pi k / 4009) \\

& =\prod_{k=1}^{4008} \frac{\zeta^{k}-\zeta^{-k}}{2 i} \\

& =\frac{1}{(2 i)^{4008}} \prod_{k=1}^{4008} \frac{\zeta^{2 k}-1}{\zeta^{k}} \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{4008}} \prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(\zeta^{2 k}-1\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{4008}} \prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(\zeta^{k}-1\right)\left(\zeta^{k}+1\right) \\

& =\frac{4009 \cdot 1}{2^{4008}} .

\end{aligned}

$$

However, $\sin (x)$ is nonnegative on the interval $[0, \pi]$, so our product is positive. Hence it is $\frac{\sqrt{4009}}{2^{2004}}$.

|

\frac{\sqrt{4009}}{2^{2004}}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Simplify $\prod_{k=1}^{2004} \sin (2 \pi k / 4009)$.

|

## $\frac{\sqrt{4009}}{2^{2004}}$

Let $\zeta=e^{2 \pi i / 4009}$ so that $\sin (2 \pi k / 4009)=\frac{\zeta^{k}-\zeta^{-k}}{2 i}$ and $x^{4009}-1=\prod_{k=0}^{4008}\left(x-\zeta^{k}\right)$. Hence $1+x+\cdots+x^{4008}=\prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(x-\zeta^{k}\right)$. Comparing constant coefficients gives $\prod_{k=1}^{4008} \zeta^{k}=1$, setting $x=1$ gives $\prod_{k=1}^{40 \overline{0} \overline{8}}\left(1-\zeta^{k}\right)=4009$, and setting $x=-1$ gives $\prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(1+\zeta^{k}\right)=1$. Now, note that $\sin (2 \pi(4009-k) / 4009)=-\sin (2 \pi k / 4009)$, so

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\prod_{k=1}^{2004} \sin (2 \pi k / 4009)\right)^{2} & =(-1)^{2004} \prod_{k=1}^{4008} \sin (2 \pi k / 4009) \\

& =\prod_{k=1}^{4008} \frac{\zeta^{k}-\zeta^{-k}}{2 i} \\

& =\frac{1}{(2 i)^{4008}} \prod_{k=1}^{4008} \frac{\zeta^{2 k}-1}{\zeta^{k}} \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{4008}} \prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(\zeta^{2 k}-1\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{4008}} \prod_{k=1}^{4008}\left(\zeta^{k}-1\right)\left(\zeta^{k}+1\right) \\

& =\frac{4009 \cdot 1}{2^{4008}} .

\end{aligned}

$$

However, $\sin (x)$ is nonnegative on the interval $[0, \pi]$, so our product is positive. Hence it is $\frac{\sqrt{4009}}{2^{2004}}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n37. ",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution:\n\n"

}

|

c881a637-6dc9-5989-b1f0-b76a00fb9842

| 611,279

|

Let $S=\left\{p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{n} \mid p_{1}, p_{2}, \ldots, p_{n}\right.$ are distinct primes and $\left.p_{1}, \ldots, p_{n}<30\right\}$. Assume 1 is in $S$. Let $a_{1}$ be an element of $S$. We define, for all positive integers $n$ :

$$

\begin{gathered}

a_{n+1}=a_{n} /(n+1) \quad \text { if } a_{n} \text { is divisible by } n+1 \\

a_{n+1}=(n+2) a_{n} \\

\text { if } a_{n} \text { is not divisible by } n+1

\end{gathered}

$$

How many distinct possible values of $a_{1}$ are there such that $a_{j}=a_{1}$ for infinitely many $j$ 's?

|

512

If $a_{1}$ is odd, then we can see by induction that $a_{j}=(j+1) a_{1}$ when $j$ is even and $a_{j}=a_{1}$ when $j$ is odd (using the fact that no even $j$ can divide $a_{1}$ ). So we have infinitely many $j$ 's for which $a_{j}=a_{1}$.

If $a_{1}>2$ is even, then $a_{2}$ is odd, since $a_{2}=a_{1} / 2$, and $a_{1}$ may have only one factor of 2. Now, in general, let $p=\min \left(\left\{p_{1}, \ldots, p_{n}\right\} \backslash\{2\}\right)$. Suppose $1<j<p$. By induction, we have $a_{j}=(j+1) a_{1} / 2$ when $j$ is odd, and $a_{j}=a_{1} / 2$ when $j$ is even. So $a_{i} \neq a_{1}$ for all $1<j<p$. It follows that $a_{p}=a_{1} / 2 p$. Then, again using induction, we get for all nonnegative integers $k$ that $a_{p+k}=a_{p}$ if $k$ is even, and $a_{p+k}=(p+k+1) a_{p}$ if $k$ is odd. Clearly, $a_{p} \neq a_{1}$ and $p+k+1 \neq 2 p$ when $k$ is odd (the left side is odd, and the right side even). It follows that $a_{j}=a_{1}$ for no $j>1$. Finally, when $a_{1}=2$, we can check inductively that $a_{j}=j+1$ for $j$ odd and $a_{j}=1$ for $j$ even.

So our answer is just the number of odd elements in $S$. There are 9 odd prime numbers smaller than 30 , so the answer is $2^{9}=512$.

|

512

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $S=\left\{p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{n} \mid p_{1}, p_{2}, \ldots, p_{n}\right.$ are distinct primes and $\left.p_{1}, \ldots, p_{n}<30\right\}$. Assume 1 is in $S$. Let $a_{1}$ be an element of $S$. We define, for all positive integers $n$ :

$$

\begin{gathered}

a_{n+1}=a_{n} /(n+1) \quad \text { if } a_{n} \text { is divisible by } n+1 \\

a_{n+1}=(n+2) a_{n} \\

\text { if } a_{n} \text { is not divisible by } n+1

\end{gathered}

$$

How many distinct possible values of $a_{1}$ are there such that $a_{j}=a_{1}$ for infinitely many $j$ 's?

|

512

If $a_{1}$ is odd, then we can see by induction that $a_{j}=(j+1) a_{1}$ when $j$ is even and $a_{j}=a_{1}$ when $j$ is odd (using the fact that no even $j$ can divide $a_{1}$ ). So we have infinitely many $j$ 's for which $a_{j}=a_{1}$.

If $a_{1}>2$ is even, then $a_{2}$ is odd, since $a_{2}=a_{1} / 2$, and $a_{1}$ may have only one factor of 2. Now, in general, let $p=\min \left(\left\{p_{1}, \ldots, p_{n}\right\} \backslash\{2\}\right)$. Suppose $1<j<p$. By induction, we have $a_{j}=(j+1) a_{1} / 2$ when $j$ is odd, and $a_{j}=a_{1} / 2$ when $j$ is even. So $a_{i} \neq a_{1}$ for all $1<j<p$. It follows that $a_{p}=a_{1} / 2 p$. Then, again using induction, we get for all nonnegative integers $k$ that $a_{p+k}=a_{p}$ if $k$ is even, and $a_{p+k}=(p+k+1) a_{p}$ if $k$ is odd. Clearly, $a_{p} \neq a_{1}$ and $p+k+1 \neq 2 p$ when $k$ is odd (the left side is odd, and the right side even). It follows that $a_{j}=a_{1}$ for no $j>1$. Finally, when $a_{1}=2$, we can check inductively that $a_{j}=j+1$ for $j$ odd and $a_{j}=1$ for $j$ even.

So our answer is just the number of odd elements in $S$. There are 9 odd prime numbers smaller than 30 , so the answer is $2^{9}=512$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n38. ",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution: "

}

|

551c71ab-3e70-5913-91ed-2d1ff98cb782

| 611,280

|

You want to arrange the numbers $1,2,3, \ldots, 25$ in a sequence with the following property: if $n$ is divisible by $m$, then the $n$th number is divisible by the $m$ th number. How many such sequences are there?

|

24

Let the rearranged numbers be $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{25}$. The number of pairs $(n, m)$ with $n \mid m$ must equal the number of pairs with $a_{n} \mid a_{m}$, but since each pair of the former type is also of the latter type, the converse must be true as well. Thus, $n \mid m$ if and only if $a_{n} \mid a_{m}$. Now for each $n=1,2, \ldots, 6$, the number of values divisible by $n$ uniquely determines $n$, so $n=a_{n}$. Similarly, 7, 8 must either be kept fixed by the rearrangement or interchanged, because they are the only values that divide exactly 2 other numbers in the sequence; since 7 is prime and 8 is not, we conclude they are kept fixed. Then we can easily check by induction that $n=a_{n}$ for all larger composite numbers $n \leq 25$ (by using $m=a_{m}$ for all proper factors $m$ of $n$ ) and $n=11$ (because it is the only prime that divides exactly 1 other number). So we have only the primes $n=13,17,19,23$ left to rearrange, and it is easily seen that these can be permuted arbitrarily, leaving 4 ! possible orderings altogether.

|

24

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

You want to arrange the numbers $1,2,3, \ldots, 25$ in a sequence with the following property: if $n$ is divisible by $m$, then the $n$th number is divisible by the $m$ th number. How many such sequences are there?

|

24

Let the rearranged numbers be $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{25}$. The number of pairs $(n, m)$ with $n \mid m$ must equal the number of pairs with $a_{n} \mid a_{m}$, but since each pair of the former type is also of the latter type, the converse must be true as well. Thus, $n \mid m$ if and only if $a_{n} \mid a_{m}$. Now for each $n=1,2, \ldots, 6$, the number of values divisible by $n$ uniquely determines $n$, so $n=a_{n}$. Similarly, 7, 8 must either be kept fixed by the rearrangement or interchanged, because they are the only values that divide exactly 2 other numbers in the sequence; since 7 is prime and 8 is not, we conclude they are kept fixed. Then we can easily check by induction that $n=a_{n}$ for all larger composite numbers $n \leq 25$ (by using $m=a_{m}$ for all proper factors $m$ of $n$ ) and $n=11$ (because it is the only prime that divides exactly 1 other number). So we have only the primes $n=13,17,19,23$ left to rearrange, and it is easily seen that these can be permuted arbitrarily, leaving 4 ! possible orderings altogether.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n39. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

885fcc5b-4661-5bfe-a2c7-3222ed016228

| 611,281

|

You would like to provide airline service to the 10 cities in the nation of Schizophrenia, by instituting a certain number of two-way routes between cities. Unfortunately, the government is about to divide Schizophrenia into two warring countries of five cities

each, and you don't know which cities will be in each new country. All airplane service between the two new countries will be discontinued. However, you want to make sure that you set up your routes so that, for any two cities in the same new country, it will be possible to get from one city to the other (without leaving the country).

What is the minimum number of routes you must set up to be assured of doing this, no matter how the government divides up the country?

|

30

Each city $C$ must be directly connected to at least 6 other cities, since otherwise the government could put $C$ in one country and all its connecting cities in the other country, and there would be no way out of $C$. This means that we have 6 routes for each of 10 cities, counted twice (since each route has two endpoints) $\Rightarrow 6 \cdot 10 / 2=30$ routes. On the other hand, this is enough: picture the cities arranged around a circle, and each city connected to its 3 closest neighbors in either direction. Then if $C$ and $D$ are in the same country but mutually inaccessible, this means that on each arc of the circle between $C$ and $D$, there must be (at least) three consecutive cities in the other country. Then this second country would have 6 cities, which is impossible. So our arrangement achieves the goal with 30 routes.

|

30

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

You would like to provide airline service to the 10 cities in the nation of Schizophrenia, by instituting a certain number of two-way routes between cities. Unfortunately, the government is about to divide Schizophrenia into two warring countries of five cities

each, and you don't know which cities will be in each new country. All airplane service between the two new countries will be discontinued. However, you want to make sure that you set up your routes so that, for any two cities in the same new country, it will be possible to get from one city to the other (without leaving the country).

What is the minimum number of routes you must set up to be assured of doing this, no matter how the government divides up the country?

|

30

Each city $C$ must be directly connected to at least 6 other cities, since otherwise the government could put $C$ in one country and all its connecting cities in the other country, and there would be no way out of $C$. This means that we have 6 routes for each of 10 cities, counted twice (since each route has two endpoints) $\Rightarrow 6 \cdot 10 / 2=30$ routes. On the other hand, this is enough: picture the cities arranged around a circle, and each city connected to its 3 closest neighbors in either direction. Then if $C$ and $D$ are in the same country but mutually inaccessible, this means that on each arc of the circle between $C$ and $D$, there must be (at least) three consecutive cities in the other country. Then this second country would have 6 cities, which is impossible. So our arrangement achieves the goal with 30 routes.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n40. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

f0092245-8188-505b-ad8e-e211d5b07978

| 611,282

|

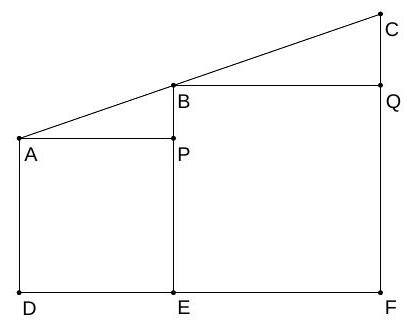

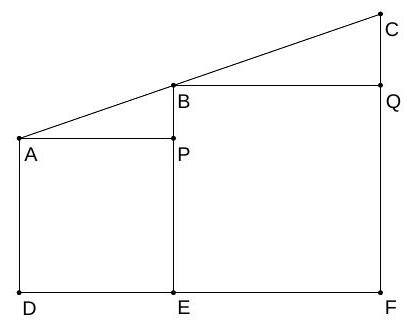

A tetrahedron has all its faces triangles with sides $13,14,15$. What is its volume?

|

$42 \sqrt{55}$

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $A B=13, B C=14, C A=15$. Let $A D, B E$ be altitudes. Then $B D=5, C D=9$. (If you don't already know this, it can be deduced from the Pythagorean Theorem: $C D^{2}-B D^{2}=\left(C D^{2}+A D^{2}\right)-\left(B D^{2}+A D^{2}\right)=A C^{2}-A B^{2}=56$, while $C D+B D=B C=14$, giving $C D-B D=56 / 14=4$, and now solve the linear system.) Also, $A D=\sqrt{A B^{2}-B D^{2}}=12$. Similar reasoning gives $A E=33 / 5$, $E C=42 / 5$.

Now let $F$ be the point on $B C$ such that $C F=B D=5$, and let $G$ be on $A C$ such that $C G=A E=33 / 5$. Imagine placing face $A B C$ flat on the table, and letting $X$ be a point in space with $C X=13, B X=14$. By mentally rotating triangle $B C X$

about line $B C$, we can see that $X$ lies on the plane perpendicular to $B C$ through $F$. In particular, this holds if $X$ is the fourth vertex of our tetrahedron $A B C X$. Similarly, $X$ lies on the plane perpendicular to $A C$ through $G$. Let the mutual intersection of these two planes and plane $A B C$ be $H$. Then $X H$ is the altitude of the tetrahedron.

To find $X H$, extend $F H$ to meet $A C$ at $I$. Then $\triangle C F I \sim \triangle C D A$, a 3-4-5 triangle, so $F I=C F \cdot 4 / 3=20 / 3$, and $C I=C F \cdot 5 / 3=25 / 3$. Then $I G=C I-C G=26 / 15$, and $H I=I G \cdot 5 / 4=13 / 6$. This leads to $H F=F I-H I=9 / 2$, and finally $X H=\sqrt{X F^{2}-H F^{2}}=\sqrt{A D^{2}-H F^{2}}=3 \sqrt{55} / 2$.

Now $X A B C$ is a tetrahedron whose base $\triangle A B C$ has area $A D \cdot B C / 2=12 \cdot 14 / 2=84$, and whose height $X H$ is $3 \sqrt{55} / 2$, so its volume is $(84)(3 \sqrt{55} / 2) / 3=42 \sqrt{55}$.

|

42 \sqrt{55}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A tetrahedron has all its faces triangles with sides $13,14,15$. What is its volume?

|

$42 \sqrt{55}$

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $A B=13, B C=14, C A=15$. Let $A D, B E$ be altitudes. Then $B D=5, C D=9$. (If you don't already know this, it can be deduced from the Pythagorean Theorem: $C D^{2}-B D^{2}=\left(C D^{2}+A D^{2}\right)-\left(B D^{2}+A D^{2}\right)=A C^{2}-A B^{2}=56$, while $C D+B D=B C=14$, giving $C D-B D=56 / 14=4$, and now solve the linear system.) Also, $A D=\sqrt{A B^{2}-B D^{2}}=12$. Similar reasoning gives $A E=33 / 5$, $E C=42 / 5$.

Now let $F$ be the point on $B C$ such that $C F=B D=5$, and let $G$ be on $A C$ such that $C G=A E=33 / 5$. Imagine placing face $A B C$ flat on the table, and letting $X$ be a point in space with $C X=13, B X=14$. By mentally rotating triangle $B C X$

about line $B C$, we can see that $X$ lies on the plane perpendicular to $B C$ through $F$. In particular, this holds if $X$ is the fourth vertex of our tetrahedron $A B C X$. Similarly, $X$ lies on the plane perpendicular to $A C$ through $G$. Let the mutual intersection of these two planes and plane $A B C$ be $H$. Then $X H$ is the altitude of the tetrahedron.

To find $X H$, extend $F H$ to meet $A C$ at $I$. Then $\triangle C F I \sim \triangle C D A$, a 3-4-5 triangle, so $F I=C F \cdot 4 / 3=20 / 3$, and $C I=C F \cdot 5 / 3=25 / 3$. Then $I G=C I-C G=26 / 15$, and $H I=I G \cdot 5 / 4=13 / 6$. This leads to $H F=F I-H I=9 / 2$, and finally $X H=\sqrt{X F^{2}-H F^{2}}=\sqrt{A D^{2}-H F^{2}}=3 \sqrt{55} / 2$.

Now $X A B C$ is a tetrahedron whose base $\triangle A B C$ has area $A D \cdot B C / 2=12 \cdot 14 / 2=84$, and whose height $X H$ is $3 \sqrt{55} / 2$, so its volume is $(84)(3 \sqrt{55} / 2) / 3=42 \sqrt{55}$.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n41. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

639c9937-7056-5e09-9660-1251f59a4cf3

| 611,283

|

$S$ is a set of complex numbers such that if $u, v \in S$, then $u v \in S$ and $u^{2}+v^{2} \in S$. Suppose that the number $N$ of elements of $S$ with absolute value at most 1 is finite. What is the largest possible value of $N$ ?

|

13

First, if $S$ contained some $u \neq 0$ with absolute value $<1$, then (by the first condition) every power of $u$ would be in $S$, and $S$ would contain infinitely many different numbers of absolute value $<1$. This is a contradiction. Now suppose $S$ contains some number $u$ of absolute value 1 and argument $\theta$. If $\theta$ is not an integer multiple of $\pi / 6$, then $u$ has some power $v$ whose argument lies strictly between $\theta+\pi / 3$ and $\theta+\pi / 2$. Then $u^{2}+v^{2}=u^{2}\left(1+(v / u)^{2}\right)$ has absolute value between 0 and 1 , since $(v / u)^{2}$ lies on the unit circle with angle strictly between $2 \pi / 3$ and $\pi$. But $u^{2}+v^{2} \in S$, so this is a contradiction.

This shows that the only possible elements of $S$ with absolute value $\leq 1$ are 0 and the points on the unit circle whose arguments are multiples of $\pi / 6$, giving $N \leq 1+12=13$. To show that $N=13$ is attainable, we need to show that there exists a possible set $S$ containing all these points. Let $T$ be the set of all numbers of the form $a+b \omega$, where $a, b$ are integers are $\omega$ is a complex cube root of 1 . Since $\omega^{2}=-1-\omega, T$ is closed under multiplication and addition. Then, if we let $S$ be the set of numbers $u$ such that $u^{2} \in T, S$ has the required properties, and it contains the 13 complex numbers specified, so we're in business.

|

13

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

$S$ is a set of complex numbers such that if $u, v \in S$, then $u v \in S$ and $u^{2}+v^{2} \in S$. Suppose that the number $N$ of elements of $S$ with absolute value at most 1 is finite. What is the largest possible value of $N$ ?

|

13

First, if $S$ contained some $u \neq 0$ with absolute value $<1$, then (by the first condition) every power of $u$ would be in $S$, and $S$ would contain infinitely many different numbers of absolute value $<1$. This is a contradiction. Now suppose $S$ contains some number $u$ of absolute value 1 and argument $\theta$. If $\theta$ is not an integer multiple of $\pi / 6$, then $u$ has some power $v$ whose argument lies strictly between $\theta+\pi / 3$ and $\theta+\pi / 2$. Then $u^{2}+v^{2}=u^{2}\left(1+(v / u)^{2}\right)$ has absolute value between 0 and 1 , since $(v / u)^{2}$ lies on the unit circle with angle strictly between $2 \pi / 3$ and $\pi$. But $u^{2}+v^{2} \in S$, so this is a contradiction.

This shows that the only possible elements of $S$ with absolute value $\leq 1$ are 0 and the points on the unit circle whose arguments are multiples of $\pi / 6$, giving $N \leq 1+12=13$. To show that $N=13$ is attainable, we need to show that there exists a possible set $S$ containing all these points. Let $T$ be the set of all numbers of the form $a+b \omega$, where $a, b$ are integers are $\omega$ is a complex cube root of 1 . Since $\omega^{2}=-1-\omega, T$ is closed under multiplication and addition. Then, if we let $S$ be the set of numbers $u$ such that $u^{2} \in T, S$ has the required properties, and it contains the 13 complex numbers specified, so we're in business.

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n42. ",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution: "

}

|

eaae2be6-3f12-51a2-80b4-13ef3f55466e

| 611,284

|

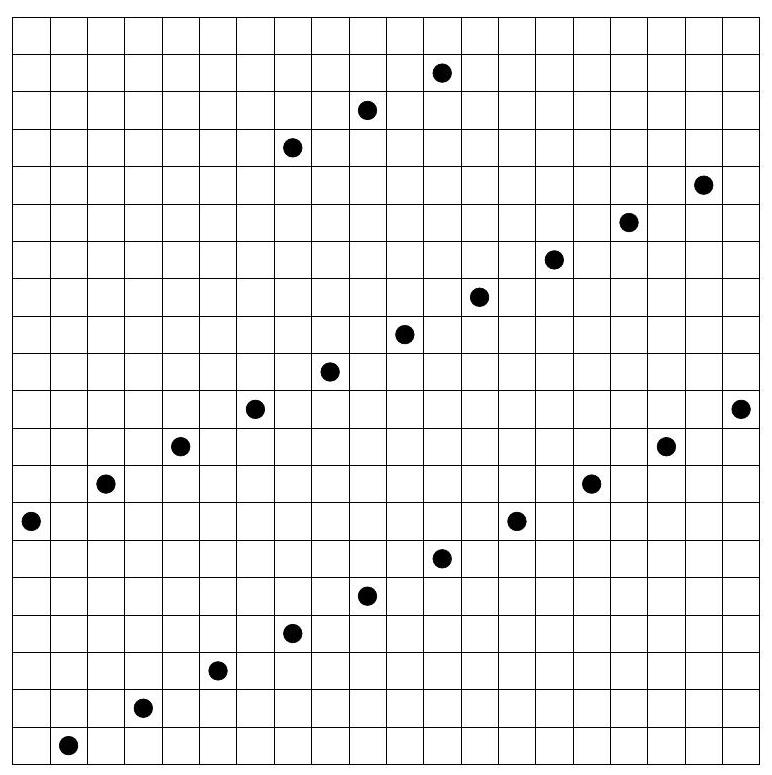

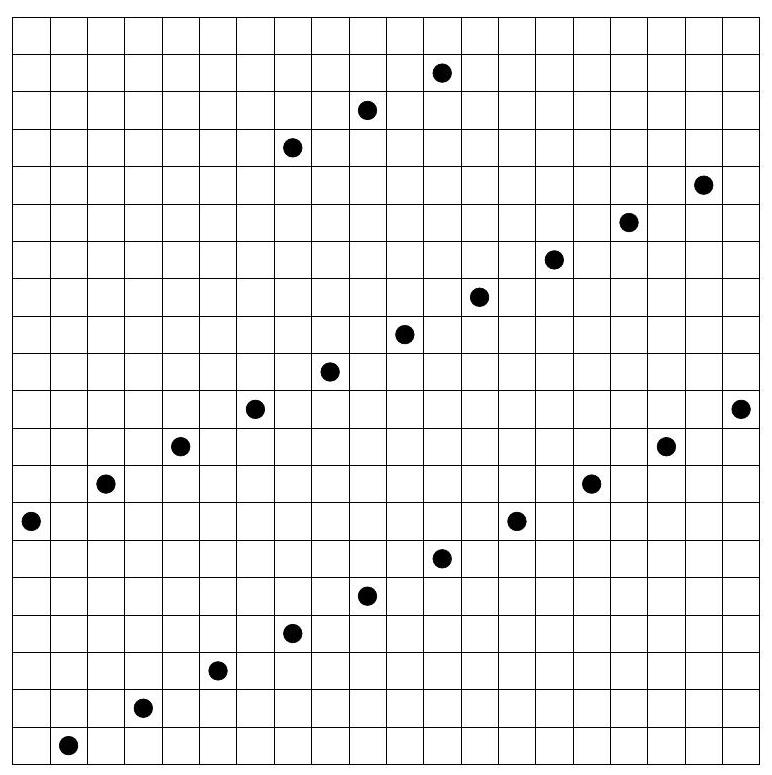

Shown on your answer sheet is a $20 \times 20$ grid. Place as many queens as you can so that each of them attacks at most one other queen. (A queen is a chess piece that can

move any number of squares horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.) It's not very hard to get 20 queens, so you get no points for that, but you get 5 points for each further queen beyond 20 . You can mark the grid by placing a dot in each square that contains a queen.

|

An elementary argument shows there cannot be more than 26 queens: we cannot have more than 2 in a row or column (or else the middle queen would attack the other two), so if we had 27 queens, there would be at least 7 columns with more than one queen and thus at most 13 queens that are alone in their respective columns. Similarly, there would be at most 13 queens that are alone in their respective rows. This leaves $27-13-13=1$ queen who is not alone in her row or column, and she therefore attacks two other queens, contradiction.

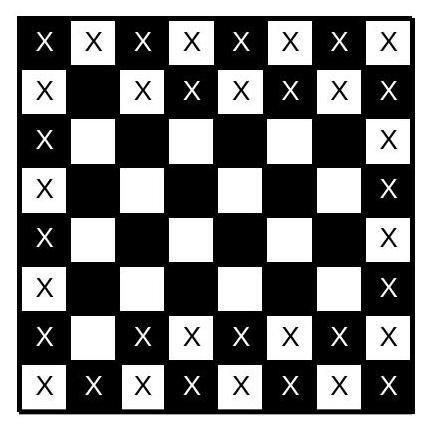

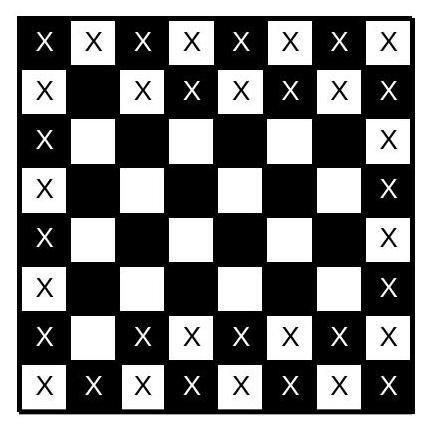

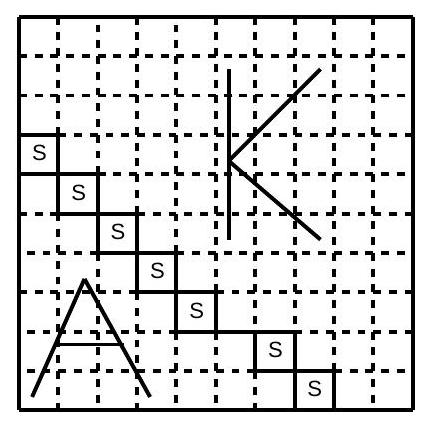

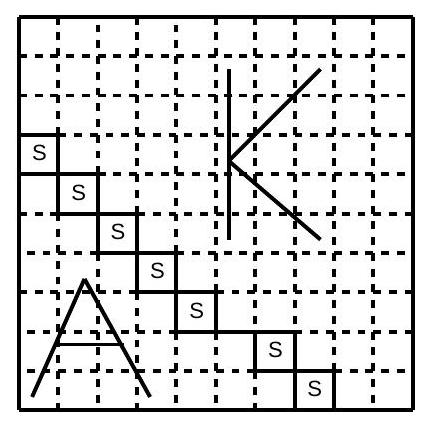

Of course, this is not a very strong argument since it makes no use of the diagonals. The best possible number of queens is not known to us; the following construction gives 23:

|

23

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Shown on your answer sheet is a $20 \times 20$ grid. Place as many queens as you can so that each of them attacks at most one other queen. (A queen is a chess piece that can

move any number of squares horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.) It's not very hard to get 20 queens, so you get no points for that, but you get 5 points for each further queen beyond 20 . You can mark the grid by placing a dot in each square that contains a queen.

|

An elementary argument shows there cannot be more than 26 queens: we cannot have more than 2 in a row or column (or else the middle queen would attack the other two), so if we had 27 queens, there would be at least 7 columns with more than one queen and thus at most 13 queens that are alone in their respective columns. Similarly, there would be at most 13 queens that are alone in their respective rows. This leaves $27-13-13=1$ queen who is not alone in her row or column, and she therefore attacks two other queens, contradiction.

Of course, this is not a very strong argument since it makes no use of the diagonals. The best possible number of queens is not known to us; the following construction gives 23:

|

{

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-72-2004-feb-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"problem_match": "\n44. ",

"solution_match": "\nSolution: "

}

|

79309886-ef5a-5ab4-8952-53a5aadcb69e

| 611,286

|

A binary string of length $n$ is a sequence of $n$ digits, each of which is 0 or 1 . The distance between two binary strings of the same length is the number of positions in which they disagree; for example, the distance between the strings 01101011 and 00101110 is 3 since they differ in the second, sixth, and eighth positions.

Find as many binary strings of length 8 as you can, such that the distance between any two of them is at least 3 . You get one point per string.

|

The maximum possible number of such strings is 20 . An example of a set

attaining this bound is

| 00000000 | 00110101 |